Related Research Articles

Aztec mythology is the body or collection of myths of the Aztec civilization of Central Mexico. The Aztecs were Nahuatl-speaking groups living in central Mexico and much of their mythology is similar to that of other Mesoamerican cultures. According to legend, the various groups who became the Aztecs arrived from the North into the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco. The location of this valley and lake of destination is clear – it is the heart of modern Mexico City – but little can be known with certainty about the origin of the Aztec. There are different accounts of their origin. In the myth, the ancestors of the Mexica/Aztec came from a place in the north called Aztlan, the last of seven nahuatlacas to make the journey southward, hence their name "Azteca." Other accounts cite their origin in Chicomoztoc, "the place of the seven caves", or at Tamoanchan.

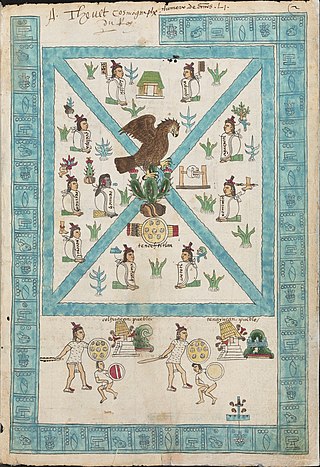

The Aztecs were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec Empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427: Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Mexica or Tenochca, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era, as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821). The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early 19th century.

Mayahuel is the female deity associated with the maguey plant among cultures of central Mexico in the Postclassic era of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican chronology, and in particular of the Aztec cultures. As the personification of the maguey plant, Mayahuel is also part of a complex of interrelated maternal and fertility goddesses in Aztec religion and is also connected with notions of fecundity and nourishment.

In Aztec mythology, Xolotl was a god of fire and lightning. He was commonly depicted as a dog-headed man and was a soul-guide for the dead. He was also god of twins, monsters, death, misfortune, sickness, and deformities. Xolotl is the canine brother and twin of Quetzalcoatl, the pair being sons of the virgin Chimalma. He is the dark personification of Venus, the evening star, and was associated with heavenly fire. The axolotl is named after him.

Huitzilopochtli is the solar and war deity of sacrifice in Aztec religion. He was also the patron god of the Aztecs and their capital city, Tenochtitlan. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire.

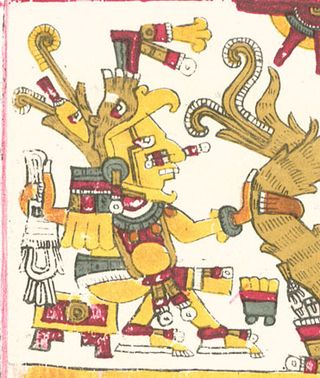

In Aztec mythology, Centeōtl is the maize deity. Cintli means "dried maize still on the cob" and teōtl means "deity". According to the Florentine Codex, Centeotl is the son of the earth goddess, Tlazolteotl and solar deity Piltzintecuhtli, the planet Mercury. He was born on the day-sign 1 Xochitl. Another myth claims him as the son of the goddess Xochiquetzal. The majority of evidence gathered on Centeotl suggests that he is usually portrayed as a young man, with yellow body colouration. Some specialists believe that Centeotl used to be the maize goddess Chicomecōātl. Centeotl was considered one of the most important deities of the Aztec era. There are many common features that are shown in depictions of Centeotl. For example, there often seems to be maize in his headdress. Another striking trait is the black line passing down his eyebrow, through his cheek and finishing at the bottom of his jaw line. These face markings are similarly and frequently used in the late post-classic depictions of the 'foliated' Maya maize god.

Tlālōcān is described in several Aztec codices as a paradise, ruled over by the rain deity Tlāloc and his consort Chalchiuhtlicue. It absorbed those who died through drowning or lightning, or as a consequence of diseases associated with the rain deity. Tlālōcān has also been recognized in certain wall paintings of the much earlier Teotihuacan culture. Among modern Nahua-speaking peoples of the Gulf Coast, Tlālōcān survives as an all-encompassing concept embracing the subterranean world and its denizens.

In Aztec mythology, Tōnacācihuātl was a creator and goddess of fertility, worshiped for peopling the earth and making it fruitful. Most Colonial-era manuscripts equate her with Ōmecihuātl. Tōnacācihuātl was the consort of Tōnacātēcuhtli. She is also referred to as Ilhuicacihuātl or "Heavenly Lady."

