In mathematical physics and mathematics, the Pauli matrices are a set of three 2 × 2 complex matrices that are traceless, Hermitian, involutory and unitary. Usually indicated by the Greek letter sigma, they are occasionally denoted by tau when used in connection with isospin symmetries.

The stress–energy tensor, sometimes called the stress–energy–momentum tensor or the energy–momentum tensor, is a tensor physical quantity that describes the density and flux of energy and momentum in spacetime, generalizing the stress tensor of Newtonian physics. It is an attribute of matter, radiation, and non-gravitational force fields. This density and flux of energy and momentum are the sources of the gravitational field in the Einstein field equations of general relativity, just as mass density is the source of such a field in Newtonian gravity.

In statistics, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is a method of estimating the parameters of an assumed probability distribution, given some observed data. This is achieved by maximizing a likelihood function so that, under the assumed statistical model, the observed data is most probable. The point in the parameter space that maximizes the likelihood function is called the maximum likelihood estimate. The logic of maximum likelihood is both intuitive and flexible, and as such the method has become a dominant means of statistical inference.

In particle physics, the Georgi–Glashow model is a particular Grand Unified Theory (GUT) proposed by Howard Georgi and Sheldon Glashow in 1974. In this model, the Standard Model gauge groups SU(3) × SU(2) × U(1) are combined into a single simple gauge group SU(5). The unified group SU(5) is then thought to be spontaneously broken into the Standard Model subgroup below a very high energy scale called the grand unification scale.

A Newtonian fluid is a fluid in which the viscous stresses arising from its flow are at every point linearly correlated to the local strain rate — the rate of change of its deformation over time. Stresses are proportional to the rate of change of the fluid's velocity vector.

Projectile motion is a form of motion experienced by an object or particle that is projected in a gravitational field, such as from Earth's surface, and moves along a curved path under the action of gravity only. In the particular case of projectile motion on Earth, most calculations assume the effects of air resistance are passive.

In physics, the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, named after William Rowan Hamilton and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi, is an alternative formulation of classical mechanics, equivalent to other formulations such as Newton's laws of motion, Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics.

In physics, the Polyakov action is an action of the two-dimensional conformal field theory describing the worldsheet of a string in string theory. It was introduced by Stanley Deser and Bruno Zumino and independently by L. Brink, P. Di Vecchia and P. S. Howe in 1976, and has become associated with Alexander Polyakov after he made use of it in quantizing the string in 1981. The action reads:

In probability theory and statistics, the generalized extreme value (GEV) distribution is a family of continuous probability distributions developed within extreme value theory to combine the Gumbel, Fréchet and Weibull families also known as type I, II and III extreme value distributions. By the extreme value theorem the GEV distribution is the only possible limit distribution of properly normalized maxima of a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables. Note that a limit distribution needs to exist, which requires regularity conditions on the tail of the distribution. Despite this, the GEV distribution is often used as an approximation to model the maxima of long (finite) sequences of random variables.

In differential geometry, the four-gradient is the four-vector analogue of the gradient from vector calculus.

In theoretical physics, massive gravity is a theory of gravity that modifies general relativity by endowing the graviton with a nonzero mass. In the classical theory, this means that gravitational waves obey a massive wave equation and hence travel at speeds below the speed of light.

A theoretical motivation for general relativity, including the motivation for the geodesic equation and the Einstein field equation, can be obtained from special relativity by examining the dynamics of particles in circular orbits about the Earth. A key advantage in examining circular orbits is that it is possible to know the solution of the Einstein Field Equation a priori. This provides a means to inform and verify the formalism.

The telegrapher's equations are a set of two coupled, linear equations that predict the voltage and current distributions on a linear electrical transmission line. The equations are important because they allow transmission lines to be analyzed using circuit theory. The equations and their solutions are applicable from 0 Hz to frequencies at which the transmission line structure can support higher order non-TEM modes. The equations can be expressed in both the time domain and the frequency domain. In the time domain the independent variables are distance and time. The resulting time domain equations are partial differential equations of both time and distance. In the frequency domain the independent variables are distance and either frequency, , or complex frequency, . The frequency domain variables can be taken as the Laplace transform or Fourier transform of the time domain variables or they can be taken to be phasors. The resulting frequency domain equations are ordinary differential equations of distance. An advantage of the frequency domain approach is that differential operators in the time domain become algebraic operations in frequency domain.

In statistics, the multivariate t-distribution is a multivariate probability distribution. It is a generalization to random vectors of the Student's t-distribution, which is a distribution applicable to univariate random variables. While the case of a random matrix could be treated within this structure, the matrix t-distribution is distinct and makes particular use of the matrix structure.

A ratio distribution is a probability distribution constructed as the distribution of the ratio of random variables having two other known distributions. Given two random variables X and Y, the distribution of the random variable Z that is formed as the ratio Z = X/Y is a ratio distribution.

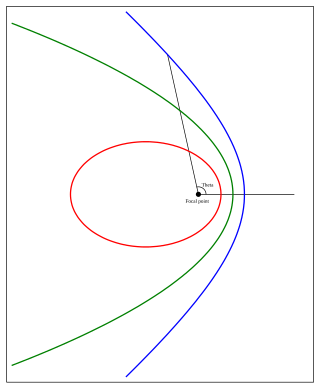

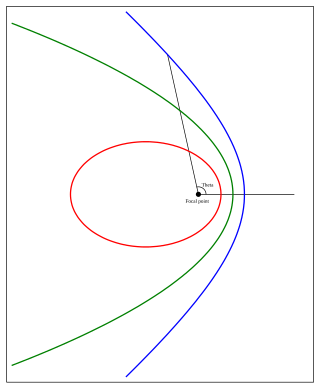

In celestial mechanics, a Kepler orbit is the motion of one body relative to another, as an ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola, which forms a two-dimensional orbital plane in three-dimensional space. A Kepler orbit can also form a straight line. It considers only the point-like gravitational attraction of two bodies, neglecting perturbations due to gravitational interactions with other objects, atmospheric drag, solar radiation pressure, a non-spherical central body, and so on. It is thus said to be a solution of a special case of the two-body problem, known as the Kepler problem. As a theory in classical mechanics, it also does not take into account the effects of general relativity. Keplerian orbits can be parametrized into six orbital elements in various ways.

In classical mechanics, the Udwadia–Kalaba formulation is a method for deriving the equations of motion of a constrained mechanical system. The method was first described by Anatolii Fedorovich Vereshchagin for the particular case of robotic arms, and later generalized to all mechanical systems by Firdaus E. Udwadia and Robert E. Kalaba in 1992. The approach is based on Gauss's principle of least constraint. The Udwadia–Kalaba method applies to both holonomic constraints and nonholonomic constraints, as long as they are linear with respect to the accelerations. The method generalizes to constraint forces that do not obey D'Alembert's principle.

In continuum mechanics, a compatible deformation tensor field in a body is that unique tensor field that is obtained when the body is subjected to a continuous, single-valued, displacement field. Compatibility is the study of the conditions under which such a displacement field can be guaranteed. Compatibility conditions are particular cases of integrability conditions and were first derived for linear elasticity by Barré de Saint-Venant in 1864 and proved rigorously by Beltrami in 1886.

Orbit modeling is the process of creating mathematical models to simulate motion of a massive body as it moves in orbit around another massive body due to gravity. Other forces such as gravitational attraction from tertiary bodies, air resistance, solar pressure, or thrust from a propulsion system are typically modeled as secondary effects. Directly modeling an orbit can push the limits of machine precision due to the need to model small perturbations to very large orbits. Because of this, perturbation methods are often used to model the orbit in order to achieve better accuracy.

In theoretical physics, relativistic Lagrangian mechanics is Lagrangian mechanics applied in the context of special relativity and general relativity.