The chin is the forward pointed part of the anterior mandible (mental region) below the lower lip. A fully developed human skull has a chin of between 0.7 cm and 1.1 cm.

The chin is the forward pointed part of the anterior mandible (mental region) below the lower lip. A fully developed human skull has a chin of between 0.7 cm and 1.1 cm.

The presence of a well-developed chin is considered to be one of the morphological characteristics of Homo sapiens that differentiates them from other human ancestors such as the closely related Neanderthals. [1] [2] Early human ancestors have varied symphysial morphology, but none of them have a well-developed chin. The origin of the chin is traditionally associated with the anterior–posterior breadth shortening of the dental arch or tooth row; however, its general mechanical or functional advantage during feeding, developmental origin, and link with human speech, physiology, and social influence are highly debated.

Robinson (1913) [3] suggests that the demand to resist masticatory stresses triggered bone thickening in the mental region of the mandible and ultimately formed a prominent chin. Moreover, Daegling (1993) [4] explains the chin as a functional adaptation to resist masticatory stress that causes vertical bending stresses in the coronal plane. Others have argued that the prominent chin is adapted to resisting wishboning forces, [5] dorso-ventral shear forces, and generally a mechanical advantage to resist lateral transverse bending and vertical bending in the coronal plane. [6] On the contrary, others [7] have suggested that the presence of the chin is not related to mastication. The presence of thick bone in the relatively small mandible may indicate better force resistance capacity. However, the question stands of whether the chin is an adaptive or nonadaptive structure.

Recent works on the morphological changes of the mandible during development [8] [9] [10] have shown that the human chin, or at least the inverted-T shaped mental region, develops during the prenatal period, but the chin does not become prominent until the early postnatal period. This later modification happens by bone remodeling processes (bone resorption and bone deposition). [11] Coquerelle et al. [9] [10] show that the anteriorly positioned cervical column of the spine and forward displacement of the hyoid bone limit the anterior–posterior breadth in the oral cavity for the tongue, laryngeal, and suprahyoid musculatures. Accordingly, this leads the upper parts of the mandible (alveolar process) to retract posteriorly, following the posterior movement of the upper tooth row, while the lower part of the symphysis remained protruded to create more space, thereby creating the inverted-T shaped mental relief during early ages and the prominent chin later. The alveolar region (upper or superior part of the symphysis) is sculpted by bone resorption, but the chin (lower or inferior part) is depository in its nature. [11] These coordinated bone growth and modeling processes mold the vertical symphysis present at birth into the prominent shape of the chin.

Recent research on the development of the chin [12] suggests that the evolution of this unique characteristic was formed not by mechanical forces such as chewing but by evolutionary adaptations involving reduction in size and change in shape of the face. Holton et al. claim that this adaptation occurred as the face became smaller compared to that of other ancient humans.

Robert Franciscus takes a more anthropological viewpoint: he believes that the chin was formed as a consequence of the change in lifestyle humans underwent approximately 80,000 years ago. As humans' hunter-gatherer societies grew into larger social networks, territorial disputes decreased because the new social structure promoted building alliances in order to exchange goods and belief systems. Franciscus believes that this change in the human environment reduced hormone levels, especially in men, resulting in the natural evolution of the chin. [13]

Overall, human beings are unique in the sense that they are the only species among primates who have chins. In the paper The Enduring Puzzle of the Human Chin, evolutionary anthropologists James Pampush and David Daegling discuss various theories that have been raised to solve the puzzle of the chin. They conclude that "each of the proposals we have discussed falter either empirically or theoretically; some fail, to a degree, on both accounts… This should serve as motivation, not discouragement, for researchers to continue investigating this modern human peculiarity… perhaps understanding the chin will reveal some unexpected insight into what it means to be human." [14]

The terms cleft chin, [15] chin cleft, [15] [16] dimple chin, [17] [18] or chin dimple [15] refer to a dimple on the chin. It is a Y-shaped fissure on the chin with an underlying bony peculiarity. [19] Specifically, the chin fissure follows the fissure in the lower jaw bone that resulted from the incomplete fusion of the left and right halves of the jaw bone, or muscle, during the embryonal and fetal development. It can also develop during the later mandibular symphysis, due to growth of the mental protuberance during puberty, or as a result of acromegaly. In some cases, one mental tubercle may grow more than another, which can cause facial asymmetry. [15]

