Related Research Articles

Folate, also known as vitamin B9 and folacin, is one of the B vitamins. Manufactured folic acid, which is converted into folate by the body, is used as a dietary supplement and in food fortification as it is more stable during processing and storage. Folate is required for the body to make DNA and RNA and metabolise amino acids necessary for cell division. As humans cannot make folate, it is required in the diet, making it an essential nutrient. It occurs naturally in many foods. The recommended adult daily intake of folate in the U.S. is 400 micrograms from foods or dietary supplements.

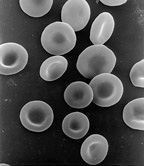

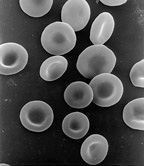

Anemia or anaemia is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, or a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin. The name is derived from Ancient Greek: ἀναιμία anaimia, meaning 'lack of blood', from ἀν- an-, 'not' and αἷμα haima, 'blood'. When anemia comes on slowly, the symptoms are often vague, such as tiredness, weakness, shortness of breath, headaches, and a reduced ability to exercise. When anemia is acute, symptoms may include confusion, feeling like one is going to pass out, loss of consciousness, and increased thirst. Anemia must be significant before a person becomes noticeably pale. Symptoms of anemia depend on how quickly hemoglobin decreases. Additional symptoms may occur depending on the underlying cause. Preoperative anemia can increase the risk of needing a blood transfusion following surgery. Anemia can be temporary or long term and can range from mild to severe.

Pernicious anemia is a disease in which not enough red blood cells are produced due to a deficiency of vitamin B12. Those affected often have a gradual onset. The most common initial symptoms are feeling tired and weak. Other symptoms of anemia may include shortness of breath, lightheadedness, headaches, sore red tongue, cold hands and feet, pale or yellow skin, chest pain, and an irregular heartbeat. The digestive tract may also be disturbed giving symptoms that can include nausea and vomiting, heartburn, upset stomach and loss of appetite. Symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency may include decreased ability to think, numbness in the hands and feet, memory problems, blurred vision, trouble walking, poor balance, muscle weakness, decreased smell and taste, poor reflexes, clumsiness, depression, and confusion. Without treatment, some of these problems may become permanent.

Iron-deficiency anemia is anemia caused by a lack of iron. Anemia is defined as a decrease in the number of red blood cells or the amount of hemoglobin in the blood. When onset is slow, symptoms are often vague such as feeling tired, weak, short of breath, or having decreased ability to exercise. Anemia that comes on quickly often has more severe symptoms, including confusion, feeling like one is going to pass out or increased thirst. Anemia is typically significant before a person becomes noticeably pale. Children with iron deficiency anemia may have problems with growth and development. There may be additional symptoms depending on the underlying cause.

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW), as well as various types thereof, is a measure of the range of variation of red blood cell (RBC) volume that is reported as part of a standard complete blood count. Red blood cells have an average volume of 80-100 femtoliters, but individual cell volumes vary even in healthy blood. Certain disorders, however, cause a significantly increased variation in cell size. Higher RDW values indicate greater variation in size. Normal reference range of RDW-CV in human red blood cells is 11.5–15.4%. If anemia is observed, RDW test results are often used together with mean corpuscular volume (MCV) results to determine the possible causes of the anemia. It is mainly used to differentiate an anemia of mixed causes from an anemia of a single cause.

Megaloblastic anemia is a type of macrocytic anemia. An anemia is a red blood cell defect that can lead to an undersupply of oxygen. Megaloblastic anemia results from inhibition of DNA synthesis during red blood cell production. When DNA synthesis is impaired, the cell cycle cannot progress from the G2 growth stage to the mitosis (M) stage. This leads to continuing cell growth without division, which presents as macrocytosis. Megaloblastic anemia has a rather slow onset, especially when compared to that of other anemias. The defect in red cell DNA synthesis is most often due to hypovitaminosis, specifically vitamin B12 deficiency or folate deficiency. Loss of micronutrients may also be a cause.

Hydrops fetalis or hydrops foetalis is a condition in the fetus characterized by an accumulation of fluid, or edema, in at least two fetal compartments. By comparison, hydrops allantois or hydrops amnion is an accumulation of excessive fluid in the allantoic or amniotic space, respectively.

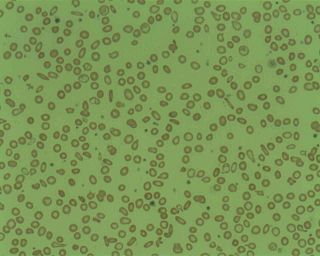

Microcytic anaemia is any of several types of anemia characterized by smaller than normal red blood cells. The normal mean corpuscular volume is approximately 80–100 fL. When the MCV is <80 fL, the red cells are described as microcytic and when >100 fL, macrocytic. The MCV is the average red blood cell size.

