Related Research Articles

Nyaung-u Sawrahan was king of the Pagan dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from c. 956 to 1001. Although he is remembered as the Cucumber King in the Burmese chronicles based on a legend, Sawrahan is the earliest king of Pagan whose existence has been verified by inscriptional evidence. According to scholarship, it was during Sawrahan reign that Pagan, then one of several competing city-states in Upper Burma, "grew in authority and grandeur". The creation of Burmese alphabet as well as the fortification of Pagan may have begun in his reign.

The Battle of Pagan was fought in 1287 between the Yuan dynasty of China and the Pagan Kingdom of Burma. The invasion ended the Pagan Kingdom, which disintegrated into several small kingdoms.

Narathihapate was the last king of the Pagan Empire who reigned from 1256 to 1287. The king is known in Burmese history as the "Taruk-Pyay Min" for his flight from Pagan (Bagan) to Lower Burma in 1285 during the first Mongol invasion (1277–87) of the kingdom. He eventually submitted to Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty in January 1287 in exchange for a Mongol withdrawal from northern Burma. But when the king was assassinated six months later by his son Thihathu, the Viceroy of Prome, the 250-year-old Pagan Empire broke apart into multiple petty states. The political fragmentation of the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery would last for another 250 years until the mid-16th century.

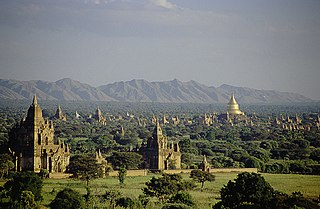

Arimardanna Pura is the most famous classical name of the city of Bagan (Pagan), Myanmar. It means the "City that Tramples on Enemies."

Narapati Sithu was king of Pagan dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1174 to 1211. He is considered the last important king of Pagan. His peaceful and prosperous reign gave rise to Burmese culture which finally emerged from the shadows of Mon and Pyu cultures. The Burman leadership of the kingdom was now unquestioned. The Pagan Empire reached its peak during his reign, and would decline gradually after his death.

Taninganway Min was king of the Toungoo dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1714 to 1733. The long and slow descent of the dynasty finally came to the forefront during his reign in the form of internal and external instabilities. He faced a rebellion by his uncle Governor of Pagan at his accession. In the northwest, the Manipuri horsemen raided Burmese territory in early 1724. The retaliatory expedition to Manipur in November 1724 failed. In the east, southern Lan Na, under Burmese rule since 1558, successfully revolted in 1727. Taninganway tried to recapture the breakaway region twice but both tries failed. By 1732, southern Lan Na was independent although a strong Burmese garrison in Chiang Saen in northern Lan Na confined the rebellion to the Ping valley around Chiang Mai.

Htilominlo was king of the Pagan dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1211 to 1235. His 24-year reign marked the beginning of the gradual decline of Pagan dynasty. It was the first to see the impact of over a century of continuous growth of tax-free religious wealth, which had greatly reduced the potential tax base. Htilominlo was the last of the temple builders although most of his temples were in remote lands outside the Pagan region, reflecting the deteriorating state of royal treasury.

Kunhsaw Kyaunghpyu was king of the Pagan Dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) from 1001 to 1021. He was the father of Anawrahta, the founder of Pagan Empire. The principality of Pagan continued to gain strength during his reign. Pagan's surviving walls were most likely constructed during his reign.

Pyinbya was the king of the Pagan Dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) who founded the city of Pagan (Bagan) in 849 CE. Though the Burmese chronicles describe him as the 33rd king of the dynasty founded in early 2nd century CE, modern historians consider Pyinbya one of the first kings of Pagan, which would gradually take over present-day central Burma in the next two hundred years. He was the paternal great-grandfather of King Anawrahta, the founder of the Pagan Empire.

The royal chronicles of Myanmar are detailed and continuous chronicles of the monarchy of Myanmar (Burma). The chronicles were written on different media such as parabaik paper, palm leaf, and stone; they were composed in different literary styles such as prose, verse, and chronograms. Palm-leaf manuscripts written in prose are those that are commonly referred to as the chronicles. Other royal records include administrative treatises and precedents, legal treatises and precedents, and censuses.

