Related Research Articles

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilisation in which it appears. In Western culture, depending on the particular nation, conservatives seek to promote and preserve a range of institutions, such as the nuclear family, organised religion, the military, the nation-state, property rights, rule of law, aristocracy, and monarchy. Conservatives tend to favour institutions and practices that enhance social order and historical continuity.

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

The Bloomsbury Group was a group of associated British writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century. Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, and Lytton Strachey. Their works and outlook deeply influenced literature, aesthetics, criticism, and economics, as well as modern attitudes towards feminism, pacifism, and sexuality.

Totalitarian democracy is a dictatorship based on the mass enthusiasm generated by a perfectionist ideology. The conflict between the state and the individual should not exist in a totalitarian democracy, and in the event of such a conflict, the state has the moral duty to coerce the individual to obey. This idea that there is one true way for a society to be organized and a government should get there at all costs stands in contrast to liberal democracy which trusts the process of democracy to, through trial and error, help a society improve without there being only one correct way to self-govern.

Satyāgraha, or "holding firmly to truth", or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone who practises satyagraha is a satyagrahi.

Jeane Duane Kirkpatrick was an American diplomat and political scientist who played a major role in the foreign policy of the Ronald Reagan administration. An ardent anticommunist, she was a longtime Democrat who became a neoconservative and switched to the Republican Party in 1985. After serving as Ronald Reagan's foreign policy adviser in his 1980 presidential campaign, she became the first woman to serve as United States Ambassador to the United Nations.

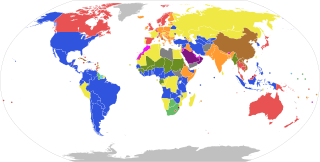

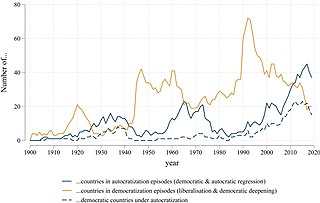

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

Reza Pahlavi is the eldest son of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, and his wife Farah Diba. Before the Islamic Revolution in 1979, he was the crown prince and the last heir apparent to the throne of the Imperial State of Iran. Pahlavi resides in Great Falls, Virginia.

Power: A New Social Analysis by Bertrand Russell is a work in social philosophy written by Bertrand Russell. Power, for Russell, is one's ability to achieve goals. In particular, Russell has in mind social power, that is, power over people.

What constitutes a definition of fascism and fascist governments has been a complicated and highly disputed subject concerning the exact nature of fascism and its core tenets debated amongst historians, political scientists, and other scholars ever since Benito Mussolini first used the term in 1915. Historian Ian Kershaw once wrote that "trying to define 'fascism' is like trying to nail jelly to the wall".

Past and Present is a book by the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle. It was published in April 1843 in England and the following month in the United States. It combines medieval history with criticism of 19th-century British society. Carlyle wrote it in seven weeks as a respite from the harassing labor of writing Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches. He was inspired by the recently published Chronicles of the Abbey of Saint Edmund's Bury, which had been written by Jocelin of Brakelond at the close of the 12th century. This account of a medieval monastery had taken Carlyle's fancy, and he drew upon it in order to contrast the monks' reverence for work and heroism with the sham leadership of his own day.

The Beijing Consensus or China Model, also known as the Chinese Economic Model, is the political and economic policies of the People's Republic of China (PRC) that began to be instituted by Hua Guofeng and Deng Xiaoping after Mao Zedong's death in 1976. The policies are thought to have contributed to China's "economic miracle" and eightfold growth in gross national product over two decades. In 2004, the phrase "Beijing Consensus" was coined by Joshua Cooper Ramo to frame China's economic development model as an alternative—especially for developing countries—to the Washington Consensus of market-friendly policies promoted by the IMF, World Bank, and U.S. Treasury. In 2016, Ramo explained that the Beijing Consensus shows not that "every nation will follow China's development model, but that it legitimizes the notion of particularity as opposed to the universality of a Washington model".

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political status quo, and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and the rule of law. Political scientists have created many typologies describing variations of authoritarian forms of government. Authoritarian regimes may be either autocratic or oligarchic and may be based upon the rule of a party or the military. States that have a blurred boundary between democracy and authoritarianism have some times been characterized as "hybrid democracies", "hybrid regimes" or "competitive authoritarian" states.

Criticism of democracy, or debate on democracy and the different aspects of how to implement democracy best have been widely discussed. There are both internal critics and external ones who reject the values promoted by constitutional democracy.

Anarchy is a form of society without rulers. As a type of stateless society, it is commonly contrasted with states, which are centralised polities that claim a monopoly on violence over a permanent territory. Beyond a lack of government, it can more precisely refer to societies that lack any form of authority or hierarchy. While viewed positively by anarchists, the primary advocates of anarchy, it is viewed negatively by advocates of statism, who see it in terms of social disorder.

Authoritarian socialism, or socialism from above, is an economic and political system supporting some form of socialist economics while rejecting political pluralism. As a term, it represents a set of economic-political systems describing themselves as "socialist" and rejecting the liberal-democratic concepts of multi-party politics, freedom of assembly, habeas corpus, and freedom of expression, either due to fear of counter-revolution or as a means to socialist ends. Journalists and scholars have characterised several countries, most notably the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, and their allies, as authoritarian socialist states.

A hybrid regime is a type of political system often created as a result of an incomplete democratic transition from an authoritarian regime to a democratic one. Hybrid regimes are categorized as having a combination of autocratic features with democratic ones and can simultaneously hold political repressions and regular elections. Hybrid regimes are commonly found in developing countries with abundant natural resources such as petro-states. Although these regimes experience civil unrest, they may be relatively stable and tenacious for decades at a time. There has been a rise in hybrid regimes since the end of the Cold War.

The Power of the Powerless is an expansive political essay written in October 1978 by the Czech dramatist, political dissident, and later statesman, Václav Havel.

The Dark Enlightenment, also called the neo-reactionary movement, is an anti-democratic, anti-egalitarian, reactionary philosophical and political movement. The term "Dark Enlightenment" is a reaction to the Age of Enlightenment and apologia for the public view of the "Dark Ages".

Two Cheers for Democracy is the second collection of essays by E. M. Forster, published in 1951, and incorporating material from 1936 onwards.

References

- ↑ Spender, Stephen (1998). E.M. Forster : critical assessments. Stape, J. H. (John Henry). Mountfield near Robertsbridge, East Sussex: Helm Information. pp. 245–256. ISBN 1873403372. OCLC 39775471.