Complications of pregnancy are health problems that are related to, or arise during pregnancy. Complications that occur primarily during childbirth are termed obstetric labor complications, and problems that occur primarily after childbirth are termed puerperal disorders. While some complications improve or are fully resolved after pregnancy, some may lead to lasting effects, morbidity, or in the most severe cases, maternal or fetal mortality.

Macrocytosis is the enlargement of red blood cells with near-constant hemoglobin concentration, and is defined by a mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of greater than 100 femtolitres. The enlarged erythrocytes are called macrocytes or megalocytes. As a symptom its cause may be relatively benign and need no treatment or it may indicate a serious underlying illness.

Nutrition and pregnancy refers to the nutrient intake, and dietary planning that is undertaken before, during and after pregnancy. Nutrition of the fetus begins at conception. For this reason, the nutrition of the mother is important from before conception as well as throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding. An ever-increasing number of studies have shown that the nutrition of the mother will have an effect on the child, up to and including the risk for cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and diabetes throughout life.

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are a group of birth defects in which an opening in the spine or cranium remains from early in human development. In the third week of pregnancy called gastrulation, specialized cells on the dorsal side of the embryo begin to change shape and form the neural tube. When the neural tube does not close completely, an NTD develops.

Uterine atony is the failure of the uterus to contract adequately following delivery. Contraction of the uterine muscles during labor compresses the blood vessels and slows flow, which helps prevent hemorrhage and facilitates coagulation. Therefore, a lack of uterine muscle contraction can lead to an acute hemorrhage, as the vasculature is not being sufficiently compressed. Uterine atony is the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage, which is an emergency and potential cause of fatality. Across the globe, postpartum hemorrhage is among the top five causes of maternal death. Recognition of the warning signs of uterine atony in the setting of extensive postpartum bleeding should initiate interventions aimed at regaining stable uterine contraction.

Folate deficiency, also known as vitamin B9 deficiency, is a low level of folate and derivatives in the body. Signs of folate deficiency are often subtle. A low number of red blood cells (anemia) is a late finding in folate deficiency and folate deficiency anemia is the term given for this medical condition. It is characterized by the appearance of large-sized, abnormal red blood cells (megaloblasts), which form when there are inadequate stores of folic acid within the body.

Anisocytosis is a medical term meaning that a patient's red blood cells are of unequal size. This is commonly found in anemia and other blood conditions. False diagnostic flagging may be triggered on a complete blood count by an elevated WBC count, agglutinated RBCs, RBC fragments, giant platelets or platelet clumps. In addition, it is a characteristic feature of bovine blood.

Vitamin B12 deficiency, also known as cobalamin deficiency, is the medical condition in which the blood and tissue have a lower than normal level of vitamin B12. Symptoms can vary from none to severe. Mild deficiency may have few or absent symptoms. In moderate deficiency, feeling tired, anemia, soreness of the tongue, mouth ulcers, breathlessness, feeling faint, rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure, pallor, hair loss, decreased ability to think and severe joint pain and the beginning of neurological symptoms, including abnormal sensations such as pins and needles, numbness and tinnitus may occur. Severe deficiency may include symptoms of reduced heart function as well as more severe neurological symptoms, including changes in reflexes, poor muscle function, memory problems, blurred vision, irritability, ataxia, decreased smell and taste, decreased level of consciousness, depression, anxiety, guilt and psychosis. If left untreated, some of these changes can become permanent. Temporary infertility reversible with treatment, may occur. In exclusively breastfed infants of vegan mothers, undetected and untreated deficiency can lead to poor growth, poor development, and difficulties with movement.

The term macrocytic is from Greek words meaning "large cell". A macrocytic class of anemia is an anemia in which the red blood cells (erythrocytes) are larger than their normal volume. The normal erythrocyte volume in humans is about 80 to 100 femtoliters. In metric terms the size is given in equivalent cubic micrometers. The condition of having erythrocytes which are too large, is called macrocytosis. In contrast, in microcytic anemia, the erythrocytes are smaller than normal.

Normocytic anemia is a type of anemia and is a common issue that occurs for men and women typically over 85 years old. Its prevalence increases with age, reaching 44 percent in men older than 85 years. The most common type of normocytic anemia is anemia of chronic disease.

