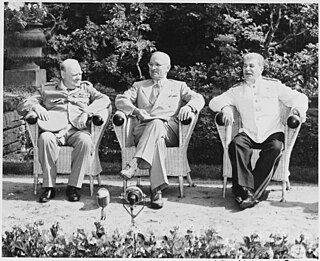

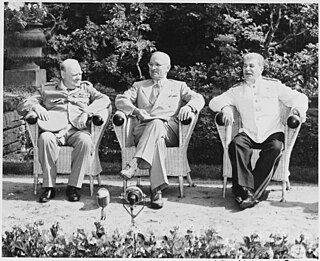

The Potsdam Conference was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They were represented respectively by General Secretary Joseph Stalin, Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee, and President Harry S. Truman. They gathered to decide how to administer Germany, which had agreed to an unconditional surrender nine weeks earlier. The goals of the conference also included establishing the postwar order, solving issues on the peace treaty, and countering the effects of the war.

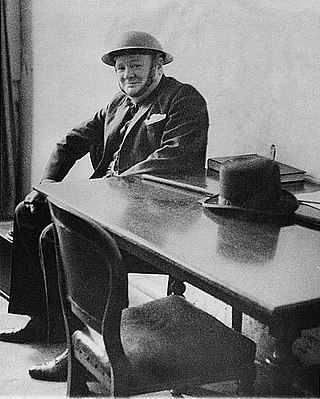

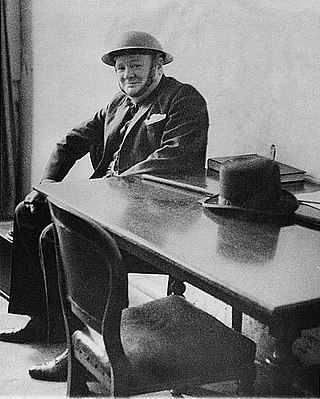

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 and again from 1951 to 1955. Apart from 1922 to 1924, he was a member of Parliament (MP) from 1900 to 1964 and represented a total of five constituencies. Ideologically an adherent to economic liberalism and imperialism, he was for most of his career a member of the Conservative Party, which he led from 1940 to 1955. He was a member of the Liberal Party from 1904 to 1924.

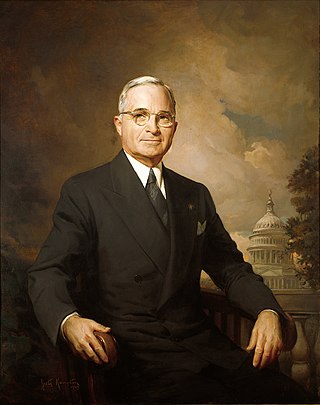

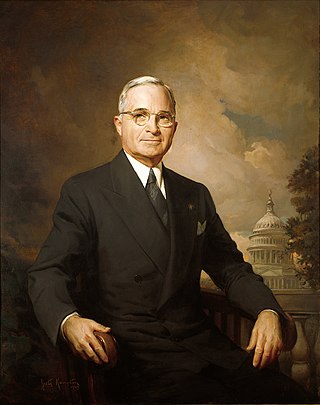

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledges American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of countering the growth of the Soviet bloc during the Cold War. It was announced to Congress by President Harry S. Truman on March 12, 1947, and further developed on July 4, 1948, when he pledged to oppose the communist rebellions in Greece and Soviet demands from Turkey. More generally, the Truman Doctrine implied American support for other nations threatened by Moscow. It led to the formation of NATO in 1949. Historians often use Truman's speech to Congress on March 12, 1947, to date the start of the Cold War.

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II, months before the US officially entered the war. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and the United Kingdom for the postwar world as follows: no territorial aggrandizement, no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people (self-determination), restoration of self-government to those deprived of it, reduction of trade restrictions, global co-operation to secure better economic and social conditions for all, freedom from fear and want, freedom of the seas, abandonment of the use of force, and disarmament of aggressor nations. The charter's adherents signed the Declaration by United Nations on 1 January 1942, which was the basis for the modern United Nations.

Ernest Bevin was a British statesman, trade union leader and Labour Party politician. He cofounded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union from 1922 to 1940 and served as Minister of Labour and National Service in the wartime coalition government. He succeeded in maximising the British labour supply for both the armed services and domestic industrial production with a minimum of strikes and disruption.

The Special Relationship is a term that is often used to describe the political, social, diplomatic, cultural, economic, legal, environmental, religious, military and historic relations between the United Kingdom and the United States or its political leaders. The term first came into popular usage after it was used in a 1946 speech by former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Both nations have been close allies during many conflicts in the 20th and the 21st centuries, including World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Cold War, the Gulf War and the war on terror.

The phrase "blood, toil, tears and sweat" became famous in a speech given by Winston Churchill to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom on 13 May 1940. The speech is sometimes known by that name.

Relations between the United Kingdom and the United States have ranged from military opposition to close allyship since 1776. The Thirteen Colonies seceded from the Kingdom of Great Britain and declared independence in 1776, fighting a successful revolutionary war. While Britain was fighting Napoleon, the two nations fought the stalemated War of 1812. Relations were generally positive thereafter, save for a short crisis in 1861 during the American Civil War. By the 1880s, the US economy had surpassed Britain's; in the 1920s, New York City surpassed London as the world's leading financial center. The two nations fought Germany together during the two World Wars; since 1940, the two countries have been close military allies, enjoying the Special Relationship built as wartime allies and NATO and G7 partners.

