Contents

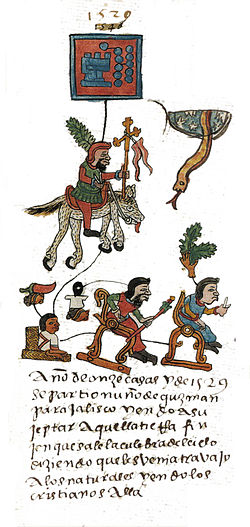

The Codex Telleriano-Remensis is divided into three sections. The first section, spanning the first seven pages, describes the 365-day solar calendar, called the xiuhpohualli . The second section, spanning pages 8 to 24, is a tonalamatl , describing the 260-day tonalpohualli calendar. The third section is a history, itself divided into two sections which differ stylistically. Pages 25 to 28 are an account of migrations during the 12th and 13th centuries, while the remaining pages of the codex record historical events, such as the ascensions and deaths of rulers, battles, earthquakes, and eclipses, from the 14th century to the 16th century, including events of early Colonial Mexico.

The codex contains twelve references to a series of earthquakes that occurred between 1460 and 1542. [2] This was found by Gerardo Suárez and Virginia García-Acosta to be the earliest references to seismic activity in the Americas. [2] Suárez commented that the find was not surprising since earthquakes were both frequent in the area and important to Mesoamerican cosmology. [2]

Publication

In 1995, a facsimile reproduction of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis made from films was published by the University of Texas Press, with commentary by Eloise Quiñones Keber. During the process of photographing and re-binding the manuscript for this publication, two pages were accidentally swapped, and appear as such in the facsimile: page 13, with Tecziztecatl on the recto and Nahui Ehecatl on the verso; and page 19, with Tamoanchan on the recto and Xolotl on the verso. [3]

The codex is also available as an electronic document from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. [4]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.