Anemia is a deficiency in the size or number of red blood cells or in the amount of hemoglobin they contain. This deficiency limits the exchange of O2 and CO2 between the blood and the tissue cells. Globally, young children, women, and older adults are at the highest risk of developing anemia. Anemia can be classified based on different parameters, and one classification depends on whether it is related to nutrition or not so there are two types: nutritional anemia and non-nutritional anemia. Nutritional anemia refers to anemia that can be directly attributed to nutritional disorders or deficiencies. Examples include Iron deficiency anemia and pernicious anemia. It is often discussed in a pediatric context.

Thyroid disease in pregnancy can affect the health of the mother as well as the child before and after delivery. Thyroid disorders are prevalent in women of child-bearing age and for this reason commonly present as a pre-existing disease in pregnancy, or after childbirth. Uncorrected thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy has adverse effects on fetal and maternal well-being. The deleterious effects of thyroid dysfunction can also extend beyond pregnancy and delivery to affect neurointellectual development in the early life of the child. Due to an increase in thyroxine binding globulin, an increase in placental type 3 deioidinase and the placental transfer of maternal thyroxine to the fetus, the demand for thyroid hormones is increased during pregnancy. The necessary increase in thyroid hormone production is facilitated by high human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) concentrations, which bind the TSH receptor and stimulate the maternal thyroid to increase maternal thyroid hormone concentrations by roughly 50%. If the necessary increase in thyroid function cannot be met, this may cause a previously unnoticed (mild) thyroid disorder to worsen and become evident as gestational thyroid disease. Currently, there is not enough evidence to suggest that screening for thyroid dysfunction is beneficial, especially since treatment thyroid hormone supplementation may come with a risk of overtreatment. After women give birth, about 5% develop postpartum thyroiditis which can occur up to nine months afterwards. This is characterized by a short period of hyperthyroidism followed by a period of hypothyroidism; 20–40% remain permanently hypothyroid.

References

- ↑ "Anemia | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Pavord, Sue; Myers, Bethan; Robinson, Susan; Allard, Shubha; Strong, Jane; Oppenheimer, Christina; British Committee for Standards in Haematology (March 2012). "UK guidelines on the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy". British Journal of Haematology. 156 (5): 588–600. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.09012.x. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 22512001. S2CID 12588512.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics (August 2021). "Anemia in Pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 233". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 138 (2): e55–e64. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004477. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 34293770. S2CID 236198933.

- ↑ "Home | National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-25.

- ↑ Breymann, Christian (October 2015). "Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy". Seminars in Hematology. 52 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2015.07.003. ISSN 1532-8686. PMID 26404445.

- 1 2 Sifakis, S.; Pharmakides, G. (2000). "Anemia in Pregnancy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 900 (1): 125–136. Bibcode:2000NYASA.900..125S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06223.x. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 10818399. S2CID 6740558.

- 1 2 3 "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ↑ Flessa, H. C. (December 1974). "Hemorrhagic disorders and pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 17 (4): 236–249. doi:10.1097/00003081-197412000-00015. ISSN 0009-9201. PMID 4615860.

- 1 2 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics (2021-08-01). "Anemia in Pregnancy: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 233". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 138 (2): e55–e64. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004477. ISSN 1873-233X. PMID 34293770. S2CID 236198933.

- ↑ Campbell, B. A. (September 1995). "Megaloblastic anemia in pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38 (3): 455–462. doi:10.1097/00003081-199509000-00005. ISSN 0009-9201. PMID 8612357.

- ↑ Parrott, Julie; Frank, Laura; Rabena, Rebecca; Craggs-Dino, Lillian; Isom, Kellene A.; Greiman, Laura (May 2017). "American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 13 (5): 727–741. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018. ISSN 1878-7533. PMID 28392254.

- ↑ "Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Green, S. T.; Ng, J. P. (1986). "Hypothyroidism and anaemia". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 40 (9): 326–331. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 3828479.

- ↑ "Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Harrison, Rachel K.; Lauhon, Samantha R.; Colvin, Zachary A.; McIntosh, Jennifer J. (September 2021). "Maternal anemia and severe maternal morbidity in a US cohort". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM. 3 (5): 100395. doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100395 . PMC 8435012 . PMID 33992832.

- ↑ Geng, Fengji; Mai, Xiaoqin; Zhan, Jianying; Xu, Lin; Zhao, Zhengyan; Georgieff, Michael; Shao, Jie; Lozoff, Betsy (December 2015). "Impact of Fetal-Neonatal Iron Deficiency on Recognition Memory at 2 Months of Age". The Journal of Pediatrics. 167 (6): 1226–1232. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.035. ISSN 1097-6833. PMC 4662910 . PMID 26382625.

