I make this oath as a member of Korean Patriotic Association to kill the military leaders of the enemy who are invading Korea in order to redeem the independence and freedom of our country.

Hongkou Park Incident

On January 28, 1932, the Japanese army launched an attack on the Chinese National Revolutionary Army's 19th Route Army stationed in Zhabei, Shanghai. After more than a month of resistance, the Chinese forces gradually lost ground and eventually abandoned their positions in Jiangwan and Zhabei, retreating across the entire front. On March 3, after the Japanese occupied Zhenru and Nanxiang, they declared a ceasefire. Subsequently, with the mediation of Britain, the United States, France, and Italy, both sides began negotiations.

During the negotiations, Japanese military and political officials in Shanghai decided to take advantage of the celebration of "Tenchō Setsu" (the birthday of Emperor Shōwa) on April 29 to hold a "Victory Celebration of the Battle of Shanghai" at Hongkou Park, Shanghai..

Against this backdrop, Chen Mingshu, the acting Premier of the Executive Yuan of the Nationalist Government and Commander of the Shanghai Defense Force, along with others, decided to carry out an assassination to disrupt the Japanese celebration. Chen approached his friend Wang Yaqiao, known as the "King of Assassins," and shared this idea with him. Wang expressed his support. However, the Japanese, wary of potential threats, declared that "no Chinese would be allowed to attend the victory celebration," making it difficult to act.

Wang then suggested that the exiled Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, based in Shanghai, be asked to send someone for the task. He contacted Ahn Chang-ho, the Minister of Internal Affairs of the Provisional Government, with whom he had a close relationship, and proposed the plan, offering a sum of 40,000 yuan for funding. Ahn Chang-ho subsequently met with Kim Gu, the Minister of Police of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea at the time. Kim agreed to take on the mission.

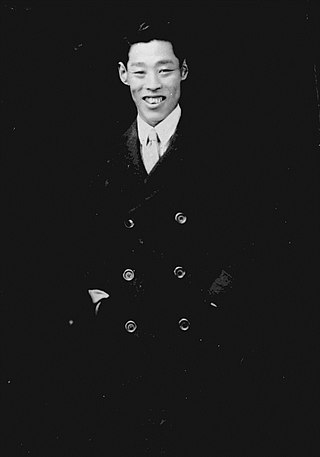

After accepting the mission, Kim Gu, learning from the failure of Lee Bong-chang's attempt to assassinate Emperor Hirohito during the Sakuradamon Incident, meticulously prepared the explosives. At the same time, Kim approached a young Korean exile in Shanghai, Yun Bong-gil, to carry out the assassination. Yun Bong-gil, who was fluent in Japanese and resolute in his determination, immediately agreed to undertake the mission. On April 26, Yun joined the Korean Patriotic Corps and took an oath under the Korean national flag, capturing the moment in a photograph.

On 29 April 1932, Yun took a bomb disguised as a water bottle to a celebration arranged by the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) in honor of Emperor Hirohito's birthday at Hongkou Park. The bomb killed the government minister for Japanese residents in Shanghai, Kawabata Teiji , and mortally wounded General Yoshinori Shirakawa, who died of his injuries on 26 May 1932. [7] [ unreliable source? ] Among the seriously injured were Lieutenant General Kenkichi Ueda, the commander of the 9th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army, and Mamoru Shigemitsu, Japanese Envoy in Shanghai, who each lost a leg, and IJN Admiral Kichisaburō Nomura who lost an eye. The Japanese Consul-General in Shanghai, Kuramatsu Murai (村井倉松), was seriously injured in the head and body. [8]

Yun then tried to kill himself by detonating a second bomb disguised in a bento box.[ citation needed ] It did not explode and he was arrested at the scene. [9]

Sentencing and execution

After being convicted by a Japanese military court in Shanghai on 25 May, he was transferred to Osaka prison on 18 November. He was then moved to Kanazawa, Ishikawa: the headquarters of the IJA's 9th Division. Yun was executed by firing squad on 19 December. [4] His body was buried in Nodayama cemetery in Kanazawa.

Legacy

The then-President of the Chinese Republic, Chiang Kai-shek of the Kuomintang government, praised Yun's actions, stating he was "a young Korean patriot who has accomplished something tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers could not do". [10] [11] [12] However the future South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, disapproved of the incident and Kim Gu's strategy of assassinations as a means to achieve independence because the Japanese could use such attacks to justify their oppression in Korea. [8]

Funeral and honours

In May 1946, Korean residents in Japan exhumed Yun's remains from Nodayama cemetery. After being transferred to Seoul, they were given Korean funeral rites and reburied in Hyochang Park. [13] [14] [15]

On 1 March 1962, the South Korean government posthumously bestowed on him the Republic of Korea Cordon (the highest honor) of the Order of Merit for National Foundation.

