Related Research Articles

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., kaolin, Al2Si2O5(OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especially quartz and calcite. Shale is characterized by its tendency to split into thin layers (laminae) less than one centimeter in thickness. This property is called fissility. Shale is the most common sedimentary rock.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Diagenesis is the process that describes physical and chemical changes in sediments first caused by water-rock interactions, microbial activity, and compaction after their deposition. Increased pressure and temperature only start to play a role as sediments become buried much deeper in the Earth's crust. In the early stages, the transformation of poorly consolidated sediments into sedimentary rock (lithification) is simply accompanied by a reduction in porosity and water expulsion, while their main mineralogical assemblages remain unaltered. As the rock is carried deeper by further deposition above, its organic content is progressively transformed into kerogens and bitumens.

Sedimentary basins are region-scale depressions of the Earth's crust where subsidence has occurred and a thick sequence of sediments have accumulated to form a large three-dimensional body of sedimentary rock. They form when long-term subsidence creates a regional depression that provides accommodation space for accumulation of sediments. Over millions or tens or hundreds of millions of years the deposition of sediment, primarily gravity-driven transportation of water-borne eroded material, acts to fill the depression. As the sediments are buried, they are subject to increasing pressure and begin the processes of compaction and lithification that transform them into sedimentary rock.

Sedimentology encompasses the study of modern sediments such as sand, silt, and clay, and the processes that result in their formation, transport, deposition and diagenesis. Sedimentologists apply their understanding of modern processes to interpret geologic history through observations of sedimentary rocks and sedimentary structures.

Back-stripping is a geophysical analysis technique used on sedimentary rock sequences. It is used to quantitatively estimate the depth that the basement would be in the absence of sediment and water loading. This depth provides a measure of the unknown tectonic driving forces that are responsible for basin formation. By comparing backstripped curves to theoretical curves for basin subsidence and uplift it is possible to deduce information on the basin forming mechanisms.

The Perth Basin is a thick, elongated sedimentary basin in Western Australia. It lies beneath the Swan Coastal Plain west of the Darling Scarp, representing the western limit of the much older Yilgarn Craton, and extends further west offshore. Cities and towns including Perth, Busselton, Bunbury, Mandurah and Geraldton are built over the Perth Basin.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic to refer to sedimentary rocks and particles in sediment transport, whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

A foreland basin is a structural basin that develops adjacent and parallel to a mountain belt. Foreland basins form because the immense mass created by crustal thickening associated with the evolution of a mountain belt causes the lithosphere to bend, by a process known as lithospheric flexure. The width and depth of the foreland basin is determined by the flexural rigidity of the underlying lithosphere, and the characteristics of the mountain belt. The foreland basin receives sediment that is eroded off the adjacent mountain belt, filling with thick sedimentary successions that thin away from the mountain belt. Foreland basins represent an endmember basin type, the other being rift basins. Space for sediments is provided by loading and downflexure to form foreland basins, in contrast to rift basins, where accommodation space is generated by lithospheric extension.

Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%. Strictly speaking, some tests measure the "accessible void", the total amount of void space accessible from the surface.

Tectonic subsidence is the sinking of the Earth's crust on a large scale, relative to crustal-scale features or the geoid. The movement of crustal plates and accommodation spaces produced by faulting brought about subsidence on a large scale in a variety of environments, including passive margins, aulacogens, fore-arc basins, foreland basins, intercontinental basins and pull-apart basins. Three mechanisms are common in the tectonic environments in which subsidence occurs: extension, cooling and loading.

Growth faults are syndepositional or syn-sedimentary extensional faults that initiate and evolve at the margins of continental plates. They extend parallel to passive margins that have high sediment supply. Their fault plane dips mostly toward the basin and has long-term continuous displacement. Figure one shows a growth fault with a concave upward fault plane that has high updip angle and flattened at its base into zone of detachment or décollement. This angle is continuously changing from nearly vertical in the updip area to nearly horizontal in the downdip area.

The Persian Gulf Basin is found between the Eurasian and the Arabian Plate. The Persian Gulf is described as a shallow marginal sea of the Indian Ocean that is located between the south western side of Zagros Mountains and the Arabian Peninsula and south and southeastern side of Oman and the United Arab Emirates. Other countries that border the Persian Gulf basin include; Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain and Iraq. The Persian Gulf extends a distance of 1,000 km (620 mi) with an area of 240,000 km2 (93,000 sq mi). The Arabian Plate basin a wedge-shaped foreland basin which lies beneath the western Zagros thrust and was created as a result of the collision between the Arabian and Eurasian plates.

