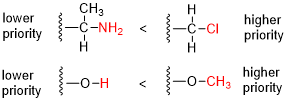

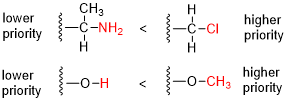

In organic chemistry, the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog (CIP) sequence rules are a standard process to completely and unequivocally name a stereoisomer of a molecule. The purpose of the CIP system is to assign an R or S descriptor to each stereocenter and an E or Z descriptor to each double bond so that the configuration of the entire molecule can be specified uniquely by including the descriptors in its systematic name. A molecule may contain any number of stereocenters and any number of double bonds, and each usually gives rise to two possible isomers. A molecule with an integer n describing the number of stereocenters will usually have 2n stereoisomers, and 2n−1 diastereomers each having an associated pair of enantiomers. The CIP sequence rules contribute to the precise naming of every stereoisomer of every organic molecule with all atoms of ligancy of fewer than 4.

In stereochemistry, stereoisomerism, or spatial isomerism, is a form of isomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. This contrasts with structural isomers, which share the same molecular formula, but the bond connections or their order differs. By definition, molecules that are stereoisomers of each other represent the same structural isomer.

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoisomers, which by definition have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but differ in structural formula. For this reason, it is also known as 3D chemistry—the prefix "stereo-" means "three-dimensionality".

In chemistry, a racemic mixture, or racemate, is one that has equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule or salt. Racemic mixtures are rare in nature, but many compounds are produced industrially as racemates.

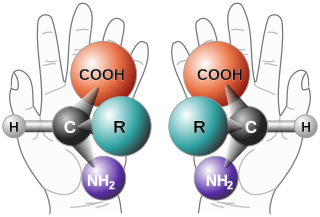

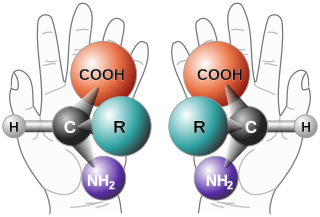

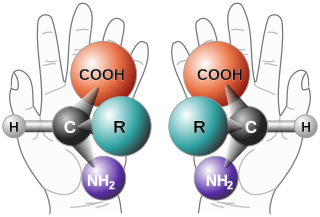

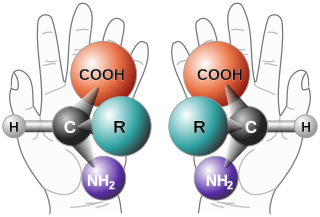

In chemistry, an enantiomer – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical antipode – is one of two stereoisomers that are non-superposable onto their own mirror image. Enantiomers are much like one's right and left hands, when looking at the same face, they cannot be superposed onto each other. No amount of reorientation in three spatial dimensions will allow the four unique groups on the chiral carbon to line up exactly. The number of stereoisomers a molecule has can be determined by the number of chiral carbons it has. Stereoisomers include both enantiomers and diastereomers.

In chemistry, racemization is a conversion, by heat or by chemical reaction, of an optically active compound into a racemic form. This creates a 1:1 molar ratio of enantiomers and is referred too as a racemic mixture. Plus and minus forms are called Dextrorotation and levorotation. The D and L enantiomers are present in equal quantities, the resulting sample is described as a racemic mixture or a racemate. Racemization can proceed through a number of different mechanisms, and it has particular significance in pharmacology as different enantiomers may have different pharmaceutical effects.

In stereochemistry, a stereocenter of a molecule is an atom (center), axis or plane that is the focus of stereoisomerism; that is, when having at least three different groups bound to the stereocenter, interchanging any two different groups creates a new stereoisomer. Stereocenters are also referred to as stereogenic centers.

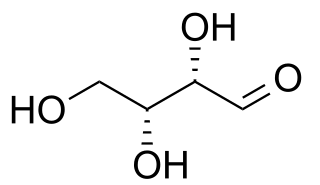

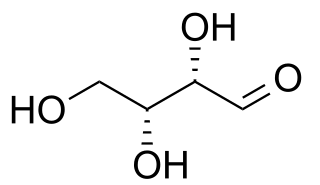

In stereochemistry, diastereomers are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have different configurations at one or more of the equivalent (related) stereocenters and are not mirror images of each other. When two diastereoisomers differ from each other at only one stereocenter, they are epimers. Each stereocenter gives rise to two different configurations and thus typically increases the number of stereoisomers by a factor of two.

