Historical group

The term "war hawk" was coined in 1792 and was often used to ridicule politicians who favored a pro-war policy in peacetime. Historian Donald R. Hickey found 129 uses of the term in American newspapers before late 1811, mostly from Federalists warning against Democratic-Republican foreign policy. Some antiwar Democratic-Republicans used it, such as Virginia Congressman John Randolph of Roanoke. [2] There was never any "official" roster of War Hawks; as Hickey notes, "Scholars differ over who (if anyone) ought to be classified as a War Hawk." [3] However, most historians use the term to describe about one or two dozen members of the Twelfth Congress. The leader of this faction was Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina was another notable War Hawk. Both of these men became major players in American politics for decades, despite failing to win the presidency themselves. Other men traditionally identified as War Hawks include Richard Mentor Johnson of Kentucky, William Lowndes of South Carolina, Langdon Cheves of South Carolina, Felix Grundy of Tennessee, and William W. Bibb of Georgia. [1]

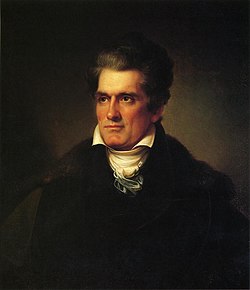

President James Madison set the legislative agenda for Congress, providing committees in the House of Representatives with policy recommendations to be introduced as bills on the House floor. [4] Nevertheless, he was regarded as a "timid soul" and tried to restrain the martial zeal of the War Hawks. [1]