- ↑ Beard, John L. (December 2008). "Why iron deficiency is important in infant development". The Journal of Nutrition. 138 (12): 2534–2536. doi:10.1093/jn/138.12.2534. ISSN 1541-6100. PMC 3415871 . PMID 19022985.

- ↑ Lozoff, Betsy; Beard, John; Connor, James; Barbara, Felt; Georgieff, Michael; Schallert, Timothy (May 2006). "Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy". Nutrition Reviews. 64 (5 Pt 2): S34–43, discussion S72–91. doi:10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43. ISSN 0029-6643. PMC 1540447 . PMID 16770951.

- 1 2 3 Pavord, Sue; Daru, Jan; Prasannan, Nita; Robinson, Susan; Stanworth, Simon; Girling, Joanna; BSH Committee (March 2020). "UK guidelines on the management of iron deficiency in pregnancy". British Journal of Haematology. 188 (6): 819–830. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16221 . ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 31578718. S2CID 203652784.

- ↑ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- ↑ "Iron-deficiency anemia". womenshealth.gov. 2017-02-17. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ↑ Jansen, A. J. G.; van Rhenen, D. J.; Steegers, E. a. P.; Duvekot, J. J. (October 2005). "Postpartum hemorrhage and transfusion of blood and blood components". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 60 (10): 663–671. doi:10.1097/01.ogx.0000180909.31293.cf. ISSN 0029-7828. PMID 16186783. S2CID 1910601.

- ↑ Roy, N. B. A.; Pavord, S. (April 2018). "The management of anaemia and haematinic deficiencies in pregnancy and post-partum". Transfusion Medicine (Oxford, England). 28 (2): 107–116. doi:10.1111/tme.12532. ISSN 1365-3148. PMID 29744977. S2CID 13665022.

- ↑ Sifakis, S.; Pharmakides, G. (2006-01-25). "Anemia in Pregnancy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 900 (1): 125–136. Bibcode:2000NYASA.900..125S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06223.x. PMID 10818399. S2CID 6740558.

- 1 2 "Recommendations to Prevent and Control Iron Deficiency in the United States". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ "Anemia and Pregnancy". www.hematology.org. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- 1 2 3 Achebe, Maureen M.; Gafter-Gvili, Anat (2017-02-23). "How I treat anemia in pregnancy: iron, cobalamin, and folate". Blood. 129 (8): 940–949. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-672246 . ISSN 1528-0020. PMID 28034892.

- ↑ "Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports. 47 (RR-3): 1–29. 1998-04-03. ISSN 1057-5987. PMID 9563847.

- ↑ Juul, Sandra E.; Derman, Richard J.; Auerbach, Michael (2019). "Perinatal Iron Deficiency: Implications for Mothers and Infants". Neonatology. 115 (3): 269–274. doi: 10.1159/000495978 . ISSN 1661-7819. PMID 30759449.

- ↑ Markova, Veronika; Norgaard, Astrid; Jørgensen, Karsten Juhl; Langhoff-Roos, Jens (2015-08-13). "Treatment for women with postpartum iron deficiency anaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (8): CD010861. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010861.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8741208 . PMID 26270434.

- ↑ Dahlke, Joshua D.; Mendez-Figueroa, Hector; Maggio, Lindsay; Hauspurg, Alisse K.; Sperling, Jeffrey D.; Chauhan, Suneet P.; Rouse, Dwight J. (July 2015). "Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage: a comparison of 4 national guidelines". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (1): 76.e1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.023. ISSN 1097-6868. PMID 25731692.

- ↑ Shaylor, Ruth; Weiniger, Carolyn F.; Austin, Naola; Tzabazis, Alexander; Shander, Aryeh; Goodnough, Lawrence T.; Butwick, Alexander J. (January 2017). "National and International Guidelines for Patient Blood Management in Obstetrics: A Qualitative Review". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 124 (1): 216–232. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001473. ISSN 1526-7598. PMC 5161642 . PMID 27557476.

- ↑ "Preconception care to reduce maternal and childhood mortality and morbidity". www.who.int. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Stephen, Grace; Mgongo, Melina; Hussein Hashim, Tamara; Katanga, Johnson; Stray-Pedersen, Babill; Msuya, Sia Emmanueli (2018-05-02). "Anaemia in Pregnancy: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Adverse Perinatal Outcomes in Northern Tanzania". Anemia. 2018: 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2018/1846280 . PMC 5954959 . PMID 29854446.