Hmannan Maha Yazawindawgyi is the first official chronicle of Konbaung Dynasty of Burma (Myanmar). It was compiled by the Royal Historical Commission between 1829 and 1832. The compilation was based on several existing chronicles and local histories, and the inscriptions collected on the orders of King Bodawpaya, as well as several types of poetry describing epics of kings. Although the compilers disputed some of the earlier accounts, they by and large retained the accounts given Maha Yazawin, the standard chronicle of Toungoo Dynasty.

Maha Yazawin Thit is a national chronicle of Burma (Myanmar). Completed in 1798, the chronicle was the first attempt by the Konbaung court to update and check the accuracy of Maha Yazawin, the standard chronicle of the previous Toungoo Dynasty. Its author Twinthin Taikwun Maha Sithu consulted several existing written sources, and over 600 stone inscriptions collected from around the kingdom between 1783 and 1793. It is the first historical document in Southeast Asia compiled in consultation with epigraphic evidence.

The Maha Yazawin, fully the Maha Yazawindawgyi and formerly romanized as the Maha-Radza Weng, is the first national chronicle of Burma/Myanmar. Completed in 1724 by U Kala, a historian at the Toungoo court, it was the first chronicle to synthesize all the ancient, regional, foreign and biographic histories related to Burmese history. Prior to the chronicle, the only known Burmese histories were biographies and comparatively brief local chronicles. The chronicle has formed the basis for all subsequent histories of the country, including the earliest English language histories of Burma written in the late 19th century.

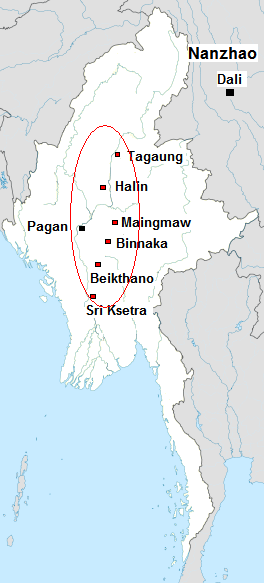

The Early Pagan Kingdom was a city-state that existed in the first millennium CE before the emergence of the Pagan Empire in the mid 11th century. The Burmese chronicles state that the "kingdom" was founded in the second century CE. The seat of power of the small kingdom was first located at Arimaddana, Thiri Pyissaya, and Tampawaddy until 849 CE when it was moved to Pagan (Bagan).

Pagan Yazawin (Burmese: ပုဂံ ရာဇဝင်; also known as Pagan Yazawin Haung is a 16th-century Burmese chronicle that covers the history of the Pagan Dynasty. One palm-leaf manuscript copy of the chronicle is stored at the Universities Historical Research Center in Yangon.

These are the lists related to the Family of Emperor Bayinnaung of the Toungoo Dynasty of Burma. The king had over 50 wives and nearly 100 children. All the Toungoo monarchs after him were descended from him.

The Mani Yadanabon is an 18th-century court treatise on Burmese statecraft and court organization. The text is a compilation of exemplary "advice offered by various ministers to Burmese sovereigns from the late 14th to the early 18th century." It is "a repository of historical examples illustrating pragmatic political principles worthy of Machiavelli".

References

- ↑ Seekins, Donald M. (2006). Historical Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar). Scarecrow Press. p. 270. ISBN 9780810854765.

- ↑ Hla Pe (1985). Burma: Literature, Historiography, Scholarship, Language, Life, and Buddhism. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 38–40. ISBN 9789971988005.

- ↑ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780521800860.

- 1 2 Myint-U, Thant (2001). The Making of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780521799140.

- 1 2 3 Lieberman, Victor (1986-01-01). "How Reliable Is U Kala's Burmese Chronicle? Some New Comparisons". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 17 (2): 236–255. doi:10.1017/s002246340000103x. JSTOR 20070918.