William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard was an American military officer known as being the Confederate General who started the American Civil War at the battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Today, he is commonly referred to as P. G. T. Beauregard, but he rarely used his first name as an adult. He signed correspondence as G. T. Beauregard.

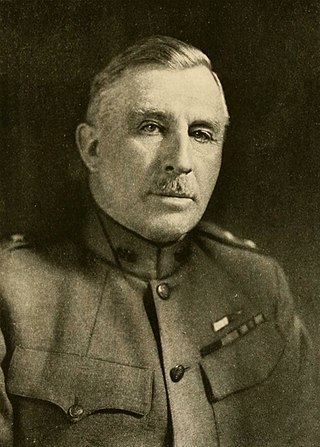

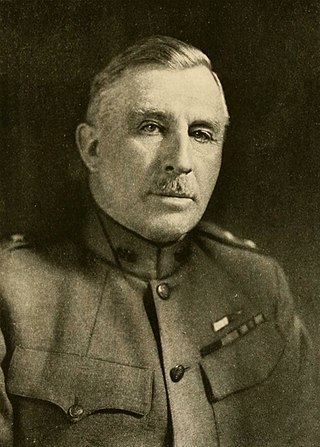

Leonard Wood was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Military Governor of Cuba, and Governor-General of the Philippines. He began his military career as an army doctor on the frontier, where he received the Medal of Honor. During the Spanish–American War, he commanded the Rough Riders, with Theodore Roosevelt as his second-in-command. Wood was bypassed for a major command in World War I, but then became a prominent Republican Party leader and a leading candidate for the 1920 presidential nomination.

Asa Philip Randolph was an American labor unionist and civil rights activist. In 1925, he organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first successful African-American-led labor union. In the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement, Randolph was a prominent voice. His continuous agitation with the support of fellow labor rights activists against racist labor practices helped lead President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941, banning discrimination in the defense industries during World War II. The group then successfully maintained pressure, so that President Harry S. Truman proposed a new Civil Rights Act and issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 in 1948, promoting fair employment and anti-discrimination policies in federal government hiring, and ending racial segregation in the armed services.

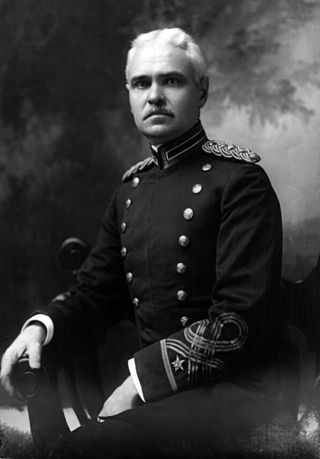

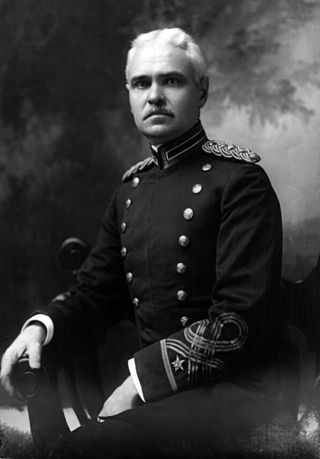

George Washington Goethals was a United States Army general and civil engineer, best known for his administration and supervision of the construction and the opening of the Panama Canal. He was the State Engineer of New Jersey and the Acting Quartermaster General of the United States Army.

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front during World War I, comprised mostly of units from the U.S. Army. The AEF was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of then-Major General John J. Pershing. It fought alongside French Army, British Army, Canadian Army, British Indian Army, New Zealand Army and Australian Army units against the Imperial German Army. A small number of AEF troops also fought alongside Italian Army units in 1918 against the Austro-Hungarian Army. The AEF helped the French Army on the Western Front during the Aisne Offensive in the summer of 1918, and fought its major actions in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the latter part of 1918.

Audie Leon Murphy was an American soldier, actor, and songwriter. He was widely celebrated as the most decorated American combat soldier of World War II, and has been described as the most highly decorated soldier in U.S. history. He received every military combat award for valor available from the United States Army, as well as French and Belgian awards for heroism. Murphy received the Medal of Honor for valor that he demonstrated at the age of 19 for single-handedly holding off a company of German soldiers for an hour at the Colmar Pocket in France in January 1945, before leading a successful counterattack while wounded and out of ammunition.

Sherman's March to the Sea was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, major general of the Union Army. The campaign began on November 15 with Sherman's troops leaving Atlanta, recently taken by Union forces, and ended with the capture of the port of Savannah on December 21. His forces followed a "scorched earth" policy, destroying military targets as well as industry, infrastructure, and civilian property, disrupting the Confederacy's economy and transportation networks. The operation debilitated the Confederacy and helped lead to its eventual surrender. Sherman's decision to operate deep within enemy territory without supply lines was unusual for its time, and the campaign is regarded by some historians as an early example of modern warfare or total war.

Robert Gould Shaw was an American officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Born into a Boston upper class abolitionist family, he accepted command of the first all-black regiment in the Northeast. Supporting the promised equal treatment for his troops, he encouraged the men to refuse their pay until it was equal to that of white troops' wage.

The 369th Infantry Regiment, originally formed as the 15th New York National Guard Regiment before it was re-organized as the 369th upon its federalization and commonly referred to as the Harlem Hellfighters, was an infantry regiment of the New York Army National Guard during World War I and World War II. The regiment mainly consisted of African Americans, but it also included men from Puerto Rico, Cuba, Guyana, Liberia, Portugal, Canada, the West Indies, as well as white American officers. With the 370th Infantry Regiment, it was known for being one of the first African-American regiments to serve with the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I.

