Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family Otariidae. They are much more closely related to sea lions than true seals, and share with them external ears (pinnae), relatively long and muscular foreflippers, and the ability to walk on all fours. They are marked by their dense underfur, which made them a long-time object of commercial hunting. Eight species belong to the genus Arctocephalus and are found primarily in the Southern Hemisphere, while a ninth species also sometimes called fur seal, the Northern fur seal, belongs to a different genus and inhabits the North Pacific. The fur seals in Arctocephalus are more closely related to sea lions than they are to the Northern fur seal, but all three groups are more closely related to each other than they are to true seals.

The great white shark, also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major oceans. It is the only known surviving species of its genus Carcharodon. The great white shark is notable for its size, with the largest preserved female specimen measuring 5.83 m (19.1 ft) in length and around 2,000 kg (4,410 lb) in weight at maturity. However, most are smaller; males measure 3.4 to 4.0 m, and females measure 4.6 to 4.9 m on average. According to a 2014 study, the lifespan of great white sharks is estimated to be as long as 70 years or more, well above previous estimates, making it one of the longest lived cartilaginous fishes currently known. According to the same study, male great white sharks take 26 years to reach sexual maturity, while the females take 33 years to be ready to produce offspring. Great white sharks can swim at speeds of 25 km/h (16 mph) for short bursts and to depths of 1,200 m (3,900 ft).

An eared seal, otariid, or otary is any member of the marine mammal family Otariidae, one of three groupings of pinnipeds. They comprise 15 extant species in seven genera and are commonly known either as sea lions or fur seals, distinct from true seals (phocids) and the walrus (odobenids). Otariids are adapted to a semiaquatic lifestyle, feeding and migrating in the water, but breeding and resting on land or ice. They reside in subpolar, temperate, and equatorial waters throughout the Pacific and Southern Oceans, the southern Indian, and Atlantic Oceans. They are conspicuously absent in the north Atlantic.

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. The sea lions have six extant and one extinct species in five genera. Their range extends from the subarctic to tropical waters of the global ocean in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, with the notable exception of the northern Atlantic Ocean. They have an average lifespan of 20–30 years. A male California sea lion weighs on average about 300 kg (660 lb) and is about 2.4 m (8 ft) long, while the female sea lion weighs 100 kg (220 lb) and is 1.8 m (6 ft) long. The largest sea lions are Steller's sea lions, which can weigh 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) and grow to a length of 3.0 m (10 ft). Sea lions consume large quantities of food at a time and are known to eat about 5–8% of their body weight at a single feeding. Sea lions can move around 16 knots in water and at their fastest they can reach a speed of about 30 knots. Three species, the Australian sea lion, the Galápagos sea lion and the New Zealand sea lion, are listed as endangered.

The blue shark, also known as the great blue shark, is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae, which inhabits deep waters in the world's temperate and tropical oceans. Averaging around 3.1 m (10 ft) and preferring cooler waters, the blue shark migrates long distances, such as from New England to South America. It is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

The grey seal is a large seal of the family Phocidae, which are commonly referred to as "true seals" or "earless seals". The only species classified in the genus Halichoerus, it is found on both shores of the North Atlantic Ocean. In Latin, Halichoerus grypus means "hook-nosed sea pig". Its name is spelled gray seal in the US; it is also known as Atlantic seal and the horsehead seal.

The leopard seal, also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic. Its only natural predator is the orca. It feeds on a wide range of prey including cephalopods, other pinnipeds, krill, fish, and birds, particularly penguins. It is the only species in the genus Hydrurga. Its closest relatives are the Ross seal, the crabeater seal and the Weddell seal, which together are known as the tribe of Lobodontini seals. The name hydrurga means "water worker" and leptonyx is the Greek for "thin-clawed".

The Antarctic fur seal is one of eight seals in the genus Arctocephalus, and one of nine fur seals in the subfamily Arctocephalinae. Despite what its name suggests, the Antarctic fur seal is mostly distributed in Subantarctic islands and its scientific name is thought to have come from the German vessel SMS Gazelle, which was the first to collect specimens of this species from Kerguelen Islands.

The subantarctic fur seal is a species of arctocephaline found in the southern parts of the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans. It was first described by Gray in 1872 from a specimen recovered in northern Australia—hence the inappropriate specific name tropicalis.

The Guadalupe fur seal is one of eight members of the fur seal genus Arctocephalus. They are the northernmost member of this genus. Sealers reduced the population to just a few dozen by the late 19th century, but the species had recovered to 10,000 in number by the late 1990s. Many individuals can be found on Mexico's Guadalupe Island.

