Related Research Articles

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is an infection of the vagina caused by excessive growth of bacteria. Common symptoms include increased vaginal discharge that often smells like fish. The discharge is usually white or gray in color. Burning with urination may occur. Itching is uncommon. Occasionally, there may be no symptoms. Having BV approximately doubles the risk of infection by a number of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS. It also increases the risk of early delivery among pregnant women.

The human microbiome is the aggregate of all microbiota that reside on or within human tissues and biofluids along with the corresponding anatomical sites in which they reside, including the gastrointestinal tract, skin, mammary glands, seminal fluid, uterus, ovarian follicles, lung, saliva, oral mucosa, conjunctiva, and the biliary tract. Types of human microbiota include bacteria, archaea, fungi, protists, and viruses. Though micro-animals can also live on the human body, they are typically excluded from this definition. In the context of genomics, the term human microbiome is sometimes used to refer to the collective genomes of resident microorganisms; however, the term human metagenome has the same meaning.

Vaginitis, also known as vulvovaginitis, is inflammation of the vagina and vulva. Symptoms may include itching, burning, pain, discharge, and a bad smell. Certain types of vaginitis may result in complications during pregnancy.

Prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM), previously known as premature rupture of membranes, is breakage of the amniotic sac before the onset of labor. Women usually experience a painless gush or a steady leakage of fluid from the vagina. Complications in the baby may include premature birth, cord compression, and infection. Complications in the mother may include placental abruption and postpartum endometritis.

Vaginal discharge is a mixture of liquid, cells, and bacteria that lubricate and protect the vagina. This mixture is constantly produced by the cells of the vagina and cervix, and it exits the body through the vaginal opening. The composition, amount, and quality of discharge varies between individuals and can vary throughout the menstrual cycle and throughout the stages of sexual and reproductive development. Normal vaginal discharge may have a thin, watery consistency or a thick, sticky consistency, and it may be clear or white in color. Normal vaginal discharge may be large in volume but typically does not have a strong odor, nor is it typically associated with itching or pain. While most discharge is considered physiologic or represents normal functioning of the body, some changes in discharge can reflect infection or other pathological processes. Infections that may cause changes in vaginal discharge include vaginal yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, and sexually transmitted infections. The characteristics of abnormal vaginal discharge vary depending on the cause, but common features include a change in color, a foul odor, and associated symptoms such as itching, burning, pelvic pain, or pain during sexual intercourse.

Levilactobacillus brevis is a gram-positive, rod shaped species of lactic acid bacteria which is heterofermentative, creating CO2, lactic acid and acetic acid or ethanol during fermentation. L. brevis is the type species of the genus Levilactobacillus (previously L. brevis group), which comprises 24 species. It can be found in many different environments, such as fermented foods, and as normal microbiota. L. brevis is found in food such as sauerkraut and pickles. It is also one of the most common causes of beer spoilage. Ingestion has been shown to improve human immune function, and it has been patented several times. Normal gut microbiota L. brevis is found in human intestines, vagina, and feces.

Fusobacterium nucleatum is a Gram-negative, anaerobic oral bacterium, commensal to the human oral cavity, that plays a role in periodontal disease. This organism is commonly recovered from different monocultured microbial and mixed infections in humans and animals. In health and disease, it is a key component of periodontal plaque due to its abundance and its ability to coaggregate with other bacteria species in the oral cavity.

Vaginal flora, vaginal microbiota or vaginal microbiome are the microorganisms that colonize the vagina. They were discovered by the German gynecologist Albert Döderlein in 1892 and are part of the overall human flora. The amount and type of bacteria present have significant implications for an individual's overall health. The primary colonizing bacteria of a healthy individual are of the genus Lactobacillus, such as L. crispatus, and the lactic acid they produce is thought to protect against infection by pathogenic species.

A cervical mucus plug (operculum) is a plug that fills and seals the cervical canal during pregnancy. It is formed by a small amount of cervical mucus that condenses to form a cervical mucus plug during pregnancy.

A douche is a device used to introduce a stream of water into the body for medical or hygienic reasons, or the stream of water itself. Douche usually refers to vaginal irrigation, the rinsing of the vagina, but it can also refer to the rinsing of any body cavity. A douche bag is a piece of equipment for douching—a bag for holding the fluid used in douching. To avoid transferring intestinal bacteria into the vagina, the same bag must not be used for an enema and a vaginal douche.

Prevotella is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria.

Vaginal yeast infection, also known as candidal vulvovaginitis and vaginal thrush, is excessive growth of yeast in the vagina that results in irritation. The most common symptom is vaginal itching, which may be severe. Other symptoms include burning with urination, a thick, white vaginal discharge that typically does not smell bad, pain during sex, and redness around the vagina. Symptoms often worsen just before a woman's period.