On 27 March 1968, Chiang Kai-shek, the president of Republic of China in exile in Taiwan, wrote a prose to applaud Yun's action at the request of Yun's biographer, which was not revealed until 18 Dec 2013. [16]

Memorials

Yun Bong-gil Memorial Hall was built in commemoration of the 55th anniversary of his death. [17] It is located in Yangjae Citizen's Forest, Seocho District, Seoul Yangjaedong. Second name of Yangjae Citizen's Forest Station is 'Maeheon' which is named after his pen name.

There is also a memorial hall called the Plum Pavilion in Lu Xun Park, Shanghai where the bomb throwing incident happened. [18]

In Kanazawa, Ishikawa, Japan, a monument was built on the site where Yun Bong-gil was buried after being executed by the Imperial Japanese Army.

Modern re-evaluation

In South Korea, discussion on whether Yun's bombing attack in 1932 would have been considered terrorism in a modern context is a sensitive issue. In 2007, Anders Karlsson, a visiting Swedish scholar from SOAS, University of London, compared Yun Bong-gil and Kim Gu to terrorists in his lecture on Korean history. His comparison provoked strong criticism from the newspaper JoongAng Ilbo . Prof. Jeong Byeong-jun, interviewed by JoongAng Ilbo, dismissed Karlsson's description as the "view of Westerners". [19] Later, he explained his purpose was to highlight "how the implications of the 'terrorism' have changed over the course of the past century". [20] In 2013, Tessa Morris-Suzuki, an English historian and professor at Australian National University, concurred with Karlsson's explanation and wrote in her academic article, "If we accept the literal dictionary definition of the term terrorists as partisan, member of a resistance organization or guerrilla force using acts of violence then Yoo was self-evidently a terrorist." [20]

On the other hand, at the "International Research Conference in Memory of the 70th Anniversary of Yun Bong-gil & Lee Bong-chang's Patriotic Acts", held on 29 April 2002 in Shanghai, some scholars present pointed out that Yun's patriotic acts have distinct differences from modern day terrorism, which targets civilians. Yun only attacked the Japanese top military and political officials attending the event, and no other civilians were hurt by the bombing. To protect civilians, Yun waited until all the diplomats had left the scene. [21]

In popular culture

Yun is played by Lee Kang-min in the 2019 television series Different Dreams . [22] [23]

See also

Related Research Articles

An Jung-geun, sometimes spelled Ahn Joong-keun, was a Korean independence activist. His baptismal name was Thomas (도마).

Kim Ku, also known by his art name Paekpŏm, was a Korean politician. He was a leader of the Korean independence movement against the Empire of Japan, head of the Korean Provisional Government for multiple terms, and a Korean reunification activist after 1945. Kim is revered in South Korea, where he is widely considered one of the greatest figures in Korean history.

Yesan is a county in South Chungcheong Province, South Korea. Famous people from Yesan include independence fighter Yoon Bong-Gil.

The January 28 incident or Shanghai incident was a conflict between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. It took place in the Shanghai International Settlement which was under international control. Japanese army officers, defying higher authorities, had provoked anti-Japanese demonstrations in the International Settlement following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. On January 18th, five Japanese Buddhists in Shanghai belonging to the Nichiren sect allegedly shouted anti-Chinese, pro-Japanese nationalist slogans in Shanghai. In response, a Chinese mob formed killing one monk and injuring two. In response, the Japanese in Shanghai rioted and burned down a factory, killing two Chinese. Heavy fighting broke out, and China appealed to the League of Nations. A truce was finally reached on May 5, calling for Japanese military withdrawal, and an end to Chinese boycotts of Japanese products. It is seen as the first example of a modern war waged in a large city between two heavily equipped armies and as a preview of what was to come during the Second World War.

Yoshinori Shirakawa was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He died from injuries caused by a bomb set by Korean independence activist Yun Bong-gil in Shanghai.

The Korean Liberation Army, also known as the Korean Restoration Army, was the armed forces of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea. It was established on September 17, 1940, in Chongqing, Republic of China, with significant financial and personnel support from the Kuomintang. It participated in various battles and intelligence activities against the Japanese, including alongside the British Army in India and with the United States in the Eagle Project.