The Juan Fernández fur seal is the second smallest of the fur seals, second only to the Galápagos fur seal. They are found only on the Pacific Coast of South America, more specifically on the Juan Fernández Islands and the Desventuradas Islands. There is still much that is unknown about this species. Scientists still do not know the average life span of this species, or the diet and behavior of males apart from the breeding season.

The Galápagos fur seal is one of eight seals in the genus Arctocephalus. It is the smallest of all eared seals. It is endemic to the Galápagos Islands in the eastern Pacific. The total estimated population as of 1970 was said to be about 30,000, although the population has been said to be on the decline since the 1980s due to environmental factors such as pollution, disease, invasive species, and their limited territory. Due to the population having been historically vulnerable to hunting, the Galápagos fur seal has been protected by the Ecuadorian government since 1934

The South American sea lion, also called the southern sea lion and the Patagonian sea lion, is a sea lion found on the western and southeastern coasts of South America. It is the only member of the genus Otaria. The species is highly sexually dimorphic. Males have a large head and prominent mane. They mainly feed on fish and cephalopods and haul out on sand, gravel, rocky, or pebble beaches. In most populations, breeding males are both territorial and harem holding; they establish territories first and then try to herd females into them. The overall population of the species is considered stable, estimated at 265,000 animals.

The Australian sea lion, also known as the Australian sea-lion or Australian sealion, is a species of sea lion that is the only endemic pinniped in Australia. It is currently monotypic in the genus Neophoca, with the extinct Pleistocene New Zealand sea lion Neophoca palatina the only known congener. With a population estimated at 14,730 animals, the Wildlife Conservation Act of Western Australia (1950) has listed them as "in need of special protection". Their Conservation status is listed as endangered. These pinnipeds are specifically known for their abnormal breeding cycles, which are varied between a 5-month breeding cycle and a 17-18 month aseasonal breeding cycle, compared to other pinnipeds which fit into a 12-month reproductive cycle. Females are either silver or fawn with a cream underbelly and males are dark brown with a yellow mane and are bigger than the females.

Arctocephalus forsteri is a species of fur seal found mainly around southern Australia and New Zealand. The name New Zealand fur seal is used by English speakers in New Zealand; kekeno is used in the Māori language. As of 2014, the common name long-nosed fur seal has been proposed for the population of seals inhabiting Australia.

The South American fur seal breeds on the coasts of Peru, Chile, the Falkland Islands, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. The total population is around 250,000. However, population counts are sparse and outdated. Although Uruguay has long been considered to be the largest population of South American fur seals, recent census data indicates that the largest breeding population of A. a. australis are at the Falkland Islands followed by Uruguay. The population of South American fur seals in 1999 was estimated at 390,000, a drop from a 1987 estimate of 500,000 - however a paucity of population data, combined with inconsistent census methods, makes it difficult to interpret global population trends.

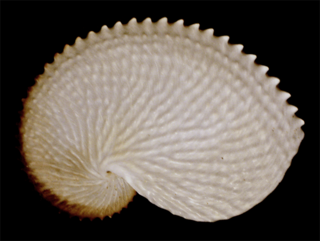

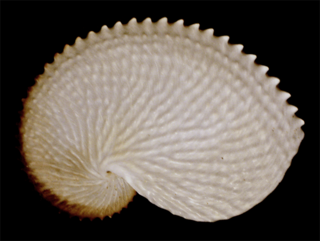

Argonauta nodosus [previously known as Argonauta nodosa], also known as the knobby or knobbed argonaut, is a species of pelagic octopus. The female of the species, like all argonauts, creates a paper-thin eggcase that coils around the octopus much like the way a nautilus lives in its shell. The shell is usually approximately 150 mm in length, although it can exceed 250 mm in exceptional specimens; the world record size is 292.0 mm. A. nodosus produces a very characteristic shell, which is covered in many small nodules on the ridges across the shell, hence the specific epithet nodosus and common name. These nodules are less obvious or even absent in juvenile females, especially those under 5 cm in length. All other argonaut species have smooth ridges across the shell walls.

The puffadder shyshark, also known as the Happy Eddie, is a species of catshark, belonging to the family Scyliorhinidae, endemic to the temperate waters off the coast of South Africa. This common shark is found on or near the bottom in sandy or rocky habitats, from the intertidal zone to a depth of 130 m (430 ft). Typically reaching 60 cm (24 in) in length, the puffadder shyshark has a slender, flattened body and head. It is strikingly patterned with a series of dark-edged, bright orange "saddles" and numerous small white spots over its back. The Natal shyshark, formally described in 2006, was once considered to be an alternate form of the puffadder shyshark.

Enteroctopus magnificus, also known as the southern giant octopus, is a large octopus in the genus Enteroctopus. It is native to the waters off Namibia and South Africa.

Cynoglossus capensis, commonly known as the sand tonguesole, is a species of tonguefish.