Related Research Articles

Hill v Church of Scientology of Toronto February 20, 1995 – July 20, 1995. 2 S.C.R. 1130 was a libel case against the Church of Scientology, in which the Supreme Court of Canada interpreted Ontario's libel law in relation to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that U.S. state laws criminalizing sodomy between consenting adults are unconstitutional. The Court reaffirmed the concept of a "right to privacy" that earlier cases had found the U.S. Constitution provides, even though it is not explicitly enumerated. It based its ruling on the notions of personal autonomy to define one's own relationships and of American traditions of non-interference with any or all forms of private sexual activities between consenting adults.

Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld, in a 5–4 ruling, the constitutionality of a Georgia sodomy law criminalizing oral and anal sex in private between consenting adults, in this case with respect to homosexual sodomy, though the law did not differentiate between homosexual and heterosexual sodomy. It was overturned in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), though the statute had already been struck down by the Georgia Supreme Court in 1998.

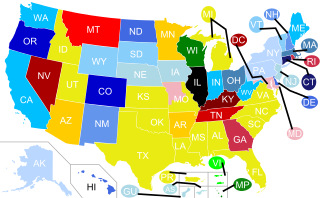

The United States has inherited sodomy laws which constitutionally outlawed a variety of sexual acts that are deemed to be illegal, illicit, unlawful, unnatural or immoral from the colonial-era based laws in the 17th century. While they often targeted sexual acts between persons of the same sex, many sodomy-related statutes employed definitions broad enough to outlaw certain sexual acts between persons of different sexes, in some cases even including acts between married persons.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces is an Article I court that exercises worldwide appellate jurisdiction over members of the United States Armed Forces on active duty and other persons subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice. The court is composed of five civilian judges appointed for 15-year terms by the president of the United States with the advice and consent of the United States Senate. The court reviews decisions from the intermediate appellate courts of the services: the Army Court of Criminal Appeals, the Navy-Marine Corps Court of Criminal Appeals, the Coast Guard Court of Criminal Appeals, and the Air Force Court of Criminal Appeals.

United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1 (1953), is a landmark legal case decided in 1953, which saw the formal recognition of the state secrets privilege, a judicially recognized extension of presidential power. The US Supreme Court confirmed that "the privilege against revealing military secrets ... is well established in the law of evidence".

An Article 32 hearing is a proceeding under the United States Uniform Code of Military Justice, similar to that of a preliminary hearing in civilian law. Its name is derived from UCMJ section VII Article 32, which mandates the hearing.

Courts-martial of the United States are trials conducted by the U.S. military or by state militaries. Most commonly, courts-martial are convened to try members of the U.S. military for violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). They can also be convened for other purposes, including military tribunals and the enforcement of martial law in an occupied territory. Federal courts-martial are governed by the rules of procedure and evidence laid out in the Manual for Courts-Martial, which contains the Rules for Courts-Martial (RCM), Military Rules of Evidence, and other guidance. State courts-martial are governed according to the laws of the state concerned. The American Bar Association has issued a Model State Code of Military Justice, which has influenced the relevant laws and procedures in some states.

The Navy-Marine Corps Court of Criminal Appeals (NMCCA) is the intermediate appellate court for criminal convictions in the United States Navy and the Marine Corps.

In the United States military, the Army Court of Criminal Appeals (ACCA) is an appellate court that reviews certain court martial convictions of Army personnel.

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984), was a landmark Supreme Court case that established the standard for determining when a criminal defendant's Sixth Amendment right to counsel is violated by that counsel's inadequate performance.

The Supreme Court of the United States handed down nineteen per curiam opinions during its 2009 term, which began on October 5, 2009, and concluded October 3, 2010.

Baker v. Wade 563 F.Supp 1121, rev'd 769 F.2nd 289 cert denied 478 US 1022 (1986) is a federal lawsuit challenging the legality of the sodomy law of the state of Texas. Plaintiff Donald Baker contended that the law violated his rights to privacy and equal protection. After a victory at trial, an appellate court reversed the lower court's decision and in the wake of its decision in Bowers v. Hardwick the Supreme Court of the United States refused to review it.

Cook v. Gates, 528 F.3d 42, is a decision on July 9, 2008, of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit that upheld the "Don't ask, Don't tell" (DADT) policy against due process and equal protection Fifth Amendment challenges and a free speech challenge under the First Amendment, and which found that no earlier Supreme Court decision held that sexual orientation is a suspect or quasi-suspect classification.

Lofton v. Secretary of the Department of Children & Family Services, is a 2004 decision from the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit upholding Florida's ban of adoption of children by homosexual persons as enforced by the Florida Department of Children and Families.

The Judge Advocate General's Corps is the military justice branch or specialty of the United States Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marine Corps, and Navy. Officers serving in the JAG Corps are typically called judge advocates.

State v Quattlebaum is a 2000 decision of the South Carolina Supreme Court. The case is notable for having established the precedent that a defendant may, with restrictions, call the prosecuting attorney as a witness.

Unlawful command influence (UCI) is a legal concept within American military law. UCI occurs when a person bearing "the mantle of command authority" uses or appears to use that authority to influence the outcome of military judicial proceedings. Military commanders typically exert significant control over their units, but under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) a commander must take a detached, quasi-judicial stance towards certain disciplinary proceedings such as a court-martial. Outside of certain formal actions authorized by the UCMJ, a commander using their authority to influence the outcome of a court-martial commits UCI. If UCI has occurred, the results of a court-martial may be legally challenged and in some cases overturned.

Section 839(a) of title 10 United States Code § 925 - Article 125. is a punitive article of the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

Doe v. Commonwealth's Attorney of Richmond, 425 U.S. 901 (1976), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States which gave summary affirmation of a lower court ruling which upheld the U.S. state of Virginia's ban on homosexual sodomy.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 United States v. Marcum, 60M.J.198 (C.A.A.F.2004). via armfor.uscourts.gov

- ↑ United States v. Marcum,No. ACM 34216, slip op.(A.F. Ct. Crim. App.July 25, 2002).

- ↑ Lawrence v. Texas , 539U.S.558, 123 S.Ct. 2472 (2003). via law.cornell.edu

- ↑ Janofsky, Michael (August 24, 2004). "In Limited Ruling, Court Upholds Military Ban on Sodomy". The New York Times . Retrieved July 12, 2011.