Lu Xun Park, formerly Hongkou (Hongkew) Park, is a municipal park in Hongkou District of Shanghai, China. It is located on 146 East Jiangwan Road, right behind Hongkou Football Stadium. It is bounded by Guangzhong Road to the north, Ouyang Road to the northeast, Tian'ai Road to the southeast, Tian'ai Branch Road to the south, and East Jiangwan Road to the west. The park is named after the Chinese writer Lu Xun, who lived nearby in the last years of his life, and is the location of the tomb of Lu Xun and the Lu Xun Museum. In 1932, Korean nationalist Yun Bong-gil detonated a bomb at the park, killing or injuring several high-ranking figures of the Imperial Japanese military during a celebration of Emperor Hirohito's birthday.

Chi Ch'ŏngch'ŏn, also known as Yi Ch'ŏngch'ŏn, was a Korean independence activist during the period of Japanese rule (1910–1945). He later became a South Korean politician. His name was originally Chi Sŏkgyu, but he took the nom de guerre Chi Ch'ŏngch'ŏn, meaning "Earth and Blue Sky", while leading Korean guerrilla forces against the Japanese. To hide his identity from Japanese forces while conducting military independence activities, he also used the names Chi Taehyŏng, Chi Subong, and Chi Ŭlgyu. His pen name was Paeksan, meaning White Mountain.

The Sakuradamon incident was an unsuccessful assassination attempt against Japanese Emperor Hirohito on January 8, 1932, at the gate Sakuradamon in Tokyo, Empire of Japan.

Lee Bong-chang was a Korean independence activist. In Korea, he is remembered as a martyr due to his participation in the 1932 Sakuradamon incident, in which he attempted to assassinate the Japanese Emperor Hirohito with a grenade.

Kim Bong-Gil is a South Korean football coach and former player.

Hyochang Park (Korean: 효창공원) is a park in Yongsan District, Seoul, South Korea. The park is near Exit 1 of the Hyochang Park station of the Seoul Metropolitan Subway. Popular for leisure and exercise, the park has walking paths, sports facilities, forests, and cherry blossom trees. In 1989, the park was designated a Historic Site of South Korea, and contains the Kim Koo Museum.

Lyuh Woon-hyung, also known by his art name Mongyang, was a Korean independence activist and reunification activist.

Yangjae Citizen's Forest (Korean: 양재시민의숲) is a park in Seocho District, Seoul, South Korea. The park's official name is now Maeheon Citizen's Forest, which it adopted in October 2022.

The Korean Patriotic Organization (Korean: 한인애국단) was a militant organization under the Korean Provisional Government (KPG) and founded in Shanghai, China in 1931. It aimed to assassinate military and government leaders of the Empire of Japan. The group also went by the name Ŭisaenggun.

Kim Hong-il was a Korean independence activist and a general of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Korean War, who later became a diplomat and politician in South Korea. Born in North Pyongan, he did his early schooling in China and Korea, and had a brief career as a teacher before his connections with the nascent Korean independence movement led to his imprisonment. He fled into exile in China in 1918, and served in the Kuomintang's National Revolutionary Army from 1926 to 1948, following which he moved to the newly independent South Korea to join the Republic of Korea Army. He commanded South Korea's I Corps during the first year of the Korean War, and was then sent to Taipei as South Korea's ambassador to the Republic of China, which by then had retreated to Taiwan. His assignment there ultimately lasted nine years. He returned to South Korea in 1960 following the April Revolution which ended the rule of Syngman Rhee, and served briefly as Minister of Foreign Affairs under the Park Chung Hee junta. He ran for the National Assembly, first unsuccessfully in 1960 and 1963, and was then elected in 1967 and became a major figure in the opposition New Democratic Party.

The Hongkou Park Incident was a bombing attack on military and colonial personnel of the Empire of Japan at 11:40 am on April 29, 1932. It occurred at Hongkou Park, Shanghai, Republic of China, during a ceremony that honored the birthday of the Emperor of Japan, Hirohito.

The Korean Revolutionary Army was formed in May 1929, while leaders of the anti-Japanese struggle gathered at the National People's Office on Umahaengho-dong Street in Jilin-si, Manchuria, and formed the National People's Prefecture, the only revolutionary military government in southern Manchuria. It was organized into the prefecture's regular army. Afterwards, it was transferred to the Korean Revolutionary Party, which was organized to support and foster the National People's Prefecture. When the Korean Revolutionary Party became invalid in November 1934, the Korean Revolutionary Army government was established by integrating the administrative organization, the National People's Prefecture, and the military organization, the Korean Revolutionary Army. Meanwhile, between 1930 and 1934, the Korean Independence Army under the Korean Independence Party was active in northern Manchuria.

