Alfonso III, called the Liberal and the Free, was king of Aragon and Valencia, and count of Barcelona from 1285 until his death. He conquered the Kingdom of Majorca between his succession and 1287.

James I the Conqueror was King of Aragon and Lord of Montpellier from 1213 to 1276; King of Majorca from 1231 to 1276; and Valencia from 1238 to 1276 and Count of Barcelona. His long reign of 62 years is not only the longest of any Iberian monarch, but one of the longest monarchical reigns in history, ahead of Hirohito but remaining behind Queen Victoria and Ferdinand III of Naples and Sicily. He saw the expansion of the Crown of Aragon in three directions: Languedoc to the north, the Balearic Islands to the southeast, and Valencia to the south. By a treaty with Louis IX of France, he achieved the renunciation of any possible claim of French suzerainty over the County of Barcelona and the other Catalan counties, while he renounced northward expansion and taking back the once Catalan territories in Occitania and vassal counties loyal to the County of Barcelona, lands that were lost by his father Peter II of Aragon in the Battle of Muret during the Albigensian Crusade and annexed by the Kingdom of France, and then decided to turn south. His great part in the Reconquista was similar in Mediterranean Spain to that of his contemporary Ferdinand III of Castile in Andalusia. One of the main reasons for this formal renunciation of most of the once Catalan territories in Languedoc and Occitania and any expansion into them is the fact that he was raised by the Knights Templar crusaders, who had defeated his father fighting for the Pope alongside the French, so it was effectively forbidden for him to try to maintain the traditional influence of the Count of Barcelona that previously existed in Occitania and Languedoc.

Peter III of Aragon was King of Aragon, King of Valencia, and Count of Barcelona from 1276 to his death. At the invitation of some rebels, he conquered the Kingdom of Sicily and became King of Sicily in 1282, pressing the claim of his wife, Constance II of Sicily, uniting the kingdom to the crown.

Philip III, called the Bold, was King of France from 1270 until his death in 1285. His father, Louis IX, died in Tunis during the Eighth Crusade. Philip, who was accompanying him, returned to France and was anointed king at Reims in 1271.

Peter I was King of Aragon and also Pamplona from 1094 until his death in 1104. Peter was the eldest son of Sancho Ramírez, from whom he inherited the crowns of Aragon and Pamplona, and Isabella of Urgell. He was named in honour of Saint Peter, because of his father's special devotion to the Holy See, to which he had made his kingdom a vassal. Peter continued his father's close alliance with the Church and pursued his military thrust south against bordering Al-Andalus taifas with great success, allying with Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, known as El Cid, the ruler of Valencia, against the Almoravids. According to the medieval Annales Compostellani Peter was "expert in war and daring in initiative", and one modern historian has remarked that "his grasp of the possibilities inherent in the age seems to have been faultless."

Ramiro II, called the Monk, was a member of the House of Jiménez who became king of Aragon in 1134. Although a monk, he was elected by the Aragonese nobility to succeed his childless brother Alfonso the Battler. He then had a daughter, Petronilla, whom he had marry Count Ramon Berenguer IV of Barcelona, unifying Aragon and Barcelona into the Crown of Aragon. He withdrew to a monastery in 1137, leaving authority to Ramon Berenguer but keeping the royal title until his death.

Peter IV, called the Ceremonious, was from 1336 until his death the king of Aragon, Sardinia-Corsica, and Valencia, and count of Barcelona. In 1344, he deposed James III of Majorca and made himself King of Majorca.

John I, called by posterity the Hunter or the Lover of Elegance, or the Abandoned in his lifetime, was the King of Aragon from 1387 until his death.

The Kingdom of Aragon was a medieval and early modern kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon, in Spain. It should not be confused with the larger Crown of Aragon, which also included other territories—the Principality of Catalonia, the Kingdom of Valencia, the Kingdom of Majorca, and other possessions that are now part of France, Italy, and Greece—that were also under the rule of the King of Aragon, but were administered separately from the Kingdom of Aragon.

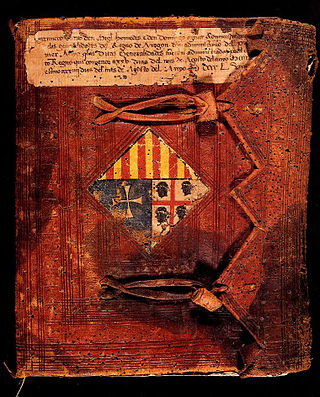

The Crown of Aragon was a composite monarchy ruled by one king, originated by the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Aragon and the County of Barcelona and ended as a consequence of the War of the Spanish Succession. At the height of its power in the 14th and 15th centuries, the Crown of Aragon was a thalassocracy controlling a large portion of present-day eastern Spain, parts of what is now southern France, and a Mediterranean empire which included the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, Malta, Southern Italy and parts of Greece.

Spain in the Middle Ages is a period in the History of Spain that began in the 5th Century following the Fall of the Western Roman Empire and ended with the beginning of the Early modern period in 1492.

The 1412 Compromise of Caspe was an act and resolution of parliamentary representatives of the constituent realms of the Crown of Aragon, meeting in Caspe, to resolve the interregnum following the death of King Martin of Aragon in 1410 without a legitimate heir.

The Aragonese Crusade (1284–1285), also known as the Crusade of Aragon, was a military venture waged by the Kingdom of France against the Crown of Aragon. Fought as an extension of the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302), the crusade was called by Pope Martin IV in retribution for Peter III of Aragon's intervention in Sicily, which had damaged the political ambitions of the papacy and France.

The War of the Sicilian Vespers, also shortened to the War of the Vespers, was a conflict waged by several medieval European kingdoms over control of Sicily from 1282 to 1302. The war, which started with the revolt of the Sicilian Vespers, was fought over competing dynastic claims to the throne of Sicily and grew to involve the Kingdom of Aragon, Angevin Kingdom of Naples, Kingdom of France, and the papacy.

The Catalan Civil War, also called the Catalonian Civil War or the War against John II, was a civil war in the Principality of Catalonia, then part of the Crown of Aragon, between 1462 and 1472. The two factions, the royalists who supported John II of Aragon and the Catalan constitutionalists, disputed the extent of royal rights in Catalonia. The French entered the war at times on the side on John II and at times with the Catalans. The Catalans, who at first rallied around John's son Charles of Viana, set up several pretenders in opposition to John during the course of the conflict. Barcelona remained their stronghold to the end: with its surrender the war came to a close. John, victorious, re-established the status quo ante bellum.

The Union of Valencia was an anti-royalist movement in the Kingdom of Valencia begun in 1283 and lasting into the fifteenth century. The Union was formed in the aftermath of the formation of the Union of Aragon in October 1283. Its essential purpose was as a tool of the Valencian nobility to be used against the influence of Catalans and foreigners on the actions of the Crown. By 1285 the Unions had severely curtailed the powers of the king and were hindering his efforts in the War of the Sicilian Vespers and against the Aragonese Crusade that invaded Catalonia that year.

The Battle of Épila was fought on July 21, 1348, near Zaragoza, in what is now Spain, between the supporters of the Union of Aragon and King Peter IV, led by Don Lope de Luna. This battle was the culmination of a long confrontation between a large segment of the nobility and the people of Aragon against the king, ending with the decisive defeat of the Union.

Fernando Sánchez de Castro (1241–1275) was an Aragonese infante, crusader and rebel leader.

The Diputación del General del Reino de Aragón, Diputación del Reino de Aragón or Generalidad de Aragón was an Aragonese institution in force between 1364 and 1708 whose function was the representation by the estates of the realm of the Kingdom of Aragon in periods between Cortes before the King of Aragon and the rest of the peninsular kingdoms. It was in charge of intervening in internal and external fiscal, administrative and political affairs and of safeguarding and ensuring compliance with the aragonese Fueros.