A cleft chin is an inherited trait in humans and can be influenced by many factors. The cleft chin is also a classic example of variable penetrance [20] with environmental factors or a modifier gene possibly affecting the phenotypical expression of the actual genotype. Cleft chins can be presented in a child when neither parent presents a cleft chin. Cleft chins are common among people originating from Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. [21]

There is a possible genetic cause for cleft chins, a genetic marker called rs11684042, which is located in chromosome 2. [22]

In Persian literature, the chin dimple is considered a factor of beauty and is metaphorically referred to as "the chin pit" or "the chin well": a well in which the poor lover is fallen and trapped. [23]

A double chin is a loss of definition of the jawbone or soft tissue under the chin. There are two possible causes for a double chin, which have to be differentiated.

In overweight people, commonly the layer of subcutaneous fat around the neck sags down and creates a wrinkle, creating the appearance of a second chin. This fat pad is occasionally surgically removed and the corresponding muscles under the jaw shortened (hyoid lift). [24]

Another cause can be a bony deficiency, commonly seen in people of normal weight. When the jaw bones (mandible and by extension the maxilla) do not project forward enough, the chin in turn will not project forward enough to give the impression of a defined jawline and chin. Despite low amounts of fat in the area, it can appear as if the chin is melting into the neck. The extent of this deficiency can vary drastically and usually has to be treated surgically.[ citation needed ] In some patients, the aesthetic deficit can be overcome with genioplasty alone, in others the lack of forward growth might warrant orthognathic surgery to move one or two jaws forward. If the patient suffers from sleep apnea, early maxillomandibular advancement is usually the only causal treatment and necessary to preserve normal life expectancy.

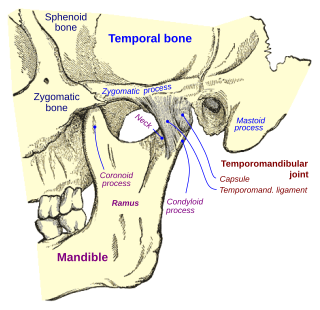

In anatomy, the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) are the two joints connecting the jawbone to the skull. It is a bilateral synovial articulation between the temporal bone of the skull above and the mandible below; it is from these bones that its name is derived. The joints are unique in their bilateral function, being connected via the mandible.

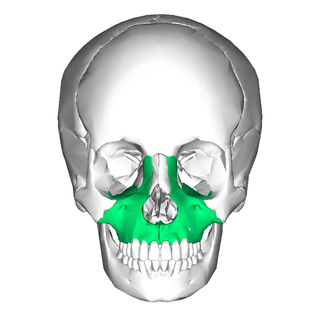

In vertebrates, the maxilla is the upper fixed bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxillary bones are fused at the intermaxillary suture, forming the anterior nasal spine. This is similar to the mandible, which is also a fusion of two mandibular bones at the mandibular symphysis. The mandible is the movable part of the jaw.

Meganthropus is an extinct genus of non-hominin hominid ape, known from the Pleistocene of Indonesia. It is known from a series of large jaw and skull fragments found at the Sangiran site near Surakarta in Central Java, Indonesia, alongside several isolated teeth. The genus has a long and convoluted taxonomic history. The original fossils were ascribed to a new species, Meganthropus palaeojavanicus, and for a long time was considered invalid, with the genus name being used as an informal name for the fossils.

The digastric muscle is a bilaterally paired suprahyoid muscle located under the jaw. Its posterior belly is attached to the mastoid notch of temporal bone, and its anterior belly is attached to the digastric fossa of mandible; the two bellies are united by an intermediate tendon which is held in a loop that attaches to the hyoid bone. The anterior belly is innervated via the mandibular nerve, and the posterior belly is innervated via the facial nerve. It may act to depress the mandible or elevate the hyoid bone.

The mandibular foramen is an opening on the internal surface of the ramus of the mandible. It allows for divisions of the mandibular nerve and blood vessels to pass through.

Chin augmentation using surgical implants alter the underlying structure of the face, intended to balance the facial features. The specific medical terms mentoplasty and genioplasty are used to refer to the reduction and addition of material to a patient's chin. This can take the form of chin height reduction or chin rounding by osteotomy, or chin augmentation using implants. Altering the facial balance is commonly performed by modifying the chin using an implant inserted through the mouth. The intent is to provide a suitable projection of the chin as well as the correct height of the chin which is in balance with the other facial features.

