History

In August 1914, after discovering that Germany had a Propaganda Agency, David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was given the task of setting up a British War Propaganda Bureau. Lloyd George appointed the writer and fellow Liberal MP, Charles Masterman to head the organization, whose headquarters were set up at Wellington House, the London headquarters of the National Insurance Commission, of which Masterman was the chairman.

The Bureau began its propaganda campaign on 2 September 1914 when Masterman invited 25 leading British authors to Wellington House to discuss ways of best promoting Britain's interests during the war. Those who attended included William Archer, Hall Caine, Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, G. K. Chesterton, Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Gilbert Parker, G. M. Trevelyan and H. G. Wells. [2] Rudyard Kipling had been invited to the meeting but was unable to attend.

All the writers who attended agreed to maintain the utmost secrecy, and it was not until 1935 that the activities of the War Propaganda Bureau became public knowledge. Several of the writers agreed to write pamphlets and books that would promote the government's point of view; these were printed and published by such well-known publishers as Hodder & Stoughton, Methuen, Oxford University Press, John Murray, Macmillan and Thomas Nelson. The War Propaganda Bureau went on to publish over 1,160 pamphlets during the war.

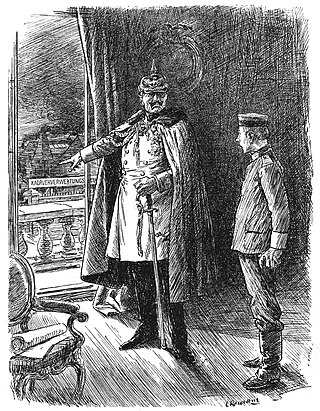

One of the first significant publications to be produced by the Bureau was the Report on Alleged German Outrages , in early 1915. This pamphlet documented atrocities both actual and alleged committed by the German army against Belgian civilians. A Dutch illustrator, Louis Raemaekers, provided highly emotional drawings which appeared in the pamphlet.

One of Masterman's early projects was a history of the war to be published as a monthly magazine, for which he recruited John Buchan to head its production. Published by Buchan's own publishers, Thomas Nelson, the first installment of the Nelson's History of the War appeared in February 1915. A further 23 editions appeared regularly during the war. Buchan was given the rank of Second Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps and provided with the necessary documents to write the work. General Headquarters Staff saw this as very good for propaganda as Buchan's close relationship with Britain's military leaders made it very difficult for him to include any criticism about the way the war was being conducted.

After January 1916 the Bureau's activities were subsumed under the office of the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. In May 1916 Masterman recruited artist Muirhead Bone. He was sent to France and by October had produced 150 drawings. After Bone returned to England he was replaced by his brother-in-law, Francis Dodd, who had been working for the Manchester Guardian . In 1917 arrangements were made to send other artists to France including Eric Kennington, William Orpen, Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson and William Rothenstein. John Lavery was recruited to paint pictures of the home front. Nash later complained about the strict control maintained by the Bureau over the official subject matter, saying "I am no longer an artist. I am an artist who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on forever. Feeble, inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth and may it burn their lousy souls."

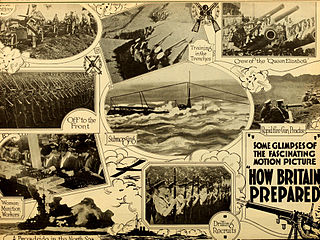

In February 1917 the government established a Department of Information. John Buchan was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and put in charge of it at an annual salary of £1,000. Masterman retained responsibility for books, pamphlets, photographs and war art, while T. L. Gilmour was responsible for telegraph communications, radio, newspapers, magazines and the cinema.

In early 1918 it was decided that a senior government figure should take over responsibility for propaganda and on 4 March Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express newspaper, was made Minister of Information. Masterman was placed beneath him as Director of Publications, and John Buchan as Director of Intelligence. Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Times and the Daily Mail , was put in charge of propaganda aimed at enemy nations, while Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle , was made director of propaganda aimed at neutral nations. Following the announcement, in February 1918, Lloyd George was accused of creating this new system to gain control over Fleet Street's leading figures.