Dom Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu, better known as Prince Henry the Navigator, was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15th-century European maritime discoveries and maritime expansion. Through his administrative direction, he is regarded as the main initiator of what would be known as the Age of Discovery. Henry was the fourth child of King John I of Portugal, who founded the House of Aviz.

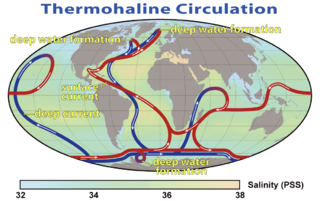

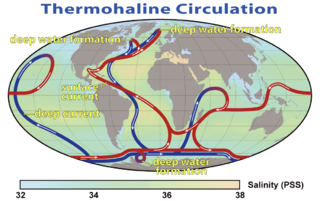

Oceanography, also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynamics; plate tectonics and seabed geology; and fluxes of various chemical substances and physical properties within the ocean and across its boundaries. These diverse topics reflect multiple disciplines that oceanographers utilize to glean further knowledge of the world ocean, including astronomy, biology, chemistry, geography, geology, hydrology, meteorology and physics. Paleoceanography studies the history of the oceans in the geologic past. An oceanographer is a person who studies many matters concerned with oceans, including marine geology, physics, chemistry, and biology.

Sir Thomas Cavendish was an English explorer and a privateer known as "The Navigator" because he was the first who deliberately tried to emulate Sir Francis Drake and raid the Spanish towns and ships in the Pacific and return by circumnavigating the globe. Magellan's, Loaisa's, Drake's, and Loyola's expeditions had preceded Cavendish in circumnavigating the globe. His first trip and successful circumnavigation made him rich from captured Spanish gold, silk and treasure from the Pacific and the Philippines. His richest prize was the captured 600-ton sailing ship the Manila Galleon Santa Ana. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I of England after his return. He later set out for a second raiding and circumnavigation trip but was not as fortunate and died at sea at the age of 31.

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships developed in Spain and first used as armed cargo carriers by Europeans from the 16th to 18th centuries during the Age of Sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the mid-1600s. Galleons generally carried three or more masts with a lateen fore-and-aft rig on the rear masts, were carvel built with a prominent squared off raised stern, and used square-rigged sail plans on their fore-mast and main-masts.

The Manila galleon, originally known as La Nao de China, and Galeón de Acapulco, refers to the Spanish trading ships that linked the Spanish Crown's Viceroyalty of New Spain, based in Mexico City, with its Asian territories, collectively known as the Spanish East Indies, across the Pacific Ocean. The ships made one or two round-trip voyages per year between the ports of Acapulco and Manila from the late 16th to early 19th century. The name of the galleon changed to reflect from which city the ship sailed, setting sail from Cavite, in Manila Bay, at the end of June or first week of July, starting the return journey (tornaviaje) from Acapulco in March–April of the next calendar year, and returning to Manila in June–July.

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, strengthening during the winter and when the Arctic oscillation is in its warm phase. Trade winds have been used by captains of sailing ships to cross the world's oceans for centuries. They enabled European colonization of the Americas, and trade routes to become established across the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.

The Age of Discovery, also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and largely overlapping with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the late 15th century to the 17th century, during which seafarers from a number of European countries explored, colonized, and conquered regions across the globe. The Age of Discovery was a transformative period in world history when previously isolated parts of the world became connected to form the world system and laid the groundwork for globalization. The extensive overseas exploration, particularly the European colonization of the Americas, with the Spanish, Portuguese, and later the English, spurred in the International global trade. The interconnected global economy of the 21st century has its roots in the expansion of trade networks during this era.

Andrés de Urdaneta was a maritime explorer for the Spanish Empire of Basque heritage, who became an Augustinian friar. At the age of seventeen, he formed part of the Loaísa expedition to the Spice Islands where he spent more than eight years. Around 1540 he settled in New Spain and became an Augustinian friar in 1552. At the request of Philip II he joined the Legazpi expedition for a return to the Philippines. In 1565, Urdaneta discovered and plotted an easterly route across the Pacific Ocean, from the Philippines to Acapulco in the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The route made it practical for Spain to colonize the Philippines and was used as the Manila galleon trade route for more than two hundred years.

Diogo de Silves is the presumed name of an obscure Portuguese explorer of the Atlantic who allegedly discovered the Azores islands in 1427.