The Aztec or Mexica calendar is the calendrical system used by the Aztecs as well as other Pre-Columbian peoples of central Mexico. It is one of the Mesoamerican calendars, sharing the basic structure of calendars from throughout the region.

Ītzpāpalōtl was a goddess in Aztec religion.

Tamōhuānchān is a mythical location of origin known to the Mesoamerican cultures of the central Mexican region in the Late Postclassic period. In the mythological traditions and creation accounts of Late Postclassic peoples such as the Aztec, Tamoanchan was conceived as a paradise where the gods created the first of the present human race out of sacrificed blood and ground human bones which had been stolen from the Underworld of Mictlan.

Itzcoatl was the fourth king of Tenochtitlan, and the founder of the Aztec Empire, ruling from 1427 to 1440. Under Itzcoatl the Mexica of Tenochtitlan threw off the domination of the Tepanecs and established the Triple Alliance together with the other city-states Tetzcoco and Tlacopan.

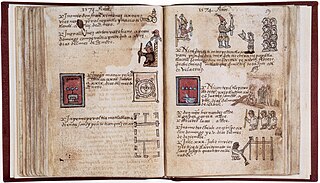

Aztec codices are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.

The Aubin Codex is an 81-leaf Aztec codex written in alphabetic Nahuatl on paper from Europe. Its textual and pictorial contents represent the history of the Aztec peoples who fled Aztlán, lived during the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, and into the early Spanish colonial period, ending in 1608. It is now in the British Museum in London.

Teōtl is a Nahuatl term for sacredness or divinity that is sometimes translated as "god". For the Aztecs teotl was the metaphysical omnipresence upon which their religious philosophy was based.

Azcaxochitl, or Azcasuch was a cihuatlatoani (queen) of the pre-Columbian Acolhua altepetl of Tepetlaoztoc in the Valley of Mexico. Her name is Nahuatl for a kind of a flower.

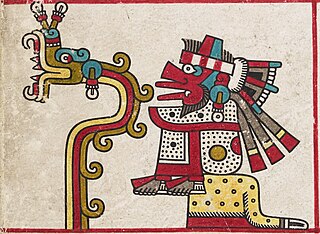

Quetzalcoatl is a deity in Aztec culture and literature. Among the Aztecs, he was related to wind, Venus, Sun, merchants, arts, crafts, knowledge, and learning. He was also the patron god of the Aztec priesthood. He was one of several important gods in the Aztec pantheon, along with the gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli. The two other gods represented by the planet Venus are Tlaloc and Xolotl.

Nahuatl, Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about 1.7 million Nahuas, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller populations in the United States.

Cipactonal is the Aztec god of astrology and calendars. Oxomoco and Cipactonal were said to be the first human couple, and the Aztec comparison to Adam and Eve in regard to human creation and evolution. They bore a son named Piltzin-tecuhtli, who married a maiden, daughter of Xochiquetzal.

References

- ↑ Otilia Meza (1981). Editorial Universo México (ed.). El Mundo Mágico de los Dioses del Anáhuac (in Spanish). México. p. 47. ISBN 968-35-0093-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Austin, Alfredo López (1988). The human body and ideology: concepts of the ancient Nahuas. University of Utah Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-87480-260-3 . Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Austin, Alfredo López (1996). The rabbit on the face of the moon: mythology in the mesoamerican tradition. University of Utah Press. pp. 102–6. ISBN 978-0-87480-527-7 . Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ "Aztec cosmology". University of Texas. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ New World Archaeological Foundation (1995). Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation. New World Archaeological Foundation. p. 227. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- 1 2 Squier, Ephraim George; Comparato, Frank E. (1990). Observations on the archaeology and ethnology of Nicaragua. Labyrinthos. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-911437-08-9 . Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- 1 2 Boone, Elizabeth Hill (2007). Cycles of time and meaning in the Mexican books of fate. University of Texas Press. pp. 24, 25–. ISBN 978-0-292-71263-8 . Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- 1 2 Smith, Mary Elizabeth; Boone, Elizabeth Hill (2005). Painted books and indigenous knowledge in Mesoamerica: manuscript studies in honor of Mary Elizabeth Smith. Middle American Research Institute. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-939238-99-6 . Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ Nowotny, Karl Anton; Everett, George A.; Sisson, Edward B. (2005). Tlacuilolli: style and contents of the Mexican pictorial manuscripts with a catalog of the Borgia Group. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8061-3653-0 . Retrieved 26 October 2011.