Benjamin Oliver Davis Sr. was a career officer in the United States Army. One of the few black officers in an era when American society was largely segregated, in 1940 he was promoted to brigadier general, the army's first African American general officer.

Noble Lee Sissle was an American jazz composer, lyricist, bandleader, singer, and playwright, best known for the Broadway musical Shuffle Along (1921), and its hit song "I'm Just Wild About Harry".

The 93rd Infantry Division was a "colored" segregated unit of the United States Army in World War I and World War II. However, in World War I only its four infantry regiments, two brigade headquarters, and a provisional division headquarters were organized, and the divisional and brigade headquarters were demobilized in May 1918. Its regiments fought primarily under French command in that war and saw action during the Second Battle of the Marne. They acquired the nickname Blue Helmets from the French, as these units were issued horizon blue French Adrian helmets. Consequently, its shoulder patch became a blue French helmet, to commemorate its service with the French Army during the German spring offensive.

The 366th Infantry Regiment was an all African American (segregated) unit of the United States Army that served in both World War I and World War II. In the latter war, the unit was exceptional for having all black officers as well as troops. The U.S. military did not desegregate until after World War II. During the war, for most of the segregated units, all field grade and most of the company grade officers were white.

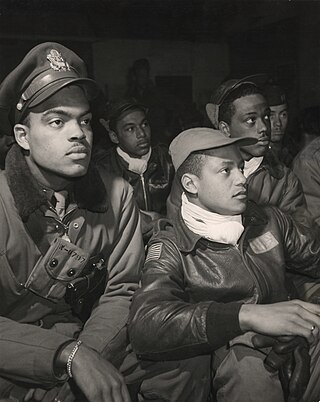

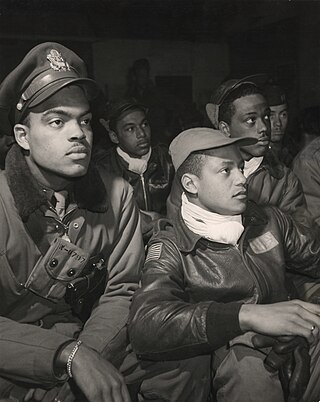

The military history of African Americans spans from the arrival of the first enslaved Africans during the colonial history of the United States to the present day. African Americans have participated in every war fought by or within the United States, including the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the Civil War, the Spanish–American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War.

African Americans, including former slaves, served in the American Civil War. The 186,097 black men who joined the Union Army included 7,122 officers and 178,975 enlisted soldiers. Approximately 20,000 black sailors served in the Union Navy and formed a large percentage of many ships' crews. Later in the war, many regiments were recruited and organized as the United States Colored Troops, which reinforced the Northern forces substantially during the conflict's last two years. Both Northern Free Negro and Southern runaway slaves joined the fight. Throughout the course of the war, black soldiers served in forty major battles and hundreds of more minor skirmishes; sixteen African Americans received the Medal of Honor.

Walter Edward Williams was an American economist, commentator, and academic. Williams was the John M. Olin Distinguished Professor of Economics at George Mason University, as well as a syndicated columnist and author. Known for his classical liberal and libertarian views, Williams's writings frequently appeared in Townhall, WND, and Jewish World Review. Williams was also a popular guest host of the Rush Limbaugh radio show when Limbaugh was unavailable.

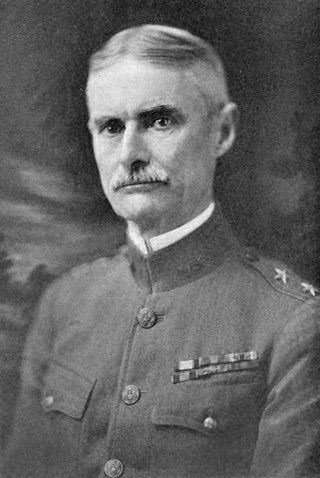

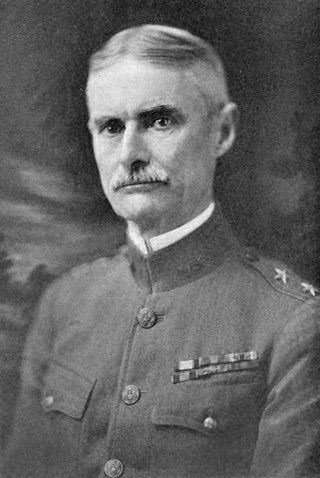

William Henry Hay was a United States Army officer who attained the rank of major general as the commander of the 28th Division in the final days of World War I.

Henry Demas was an enslaved African American who became a constable, state legislator, civil rights activist, and organizer of Southern University in Louisiana during the Reconstruction era.

After young African-American men volunteered to fight against the Central Powers, during World War I, many of them returned home but instead of being rewarded for their military service, they were subjected to discrimination, racism and lynchings by the citizens and the government. Labor shortages in essential industries caused a massive migration of southern African-Americans to northern cities leading to a wide-spread emergency of segregation in the north and the regeneration of the Ku Klux Klan. For many African-American veterans, as well as the majority of the African-Americans in the United States, the times which followed the war were fraught with challenges similar to those they faced overseas. Discrimination and segregation were at the forefront of everyday life, but most prevalent in schools, public revenues, and housing. Although members of different races who had fought in World War I believed that military service was a price which was worth paying in exchange for equal citizenship, this was not the case for African-Americans. The decades which followed World War I included blatant acts of racism and nationally recognized events which conveyed American society's portrayal of African-Americans as 2nd class citizens. Although the United States had just won The Great War in 1918, the national fight for equal rights was just beginning.