Orthognathic surgery, also known as corrective jaw surgery or simply jaw surgery, is surgery designed to correct conditions of the jaw and lower face related to structure, growth, airway issues including sleep apnea, TMJ disorders, malocclusion problems primarily arising from skeletal disharmonies, and other orthodontic dental bite problems that cannot be treated easily with braces, as well as the broad range of facial imbalances, disharmonies, asymmetries, and malproportions where correction may be considered to improve facial aesthetics and self-esteem.

The pharyngeal arches, also known as visceral arches, are structures seen in the embryonic development of vertebrates that are recognisable precursors for many structures. In fish, the arches are known as the branchial arches, or gill arches.

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis or line of junction where the two lateral halves of the mandible typically fuse in the first year of life. It is not a true symphysis as there is no cartilage between the two sides of the mandible.

Pierre Robin sequence is a congenital defect observed in humans which is characterized by facial abnormalities. The three main features are micrognathia, which causes glossoptosis, which in turn causes breathing problems due to obstruction of the upper airway. A wide, U-shaped cleft palate is commonly also present. PRS is not merely a syndrome, but rather it is a sequence—a series of specific developmental malformations which can be attributed to a single cause.

Mammalodontidae is a family of extinct whales known from the Oligocene of Australia and New Zealand.

Occlusion, in a dental context, means simply the contact between teeth. More technically, it is the relationship between the maxillary (upper) and mandibular (lower) teeth when they approach each other, as occurs during chewing or at rest.

Durophagy is the eating behavior of animals that consume hard-shelled or exoskeleton-bearing organisms, such as corals, shelled mollusks, or crabs. It is mostly used to describe fish, but is also used when describing reptiles, including fossil turtles, placodonts and invertebrates, as well as "bone-crushing" mammalian carnivores such as hyenas. Durophagy requires special adaptions, such as blunt, strong teeth and a heavy jaw. Bite force is necessary to overcome the physical constraints of consuming more durable prey and gain a competitive advantage over other organisms by gaining access to more diverse or exclusive food resources earlier in life. Those with greater bite forces require less time to consume certain prey items as a greater bite force can increase the net rate of energy intake when foraging and enhance fitness in durophagous species.

Cephalometric analysis is the clinical application of cephalometry. It is analysis of the dental and skeletal relationships of a human skull. It is frequently used by dentists, orthodontists, and oral and maxillofacial surgeons as a treatment planning tool. Two of the more popular methods of analysis used in orthodontology are the Steiner analysis and the Downs analysis. There are other methods as well which are listed below.

Mandibular fracture, also known as fracture of the jaw, is a break through the mandibular bone. In about 60% of cases the break occurs in two places. It may result in a decreased ability to fully open the mouth. Often the teeth will not feel properly aligned or there may be bleeding of the gums. Mandibular fractures occur most commonly among males in their 30s.

The simian shelf is a bony thickening on the front of the ape mandible. Its function is to reinforce the jaw, though it also has the effect of considerably reducing the movement of the tongue by restricting the area available for muscles.

A jaw abnormality is a disorder in the formation, shape and/or size of the jaw. In general abnormalities arise within the jaw when there is a disturbance or fault in the fusion of the mandibular processes. The mandible in particular has the most differential typical growth anomalies than any other bone in the human skeleton. This is due to variants in the complex symmetrical growth pattern which formulates the mandible.

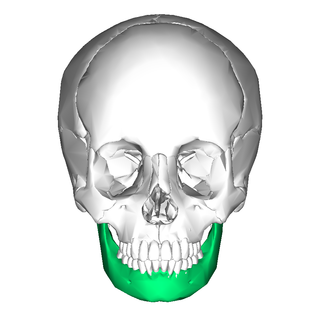

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible, lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lower – and typically more mobile – component of the mouth.

Most bony fishes have two sets of jaws made mainly of bone. The primary oral jaws open and close the mouth, and a second set of pharyngeal jaws are positioned at the back of the throat. The oral jaws are used to capture and manipulate prey by biting and crushing. The pharyngeal jaws, so-called because they are positioned within the pharynx, are used to further process the food and move it from the mouth to the stomach.

Erik Arne Björk was a Swedish dentist famous for his The Face in Profile Analysis which he published in 1947. He is also known to develop the implant radiography.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)