Derivation

The circumradius of the horizontal circumcircle of the regular  -gon at the base is

-gon at the base is

The vertices at the base are at

the vertices at the top are at

Via linear interpolation, points on the outer triangular edges of the antiprism that connect vertices at the bottom with vertices at the top are at

and at

By building the sums of the squares of the  and

and  coordinates in one of the previous two vectors, the squared circumradius of this section at altitude

coordinates in one of the previous two vectors, the squared circumradius of this section at altitude  is

is

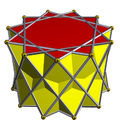

The horizontal section at altitude  above the base is a

above the base is a  -gon (truncated

-gon (truncated  -gon) with

-gon) with  sides of length

sides of length  alternating with

alternating with  sides of length

sides of length  . (These are derived from the length of the difference of the previous two vectors.) It can be dissected into

. (These are derived from the length of the difference of the previous two vectors.) It can be dissected into  isoceless triangles of edges

isoceless triangles of edges  and

and  (semiperimeter

(semiperimeter  ) plus

) plus  isoceless triangles of edges

isoceless triangles of edges  and

and  (semiperimeter

(semiperimeter  ). According to Heron's formula the areas of these triangles are

). According to Heron's formula the areas of these triangles are

and

The area of the section is  , and the volume is

, and the volume is

The volume of a right n-gonal prism with the same l and h is:  which is smaller than that of an antiprism.

which is smaller than that of an antiprism.