The Gangdo National People's Association (Korean: 간도국민회) was a group in the Korean independence movement in Manchuria organized in 1914. It was formed in exile during the Japanese occupation of Korea. While focusing on educational movements such as building elementary schools and middle schools, the March 1st Movement in 1919 began full-scale activities.

Yang Se-bong was a Korean independence activist and the commander-in-chief of the Korean Revolutionary Army of the National People's Prefecture, during the Japanese colonial period. General Yang Se-bong has joined several independence organization training and leading resistance fighters against the Japanese military and police in Manchuria and Korea. Yang Se-bong was a leader who was transcendent, who warmly embraced the mistakes of his subordinates and did not criticize them under any circumstances. Yang posthumously received the recipient of the Order of Merit for National Foundation.

References

- ↑ 윤봉길(尹奉吉) [Yun Bong-gil]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- ↑ 윤봉길. terms.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ "March First Movement". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- 1 2 "In memory of Yun Bong-gil and His Bombing in Shanghai". Ministry of Patriots & Veterans Affairs. 29 April 2008.

- ↑ 윤봉길. terms.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ "Yun Bong-gil". World War II Database. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- 1 2 Lee, Bong (2003). The Unfinished War: Korea . Algora Publishing. p. 13.

- ↑ "Peace Talks Postponed.; SHANGHAI BOMBING HALTS PEACE TALKS (Published 1932)". The New York Times. 30 April 1932. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ↑ "韩国临时政府在华二十六年". Beijing Digest. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018.

- ↑ ""尹奉吉之伟业永垂不朽" 蒋介石献诗被公开". 中央日报. 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ↑ "The emotional ties that bind forever". chinadailyasia.com. 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "Hyochang Park, Seoul". Cultural Heritage Administration . Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ↑ 최, 용수 (17 June 2021). 그냥 지나칠 수 없는 '효창공원 다섯 무궁화 이야기'. mediahub.seoul.go.kr (in Korean). Seoul Metropolitan Government . Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ↑ 서울 효창공원 (─孝昌公園) [Hyochang Park in Seoul]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ↑ 백, 성호 (19 December 2013). "윤봉길 길이 빛나리" 장제스 헌시 공개. JoongAng Ilbo.

- ↑ "About Yun Bong-gil".

- ↑ "Naver Knowledge encyclopedia" (in Korean).

- ↑ "Foreign Professor Calls Kim Gu, Yun Bong-gil 'Terrorists': Report". The Marmot's Hole. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- 1 2 Tessa Morris-Suzuki (2013). "Heroes collaborators and survivors: Korean kamikaze pilots and the ghosts of wars in Japan and Korea". ANU Research Publications. hdl:1885/49976.

- ↑ 崔志鹰 (2002). "上海召开"纪念尹奉吉、李奉昌义举70周年国际学术会议"". Contemporary Korea (《当代韩国》) (in Chinese). 02.

尹奉吉的义举不能与当代被世人所谴责的恐怖活动相提并论。现代的恐怖活动是伤害无辜的平民百姓, 制造恐怖的气氛。而尹奉吉的刺杀行动是针对日本侵略者的头目, 是反抗侵略和压迫的正义行动, 他没有伤及任何一个无辜的平民百姓。当时, 尹奉吉为了不伤害无辜, 他冒着被发现的危险, 等到各国外交人员全部离开之后,才扔出炸弹。......义烈斗争并非简单的个人的恐怖行动, 它是韩国独立运动的一种方略, 在当时的历史条件下,是唯一能选择的斗争方式。

- ↑ Lee, Mi-young (22 June 2019). '이몽', 윤봉길 의사 등장…일왕에 폭탄 투척 "뜨거운 하이라이트". inews24 (in Korean). Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ↑ Yoo, Jung-hee (24 June 2019). '이몽', 윤봉길 의사 투탄 의거 재조명…묵직한 울림. The Korea Economic Daily (in Korean). Retrieved 1 September 2021.

External links

Yun Bong-gil | |

|---|---|

Yun in 1932 | |

| Born | 21 June 1908 |

| Died | 19 December 1932 (aged 24) |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Burial place |

|

| Awards | Order of Merit for National Foundation |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 윤봉길 |

| Hanja | 尹奉吉 |

| Revised Romanization | Yun Bonggil |

| McCune–Reischauer | Yun Ponggil |

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |