Çatalhöyük was a very large Neolithic and Chalcolithic proto-city settlement in southern Anatolia, which existed from approximately 7100 BC to 5700 BC, and flourished around 7000 BC. In July 2012, it was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Midas is the name of one of at least three members of the royal house of Phrygia.

Neolithic architecture refers to structures encompassing housing and shelter from approximately 10,000 to 2,000 BC, the Neolithic period. In southwest Asia, Neolithic cultures appear soon after 10,000 BC, initially in the Levant and from there into the east and west. Early Neolithic structures and buildings can be found in southeast Anatolia, Syria, and Iraq by 8,000 BC with agriculture societies first appearing in southeast Europe by 6,500 BC, and central Europe by ca. 5,500 BC (of which the earliest cultural complexes include the Starčevo-Koros, Linearbandkeramic, and Vinča.

A tumulus is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or kurgans, and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones built for various purposes, may also originally have been a tumulus.

A gallery grave is a form of megalithic tomb built primarily during the Neolithic Age in Europe in which the main gallery of the tomb is entered without first passing through an antechamber or hallway. There are at least four major types of gallery grave, and they may be covered with an earthen mound or rock mound.

Bucranium was a form of carved decoration commonly used in Classical architecture. The name is generally considered to originate with the practice of displaying garlanded, sacrificial oxen, whose heads were displayed on the walls of temples, a practice dating back to the sophisticated Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in eastern Anatolia, where cattle skulls were overlaid with white plaster.

The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations is located on the south side of Ankara Castle in the Atpazarı area in Ankara, Turkey. It consists of the old Ottoman Mahmut Paşa bazaar storage building, and the Kurşunlu Han. Because of Atatürk's desire to establish a Hittite museum, the buildings were bought upon the suggestion of Hamit Zübeyir Koşay, who was then Culture Minister, to the National Education Minister, Saffet Arıkan. After the remodelling and repairs were completed (1938–1968), the building was opened to the public as the Ankara Archaeological Museum.

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions is an archaeological site at the ancient city of Veii, Italy. It is best known for its well-preserved fresco paintings of four feline-like creatures, believed by archaeologists to depict lions. The tomb is believed to be one of the oldest painted tombs in the western Mediterranean, dating back to 690 BCE. The discovery of the Tomb allowed archaeologists a greater insight into funerary practices amongst the Etruscan people, while providing insight into art movements around this period of time. The fresco paintings on the wall of the tomb are a product of advances in trade that allowed artists in Veii to be exposed to art making practices and styles of drawing originating from different cultures, in particular geometric art movements in Greece. The lions were originally assumed to be caricatures of lions – created by artists who had most likely never seen the real animal in flesh before.

Alacahöyük or Alaca Höyük is the site of a Neolithic and Hittite settlement and is an important archaeological site. It is situated in Alaca, Çorum Province, Turkey, northeast of Boğazkale, where the ancient capital city Hattusa of the Hittite Empire was situated. Its Hittite name is unknown: connections with Arinna, Tawiniya, and Zippalanda have all been suggested.

Aşıklı Höyük is a settlement mound located nearly 1 km south of Kızılkaya village on the bank of the Melendiz brook, and 25 kilometers southeast of Aksaray, Turkey. Aşıklı Höyük is located in an area covered by the volcanic tuff of central Cappadocia, in Aksaray Province. The archaeological site of Aşıklı Höyük was first settled in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, around 8,200 BC.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

The Tumulus of Bougon or Necropolis of Bougon is a group of five Neolithic barrows located in Bougon near La-Mothe-Saint-Héray, between Exoudon and Pamproux in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France. Their discovery in 1840 raised great scientific interest. To protect the monuments, the site was acquired by the department of Deux-Sèvres in 1873. Excavations resumed in the late 1960s. The oldest structures of this prehistoric monument date to 4800 BC.

Gordion was the capital city of ancient Phrygia. It was located at the site of modern Yassıhüyük, about 70–80 km (43–50 mi) southwest of Ankara, in the immediate vicinity of Polatlı district. Gordion's location at the confluence of the Sakarya and Porsuk rivers gave it a strategic location with control over fertile land. Gordion lies where the ancient road between Lydia and Assyria/Babylonia crossed the Sangarius river. Occupation at the site is attested from the Early Bronze Age continuously until the 4th century CE and again in the 13th and 14th centuries CE. The Citadel Mound at Gordion is approximately 13.5 hectares in size, and at its height habitation extended beyond this in an area approximately 100 hectares in size. Gordion is the type site of Phrygian civilization, and its well-preserved destruction level of c. 800 BCE is a chronological linchpin in the region. The long tradition of tumuli at the site is an important record of elite monumentality and burial practice during the Iron Age.

Gözlükule is a tumulus within the borders of Tarsus city, Mersin Province, Turkey. It is now a park with an altitude of 22 metres (72 ft) with respect to surrounding area.

A spectacular collection of furniture and wooden artifacts was excavated by the University of Pennsylvania at the site of Gordion, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Phrygia in the early first millennium BC. The best preserved of these works came from three royal burials, surviving nearly intact due to the relatively stable conditions that had prevailed inside the tomb chambers. The Gordion wooden objects are now recognized as the most important collection of wooden finds recovered from the ancient Near East.

The prehistory of Anatolia stretches from the Paleolithic era through to the appearance of classical civilisation in the middle of the 1st millennium BC. It is generally regarded as being divided into three ages reflecting the dominant materials used for the making of domestic implements and weapons: Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. The term Copper Age (Chalcolithic) is used to denote the period straddling the stone and Bronze Ages.

Part of series of articles upon Archaeology of Kosovo

Elizabeth Simpson is an archaeologist, art historian, illustrator, and professor emerita at the Bard Graduate Center, New York, NY, where she taught for 25 years. She is director of the project to study, conserve, and publish the large collection of rare wooden artifacts from Gordion, Turkey, which date to the eighth century BC. In this capacity, she is a consulting scholar in the Mediterranean Section, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. She received her PhD in classical archaeology from the University of Pennsylvania in 1985.

The Tomb of Macridy Bey (Greek: Τάφος Μακρίδη Μπέη, romanized: tafos makridi bei, also known as the Tomb of Langadas, is an ancient Macedonian tomb of the Classical or early Hellenistic period, on the site of ancient Lete, modern Derveni between Thessaloniki and Langadas, in Central Macedonia, Greece. A number of cist graves and a single chamber tomb are located in the vicinity. The structure seems to date to the late fourth or early third century BCE.

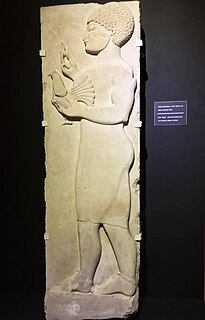

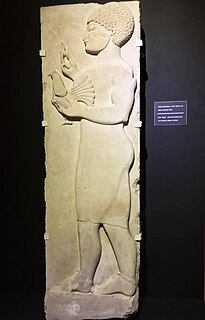

The Gökçeler relief is an Achaemenid-era tomb relief made in the Anatolian-Persian style. It was found in 2004 in the village of Gökçeler in Manisa Province of present-day Turkey. The area of discovery corresponds to the northern part of the historic region of Lydia, at a time when it was a satrapy (province) of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The relief is made out of limestone and measures 1.79m × 0.55m × 0.25m. The relief is a "distinctive product of the artistic synthesis classified as Graeco-Persian or Anatolian-Persian". It was created between the late 6th century and early 5th century BC. It may be used as "yet further evidence for the presence of Persians in the region".