Tapiola is a district of the municipality of Espoo on the south coast of Finland, and is one of the major urban centres of Espoo. It is located in the western part of Helsinki capital region. The name Tapiola is derived from Tapio, who is the forest god of Finnish mythology, especially as expressed in the Kalevala.

A tower block, high-rise, apartment tower, residential tower, apartment block, block of flats, or office tower is a tall building, as opposed to a low-rise building and is defined differently in terms of height depending on the jurisdiction. It is used as a residential, office building, or other functions including hotel, retail, or with multiple purposes combined. Residential high-rise buildings are also known in some varieties of English, such as British English, as tower blocks and may be referred to as MDUs, standing for multi-dwelling units. A very tall high-rise building is referred to as a skyscraper.

An apartment, flat, or unit is a self-contained housing unit that occupies part of a building, generally on a single story. There are many names for these overall buildings. The housing tenure of apartments also varies considerably, from large-scale public housing, to owner occupancy within what is legally a condominium or leasehold, to tenants renting from a private landlord.

A housing estate is a group of homes and other buildings built together as a single development. The exact form may vary from country to country.

Trellick Tower is a Grade II* listed tower block on the Cheltenham Estate in Kensal Town, London. Opened in 1972, it was commissioned by the Greater London Council and designed in the Brutalist style by architect Ernő Goldfinger. The tower was planned to replace outdated social accommodation, and designed as an improvement on Goldfinger's earlier Balfron Tower in East London. It was the last major project he worked on, and featured various space-saving designs, along with a separate access tower containing a plant room.

Robin Hood Gardens is a residential estate in Poplar, London, designed in the late 1960s by architects Alison and Peter Smithson and completed in 1972. It was built as a council housing estate with homes spread across 'streets in the sky': social housing characterised by broad aerial walkways in long concrete blocks, much like the Park Hill estate in Sheffield; it was informed by, and a reaction against, Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation. The estate was built by the Greater London Council, but subsequently the London Borough of Tower Hamlets became the landlord.

Multifamily residential, also known as multidwelling unit (MDU), is a classification of housing where multiple separate housing units for residential inhabitants are contained within one building or several buildings within one complex. Units can be next to each other, or stacked on top of each other. Common forms include apartment building and condominium, where typically the units are owned individually rather than leased from a single building owner. Many intentional communities incorporate multifamily residences, such as in cohousing projects.

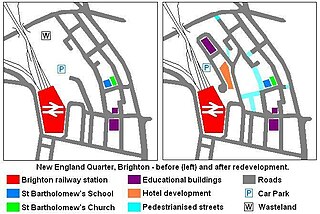

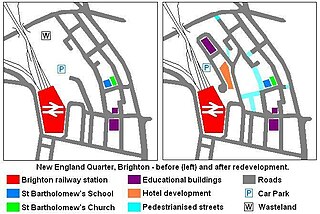

The New England Quarter is a mixed-use development in the city of Brighton and Hove, England. It was built between 2004 and 2008 on the largest brownfield site in the city, adjacent to Brighton railway station. Most parts of the scheme have been finished, but other sections are still being built and one major aspect of the original plan was refused planning permission.

International Plaza is a high-rise commercial and residential building at 10 Anson Road in Tanjong Pagar, within the Downtown Core of Singapore, next to Tanjong Pagar MRT station on the East West line.

The Cranbrook Estate is a housing estate in Bethnal Green, London, England. It is located next to Roman Road and is based around a figure of eight street called Mace Street. The estate was designed by Francis Skinner, Douglas Bailey and an elder mentor, the Soviet émigré Berthold Lubetkin.

The 1950s and 1960s saw the construction of numerous brutalist apartment blocks in Sheffield, England. The Sheffield City Council had been clearing inner-city residential slums since the early 1900s. Prior to the 1950s these slums were replaced with low-rise council housing, mostly constructed in new estates on the edge of the city. By the mid-1950s the establishment of a green belt had led to a shortage of available land on the edges of the city, whilst the government increased subsidies for the construction of high-rise apartment towers on former slum land, so the council began to construct high-rise inner city estates, adopting modernist designs and industrialised construction techniques, culminating in the construction of the award-winning Gleadless Valley and Park Hill estates.

The Southgate Estate was a modernist public housing project located in Runcorn New Town and completed in 1977. The estate was designed by James Stirling, and comprised 1,500 residential units intended to house 6,000 people. The estate was demolished between 1990 and 1992 and replaced with another housing development, known as Hallwood Park, based around more traditional design principles.

George Finch was a British architect. He was a committed socialist who believed architecture had the power to transform the lives of post-war Londoners. Finch's ideals drove his passion for designing social housing, civic and environmental buildings for everyday people built to the highest building standards.

Mordechai Benshemesh was a noted architect who practiced in Melbourne, Australia from the 1950s to the 1970s. Born in Palestine, he was one of a number of often Jewish émigré architects who migrated to Australia both before and after World War II who brought a different approach to architecture, as well as an appreciation of apartment living. He is best known as the architect for one of the city's first high rise modernist apartment blocks, Edgewater Towers in St Kilda.

Public housing in the United Kingdom, also known as council housing or social housing, provided the majority of rented accommodation until 2011, when the number of households in private rental housing surpassed the number in social housing. Dwellings built for public or social housing use are built by or for local authorities and known as council houses. Since the 1980s non-profit housing associations became more important and subsequently the term "social housing" became widely used, as technically council housing only refers to housing owned by a local authority, though the terms are largely used interchangeably.

A council garden estate is a housing estate planned and built for the rehousing of people from decaying inner city areas, pioneered by Ted Hollamby at Cressingham Gardens, Lambeth, in the 1960s. It was a reaction to the philosophy of Ernő Goldfinger, Lubetkin and Le Corbusier who saw a housing estate as an architectural monument. Hollamby sought an anti- monumental architecture, to design for the wishes and needs of the people. High density was achieved by pedestrianising the estate and having external car-parking

Myatt's Fields South is a social housing estate located between Brixton Road and Camberwell New Road in South London. It is on land that once formed part of the Lambeth Wick estate.

The Brandon Estate is a social housing estate in Walworth, London Borough of Southwark, south London. Situated to the south of Kennington Park, it was built in 1958 by the London County Council, to designs by Edward Hollamby and Roger Westman.

Central Hill is a social housing estate in the London Borough of Lambeth. It was designed by Rosemary Stjernstedt, Roger Westman and the Lambeth Council planning department during the directorship of Ted Hollamby. It comprises more than 450 homes built in 1966-74 near the site of the former Crystal Palace. Lambeth Council plans to demolish the estate so that it can build an extra 400 homes, many for private sale, so that it can finance the construction of new social housing.

Roger Ulick Branch Westman was a British architect. He is best known for his designs of council housing in London.