Related Research Articles

United States v. Schooner Amistad, 40 U.S. 518 (1841), was a United States Supreme Court case resulting from the rebellion of Africans on board the Spanish schooner La Amistad in 1839. It was an unusual freedom suit that involved international diplomacy as well as United States law. The historian Samuel Eliot Morison described it in 1969 as the most important court case involving slavery before being eclipsed by that of Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857.

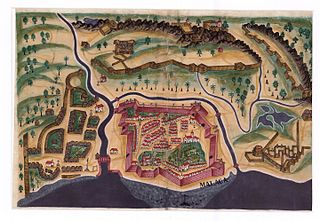

The Malacca Sultanate was a Malay sultanate based in the modern-day state of Malacca, Malaysia. Conventional historical thesis marks c. 1400 as the founding year of the sultanate by King of Singapura, Parameswara, also known as Iskandar Shah, although earlier dates for its founding have been proposed. At the height of the sultanate's power in the 15th century, its capital grew into one of the most important transshipment ports of its time, with territory covering much of the Malay Peninsula, the Riau Islands and a significant portion of the northern coast of Sumatra in present-day Indonesia.

The Indonesian Navy is the naval branch of the Indonesian National Armed Forces. It was founded on 10 September 1945 and has a role to patrol Indonesia's lengthy coastline, to enforce and patrol the territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Indonesia, to protect Indonesia's maritime strategic interests, to protect the islands surrounding Indonesia, and to defend against seaborne threats.

Malaysian legal history has been determined by events spanning a period of some six hundred years. Of these, three major periods were largely responsible for shaping the current Malaysian system. The first was the founding of the Melaka Sultanate at the beginning of the 15th century; second was the spread of Islam in the indigenous culture; and finally, and perhaps the most significant in modern Malaysia, was British colonial rule which brought with it constitutional government and the common law system.

A charterparty is a maritime contract between a shipowner and a "charterer" for the hire of either a ship for the carriage of passengers or cargo, or a yacht for leisure.

A sea captain, ship's captain, captain, master, or shipmaster, is a high-grade licensed mariner who holds ultimate command and responsibility of a merchant vessel. The captain is responsible for the safe and efficient operation of the ship, including its seaworthiness, safety and security, cargo operations, navigation, crew management, and legal compliance, and for the persons and cargo on board.

The Yamtuan Besar, also known officially as Yang di-Pertuan Besar and unofficially as Grand Ruler, is the royal title of the ruler of the Malaysian state of Negeri Sembilan. The Grand Ruler of Negeri Sembilan is elected by a council of ruling chiefs in the state, or the Undangs. This royal practice has been followed since 1773. The Yamtuan Besar is elected from among the four leading princes of Negeri Sembilan ; the Undangs themselves cannot stand for election and their choice of a ruler is limited to a male Muslim who is Malay and also a "lawfully begotten descendant of Raja Radin ibni Raja Lenggang", the 4th Yamtuan.

Iskandar Muda was the twelfth Sultan of Acèh Darussalam, under whom the sultanate achieved its greatest territorial extent, holding sway as the strongest power and wealthiest state in the western Indonesian archipelago and the Strait of Malacca. "Iskandar Muda" literally means "young Alexander," and his conquests were often compared to those of Alexander the Great. In addition to his notable conquests, during his reign, Aceh became known as an international centre of Islamic learning and trade. He was the last Sultan of Aceh who was a direct lineal male descendant of Ali Mughayat Syah, the founder of the Aceh Sultanate. Iskandar Muda's death meant that the founding dynasty of the Aceh Sultanate, the House of Meukuta Alam died out and was replaced by another dynasty.

The Articles of War are a set of regulations drawn up to govern the conduct of a country's military and naval forces. The first known usage of the phrase is in Robert Monro's 1637 work His expedition with the worthy Scot's regiment called Mac-keyes regiment etc. and can be used to refer to military law in general. In Swedish, the equivalent term Krigsartiklar, is first mentioned in 1556. However, the term is usually used more specifically and with the modern spelling and capitalisation to refer to the British regulations drawn up in the wake of the Glorious Revolution and the United States regulations later based on them.

Affreightment is a legal term relating to shipping.

The Mongolian nationality law is a nationality law that determines who is a citizen of Mongolia.

The doctrine of deviation is a particular aspect of contracts of carriage of goods by sea. A deviation is a departure from the "agreed route" or the "usual route", and it can amount to a serious breach of contract.