The Second Cairo Conference of December 4–6, 1943, held in Cairo, Egypt, addressed Turkey's possible contribution to the Allies in World War II. The meeting was attended by President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the United States, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, and President İsmet İnönü of the Republic of Turkey.

The Churchill caretaker ministry was a short-term British government in the latter stages of the Second World War, from 23 May to 26 July 1945. The prime minister was Winston Churchill, leader of the Conservative Party. This government succeeded the national coalition which he had formed after he was first appointed prime minister on 10 May 1940. The coalition had comprised leading members of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal parties and it was terminated soon after the defeat of Nazi Germany because the parties could not agree on whether it should continue until after the defeat of Japan.

Winston Churchill's Conservative Party lost the July 1945 general election, forcing him to step down as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. For six years he served as the Leader of the Opposition. During these years he continued to influence world affairs. In 1946 he gave his "Iron Curtain" speech which spoke of the expansionist policies of the Soviet Union and the creation of the Eastern Bloc; Churchill also argued strongly for British independence from the European Coal and Steel Community; he saw this as a Franco-German project and Britain still had an empire. In the General Election of 1951, Labour was defeated.

America’s National Churchill Museum, is located on the Westminster College campus in Fulton, Missouri, United States. The museum commemorates Sir Winston Churchill, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and comprises three elements: the Church of St Mary Aldermanbury, the museum itself, and the Breakthrough sculpture. In 1677, the church had been renovated by English architect Christopher Wren.

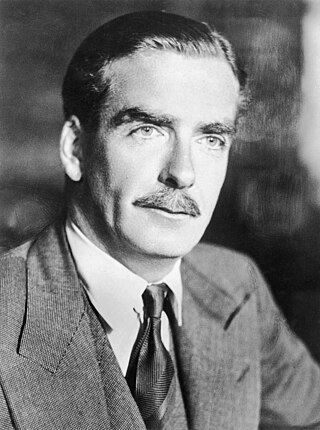

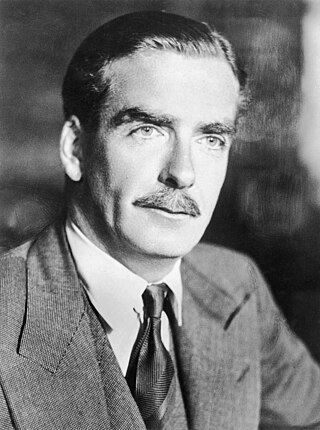

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

The following is a timeline of the first premiership of Winston Churchill, who was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 and again from 1951 to 1955. Churchill served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the bulk of World War II. His speeches and radio broadcasts helped inspire British resistance, especially during the difficult days of 1940–41 when the British Commonwealth and Empire stood almost alone in its active opposition to Nazi Germany. He led Britain as Prime Minister until victory over Nazi Germany had been secured.

The presidency of Harry S. Truman began on April 12, 1945, when Harry S. Truman became the 33rd president upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953.

The UK-US relations in World War II comprised an extensive and highly complex relationship, in terms of diplomacy, military action, financing, and supplies. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt formed close personal ties, that operated apart from their respective diplomatic and military organizations.

When Britain emerged victorious from the Second World War, the Labour Party under Clement Attlee came to power and created a comprehensive welfare state, with the establishment of the National Health Service giving free healthcare to all British citizens, and other reforms to benefits. The Bank of England, railways, heavy industry, and coal mining were all nationalised. Unlike the others, the most controversial issue was nationalisation of steel, which was profitable. Economic recovery was slow, housing was in short supply, and bread was rationed along with many necessities in short supply. It was an "age of austerity". American loans and Marshall Plan grants kept the economy afloat. India, Pakistan, Burma, and Ceylon gained independence. Britain was a strong anti-Soviet factor in the Cold War and helped found NATO in 1949. Many historians describe this era as the "post-war consensus", emphasising how both the Labour and Conservative Parties until the 1970s tolerated or encouraged nationalisation, strong trade unions, heavy regulation, high taxes, and generous welfare state.

Winston Churchill's first address to the U.S. Congress was a 30-minute World War II-era radio-broadcast speech made in the chamber of the United States Senate on December 26, 1941. The prime minister of the United Kingdom addressed a joint meeting of the bicameral legislature of the United States about the state of the UK–U.S. alliance and their prospects for defeating the Axis Powers.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's 1943 address to Congress took place May 19 at 12:30 p.m. EWT before a joint meeting of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, roughly a year and a half after his 1941 speech to the same body. He noted that some 500 days had passed since then, during which the two Allies had been fighting "shoulder to shoulder." Sometimes called Churchill's Fighting Speech, the 55-minute address was made while Churchill and other Allied leaders were in Washington for the Trident Conference, which was organized to plan what became Operation Overlord.

Sure I am that this day, now, we are the masters of our fate. That the task which has been set us is not above our strength. That its pangs and toils are not beyond our endurance. As long as we have faith in our cause, and an unconquerable willpower, salvation will not be denied us.