The North German Basin is a passive-active rift basin located in central and west Europe, lying within the southeasternmost portions of the North Sea and the southwestern Baltic Sea and across terrestrial portions of northern Germany, Netherlands, and Poland. The North German Basin is a sub-basin of the Southern Permian Basin, that accounts for a composite of intra-continental basins composed of Permian to Cenozoic sediments, which have accumulated to thicknesses around 10–12 kilometres (6–7.5 mi). The complex evolution of the basin takes place from the Permian to the Cenozoic, and is largely influenced by multiple stages of rifting, subsidence, and salt tectonic events. The North German Basin also accounts for a significant amount of Western Europe's natural gas resources, including one of the world's largest natural gas reservoir, the Groningen gas field.

The Halibut Field is an oil field, within the Gippsland Basin offshore of the Australian state of Victoria. The oil field is located approximately 64 km offshore of southeastern Australia. The total area of this field is 26.9 km2 and is composed of 10 mappable units.

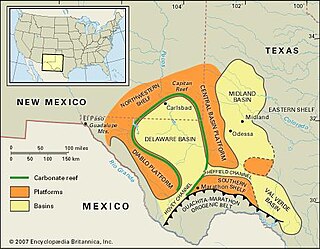

The Val Verde Basin is a marginal foreland basin located in West Texas, just southeast of the Midland Basin. The Val Verde is a sub-basin of the larger Permian Basin and is roughly 24–40 km wide by 240 km long. It is an unconventional system and its sediments were deposited during a long period of flooding during the Middle to Late Cretaceous. This flooding event is referred to as the Western Interior Seaway, and many basins in the Western United States can attribute their oil and gas producing basins to carbonate deposition during this time period.

The Cook Inlet Basin is a northeast-trending collisional forearc basin that stretches from the Gulf of Alaska into South central Alaska, just east of the Matanuska Valley. It is located in the arc-trench gap between the Alaska-Aleutian Range batholith and contains roughly 80,000 cubic miles of sedimentary rocks. These sediments are mainly derived from Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous sediments.

The Nam Con Son Basin formed as a rift basin during the Oligocene period. This basin is the southernmost sedimentary basin offshore of Vietnam, located within coordinates of 6°6'-9°45'N and 106°0-109°30'E in the East Vietnam Sea. It is the largest oil and gas bearing basin in Vietnam and has a number of producing fields.

Hebron Oil Field, located off the coast of Newfoundland, is the fourth field to come on to production in the Jeanne d'Arc Basin. Discovered in 1981 and put online in 2017, the Hebron field is estimated to contain over 700 million barrels of producible hydrocarbons. The field is contained within a fault-bounded Mesozoic rift basin called the Jeanne d'Arc Basin.

The Officer Basin is an intracratonic sedimentary basin that covers roughly 320,000 km2 along the border between southern and western Australia. Exploration for hydrocarbons in this basin has been sparse, but the geology has been examined for its potential as a hydrocarbon reservoir. This basin's extensive depositional history, with sedimentary thicknesses exceeding 6 km and spanning roughly 350 Ma during the Neoproterozoic, make it an ideal candidate for hydrocarbon production.

References

- ↑ Sclater, J.G. & Christie, P.A.F. 1980. Continental stretching: an explanation of the post-mid-Cretaceous subsidence of the Central North Sea Basin. Journal of Geophysical Research, 85, 3711–3739.

- ↑ Lee, E.Y., Novotny, J., Wagreich, M. (2020) Compaction trend estimation and applications to sedimentary basin reconstruction (BasinVis 2.0). Applied Computing and Geosciences, 5, 100015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acags.2019.100015

- ↑ A. C. Fowler and X. S. Yang, Fast and slow compaction in sedimentary basins, SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 59, 365-385 (1998.)

- ↑ D. B. Bahr, E. W. Hutton, J. P. Syvitski, L. F. Pratson, Exponential approximations to compacted sediment porosity profiles, Computers & Geosciences, 27, 691-700 (2001).

- ↑ http://energy.cr.usgs.gov/WEcont/regions/reg3/P3/tps/AU/au314412.pdf%7C%5B%5D USGS report on the Songliao Basin