The Battle of Duyon River was a naval engagement between the Portuguese forces commanded by Nuno Álvares Botelho, who is renowned in Portugal as one of the last great commanders of Portuguese India, and the forces of the Sultanate of Aceh, which were led by the Laksamana.

The Marshall Court (1801–1835) heard forty-one criminal law cases, slightly more than one per year. Among such cases are United States v. Simms (1803), United States v. More (1805), Ex parte Bollman (1807), United States v. Hudson (1812), Cohens v. Virginia (1821), United States v. Perez (1824), Worcester v. Georgia (1832), and United States v. Wilson (1833).

In keeping with the Paris Principles definition of a child soldier, the Roméo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative defines a child pirate as any person below 18 years of age who is or who has been recruited or used by a pirate gang in any capacity, including children – boys and/or girls – used as gunmen in boarding parties, hostage guards, negotiators, ship captains, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes, whether at sea or on land. It does not only refer to a child who is taking or has taken a direct part in kinetic criminal operations.

Sultan Abdul Ghafur Muhiuddin Shah ibni Almarhum Sultan Abdul Kadir Alauddin Shah was the 12th Sultan of Pahang reigning from 1592 to 1614. He was originally appointed as regent for his younger half-brother of a royal mother, Ahmad Shah II after the death of their father, Sultan Abdul Kadir Alauddin Shah in 1590. Two years later he deposed his half-brother and assumed power.

The Pahang Sultanate also referred as the Old Pahang Sultanate, as opposed to the modern Pahang Sultanate, was a Malay Muslim state established in the eastern Malay Peninsula in the 15th century. At the height of its influence, the sultanate was an important power in Southeast Asia and controlled the entire Pahang basin, bordering the Pattani Sultanate to the north and the Johor Sultanate to the south. To the west, its jurisdiction extended over parts of modern-day Selangor and Negeri Sembilan.

The Indonesian Sea and Coast Guard Unit is an agency of Government of Indonesia which main function is to ensure the safety of shipping inside the Indonesian Maritime Zone. KPLP has the task of formulating and execute policies, standards, norms, guidelines, criteria and procedures, as well as technical guidance, evaluation and reporting on patrol and security, safety monitoring and Civil Service Investigator (PPNS), order of shipping, water, facilities and infrastructure of coastal and marine guarding. KPLP is under the Directorate General of Sea Transportation of the Indonesian Ministry of Transportation. Therefore, KPLP reports directly to the Minister of Transportation of the Republic of Indonesia. KPLP is not associated or part of the Indonesian National Armed Forces. KPLP, however often conduct joint-exercise and joint-operations with the Indonesian Navy.

A kakap is a narrow river or coastal boat used for fishing in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei. They are also sometimes used as auxiliary vessels to larger warships for piracy and coastal raids.

The Minangkabau Malaysians are citizens of the Malaysia whose ancestral roots are from Minangkabau of central Sumatra. This includes people born in the Malaysia who are of Minangkabau origin as well as Minangkabau who have migrated to Malaysia. Today, Minangkabau comprise about 989,000 people in Malaysia, and Malaysian law considers most of them to be Malays. They are majority in urban areas, which has traditionally had the highest education and a strong entrepreneurial spirit. The history of the Minangkabau migration to Malay peninsula has been recorded to have lasted a very long time. When the means of transportation were still using the ships by down the rivers and crossing the strait, many Minang people migrated to various regions such as Negeri Sembilan, Malacca, Penang, Kedah, Perak, and Pahang. Some scholars noted that the arrival of the Minangkabau to the Malay Peninsula occurred in the 12th century. This ethnic group moved in to peninsula at the height of the Sultanate of Malacca, and maintains the Adat Perpatih of matrilineal kinships system in Negeri Sembilan and north Malacca.

References

- ↑ Reid 1993, p. 39.

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 18

- ↑ Ahmad Sarji Abdul Hamid 2011 , p. 115

- ↑ Reddie 1841, p. 484

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , pp. 482–483

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 482

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 482

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 19

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 19

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 17

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 17

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 17

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 17

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , pp. 16&19

- ↑ Tarling 2000 , p. 133

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 18

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , pp. 16&18

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , pp. 485–486

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , pp. 17&18

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 483

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 483

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 17

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 17

- ↑ Tarling 2000 , p. 133

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , pp. 17&18

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 486

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 483

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 16

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 487

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 16

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , pp. 16&20

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 16

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , p. 16

- ↑ Mardiana Nordin 2008 , pp. 17

- ↑ Reddie 1841 , p. 483