Gaspar de Lemos was a Portuguese explorer and captain of the supply ship of Pedro Álvares Cabral's fleet that arrived to Brazil. Gaspar de Lemos was sent back to Portugal with news of their discovery and was credited by the Viscount of Santarém as having discovered the Fernando de Noronha archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean.

The Loaísa expedition was an early 16th-century Spanish voyage of discovery to the Pacific Ocean, commanded by García Jofre de Loaísa and ordered by King Charles I of Spain to colonize the Spice Islands in the East Indies. The seven-ship fleet sailed from La Coruña, Spain in July 1525 and became the second naval expedition in history to cross the Pacific Ocean, after the Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation. The expedition resulted in the discovery of the Sea of Hoces south of Cape Horn, and the Marshall Islands in the Pacific. One ship ultimately arrived in the Spice Islands in September 1526.

The history of navigation, or the history of seafaring, is the art of directing vessels upon the open sea through the establishment of its position and course by means of traditional practice, geometry, astronomy, or special instruments. Many peoples have excelled as seafarers, prominent among them the Austronesians, the Harappans, the Phoenicians, the Iranians, the ancient Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the ancient Indians, the Norse, the Chinese, the Venetians, the Genoese, the Hanseatic Germans, the Portuguese, the Spanish, the English, the French, the Dutch, and the Danes.

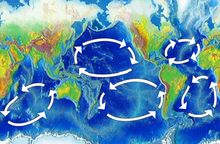

The captain of a steam ship naturally chooses the shortest route to nearby destinations. Since a sailing ship is usually pushed by winds and currents, its captain must find a route where the wind will probably blow in the right direction. Tacking, i.e. using contrary wind to pull (sic) the sails, was always possible but wasted time because of the zigzagging required, and this would significantly delay long voyages. The early European explorers were not only looking for new lands. They also had to discover the pattern of winds and currents that would carry them where they wanted to go. During the Age of Sail winds and currents determined trade routes and therefore influenced European imperialism and modern political geography. For an outline to the main wind systems see Global wind patterns.

The Portuguese Indian Armadas were the fleets of ships funded by the Crown of Portugal, and dispatched on an annual basis from Portugal to India. The principal destination was Goa, and previously Cochin. These armadas undertook the Carreira da Índia from Portugal, following the maritime discovery of the Cape route, to the Indian subcontinent by Vasco da Gama in 1497–99.

Due to centuries of constant conflict, warfare and daily life in the Iberian Peninsula were interlinked. Small, lightly equipped armies were maintained at all times. The near-constant state of war resulted in a need for maritime experience, ship technology, power, and organization. This led the Crowns of Aragon, Portugal, and later Castile, to put their efforts into the sea.

The Pacific Coast of Mexico or West Coast of Mexico stretches along the coasts of western Mexico at the Pacific Ocean and its Gulf of California.

Early Polynesian explorers reached nearly all Pacific islands by 1200 CE, followed by Asian navigation in Southeast Asia and the West Pacific. During the Middle Ages, Muslim traders linked the Middle East and East Africa to the Asian Pacific coasts, reaching southern China and much of the Malay Archipelago. Direct European contact with the Pacific began in 1512, with the Portuguese encountering its western edges, soon followed by the Spanish arriving from the American coast.

The School of Sagres, also called Court of Sagres is supposed to have been a group of figures associated with fifteenth century Portuguese navigation, gathered by prince Henry of Portugal in Sagres near Cape St. Vincent, the southwestern end of the Iberian Peninsula, in the Algarve.

Thomas Cavendish's circumnavigation was a voyage of raid and exploration by English navigator and sailor Thomas Cavendish which took place during the Anglo–Spanish War between 21 July 1586 and 9 September 1588. Following in the footsteps of Francis Drake who circumnavigated the globe, Thomas Cavendish was influenced in an attempt to repeat the feat. As such it was the first deliberately planned voyage of the globe.

Portuguese nautical science evolved from the successive expeditions and experience of the Portuguese pilots. It led to a fairly rapid evolution, creating an elite of astronomers, navigators, mathematicians and cartographers. Among them stood Pedro Nunes with studies on how to determine latitude by the stars, and João de Castro, who made important observations of magnetic declination over the entire route around Africa.