The Human Microbiome Project (HMP), completed in 2012, laid the foundation for further investigation into the role the microbiome plays in overall health and disease. One area of particular interest is the role which delivery mode plays in the development of the infant/neonate microbiome and what potential implications this may have long term. It has been found that infants born via vaginal delivery have microbiomes closely mirroring that of the mother's vaginal microbiome, whereas those born via cesarean section tend to resemble that of the mother's skin. One notable study from 2010 illustrated an abundance of Lactobacillus and other typical vaginal genera in stool samples of infants born via vaginal delivery and an abundance of Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium, commonly found on the skin surfaces, in stool samples of infants born via cesarean section. From these discoveries came the concept of vaginal seeding, also known as microbirthing, which is a procedure whereby vaginal fluids are applied to a new-born child delivered by caesarean section. The idea of vaginal seeding was explored in 2015 after Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello discovered that birth by caesarean section significantly altered the newborn child's microbiome compared to that of natural birth. The purpose of the technique is to recreate the natural transfer of bacteria that the baby gets during a vaginal birth. It involves placing swabs in the mother's vagina, and then wiping them onto the baby's face, mouth, eyes and skin. Due to the long-drawn nature of studying the impact of vaginal seeding, there are a limited number of studies available that support or refute its use. The evidence suggests that applying microbes from the mother's vaginal canal to the baby after cesarean section may aid in the partial restoration of the infant's natural gut microbiome with an increased likelihood of pathogenic infection to the child via vertical transmission.

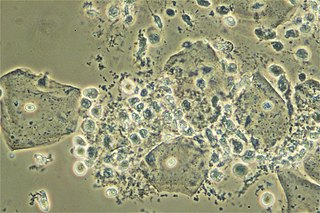

Aerobic vaginitis (AV) is a form of vaginitis first described by Donders et al. in 2002. It is characterized by a more or less severe disruption of the lactobacillary flora, along with inflammation, atrophy, and the presence of a predominantly aerobic microflora, composed of enteric commensals or pathogens.

The placental microbiome is the nonpathogenic, commensal bacteria claimed to be present in a healthy human placenta and is distinct from bacteria that cause infection and preterm birth in chorioamnionitis. Until recently, the healthy placenta was considered to be a sterile organ but now genera and species have been identified that reside in the basal layer.

The uterine microbiome is the commensal, nonpathogenic, bacteria, viruses, yeasts/fungi present in a healthy uterus, amniotic fluid and endometrium and the specific environment which they inhabit. It has been only recently confirmed that the uterus and its tissues are not sterile. Due to improved 16S rRNA gene sequencing techniques, detection of bacteria that are present in low numbers is possible. Using this procedure that allows the detection of bacteria that cannot be cultured outside the body, studies of microbiota present in the uterus are expected to increase.

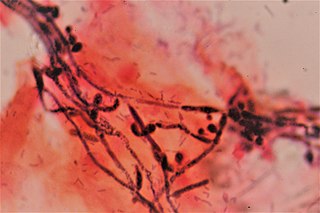

Lactobacillus vaccines are used in the therapy and prophylaxis of non-specific bacterial vaginitis and trichomoniasis. The vaccines consist of specific inactivated strains of Lactobacilli, called "aberrant" strains in the relevant literature dating from the 1980s. These strains were isolated from the vaginal secretions of patients with acute colpitis. The lactobacilli in question are polymorphic, often shortened or coccoid in shape and do not produce an acidic, anti-pathogenic vaginal environment. A colonization with aberrant lactobacilli has been associated with an increased susceptibility to vaginal infections and a high rate of relapse following antimicrobial treatment. Intramuscular administration of inactivated aberrant lactobacilli provokes a humoral immune response. The production of specific antibodies both in serum and in the vaginal secretion has been demonstrated. As a result of the immune stimulation, the abnormal lactobacilli are inhibited, the population of normal, rod-shaped lactobacilli can grow and exert its defense functions against pathogenic microorganisms.

References

- ↑ Africa, Charlene; Nel, Janske; Stemmet, Megan (2014). "Anaerobes and Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy: Virulence Factors Contributing to Vaginal Colonisation". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (7): 6979–7000. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110706979 . ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4113856 . PMID 25014248.

- ↑ Lamont, RF; Sobel, JD; Akins, RA; Hassan, SS; Chaiworapongsa, T; Kusanovic, JP; Romero, R (2011). "The vaginal microbiome: new information about genital tract flora using molecular based techniques". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 118 (5): 533–549. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02840.x. ISSN 1470-0328. PMC 3055920 . PMID 21251190.

- 1 2 Petrova, Mariya I.; Lievens, Elke; Malik, Shweta; Imholz, Nicole; Lebeer, Sarah (2015). "Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health". Frontiers in Physiology. 6: 81. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00081 . ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 4373506 . PMID 25859220.

- ↑ Unlu, Cihat; Donders, Gilbert (2011). "Use of lactobacilli and estriol combination in the treatment of disturbed vaginal ecosystem: a review". Journal of the Turkish German Gynecological Association. 12 (4): 239–246. doi:10.5152/jtgga.2011.57. ISSN 1309-0399. PMC 3939257 . PMID 24592002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gupta, Parakriti; Singh, Mini P.; Goyal, Kapil (July 24, 2020). "Diversity of Vaginal Microbiome in Pregnancy: Deciphering the Obscurity". Frontiers in Public Health. 8: 326. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00326 . PMC 7393601 . PMID 32793540.

- 1 2 3 Wang, Weihong; Hao, Jiatao; An, Ruifang. "Abnormal vaginal flora correlates with pregnancy outcomes: A retrospective study from 737 pregnant women". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology.

- ↑ Perez-Muñoz, Maria Elisa; Arrieta, Marie-Claire; Ramer-Tait, Amanda E.; Walter, Jens (2017). "A critical assessment of the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome". Microbiome. 5 (1): 48. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4 . ISSN 2049-2618. PMC 5410102 . PMID 28454555.