In chemistry, a molecule or ion is called chiral if it cannot be superposed on its mirror image by any combination of rotations, translations, and some conformational changes. This geometric property is called chirality. The terms are derived from Ancient Greek χείρ (cheir) 'hand'; which is the canonical example of an object with this property.

Enantioselective synthesis, also called asymmetric synthesis, is a form of chemical synthesis. It is defined by IUPAC as "a chemical reaction in which one or more new elements of chirality are formed in a substrate molecule and which produces the stereoisomeric products in unequal amounts."

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during a non-stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during a non-stereospecific transformation of a pre-existing one. The selectivity arises from differences in steric and electronic effects in the mechanistic pathways leading to the different products. Stereoselectivity can vary in degree but it can never be total since the activation energy difference between the two pathways is finite. Both products are at least possible and merely differ in amount. However, in favorable cases, the minor stereoisomer may not be detectable by the analytic methods used.

In stereochemistry, enantiomeric excess (ee) is a measurement of purity used for chiral substances. It reflects the degree to which a sample contains one enantiomer in greater amounts than the other. A racemic mixture has an ee of 0%, while a single completely pure enantiomer has an ee of 100%. A sample with 70% of one enantiomer and 30% of the other has an ee of 40%.

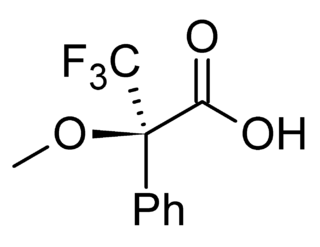

A chiral derivatizing agent (CDA) also known as a chiral resolving reagent, is a chiral auxiliary used to convert a mixture of enantiomers into diastereomers in order to analyze the quantities of each enantiomer present within the mix. Analysis can be conducted by spectroscopy or by chromatography. The use of chiral derivatizing agents has declined with the popularization of chiral HPLC. Besides analysis, chiral derivatization is also used for chiral resolution, the actual physical separation of the enantiomers.

Chiral resolution, or enantiomeric resolution, is a process in stereochemistry for the separation of racemic compounds into their enantiomers. It is an important tool in the production of optically active compounds, including drugs. Another term with the same meaning is optical resolution.

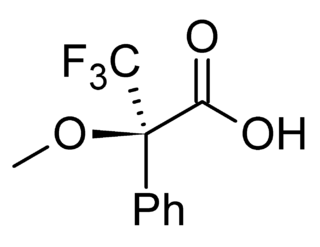

A chiral shift reagent is a reagent used in analytical chemistry for determining the optical purity of a sample. Some analytical techniques such as HPLC and NMR, in their most commons forms, cannot distinguish enantiomers within a sample, but can distinguish diastereomers. Therefore, converting a mixture of enantiomers to a corresponding mixture of diastereomers can allow analysis.

Pirkle's alcohol is an off-white, crystalline solid that is stable at room temperature when protected from light and oxygen. This chiral molecule is typically used, in nonracemic form, as a chiral shift reagent in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, in order to simultaneously determine absolute configuration and enantiomeric purity of other chiral molecules. The molecule is named after William H. Pirkle, Professor of Chemistry at the University of Illinois whose group reported its synthesis and its application as a chiral shift reagent.

Chiral Lewis acids (CLAs) are a type of Lewis acid catalyst. These acids affect the chirality of the substrate as they react with it. In such reactions, synthesis favors the formation of a specific enantiomer or diastereomer. The method is an enantioselective asymmetric synthesis reaction. Since they affect chirality, they produce optically active products from optically inactive or mixed starting materials. This type of preferential formation of one enantiomer or diastereomer over the other is formally known as asymmetric induction. In this kind of Lewis acid, the electron-accepting atom is typically a metal, such as indium, zinc, lithium, aluminium, titanium, or boron. The chiral-altering ligands employed for synthesizing these acids often have multiple Lewis basic sites that allow the formation of a ring structure involving the metal atom.

In chemistry, isomers are molecules or polyatomic ions with identical molecular formulae – that is, same number of atoms of each element – but distinct arrangements of atoms in space. Isomerism is existence or possibility of isomers.

An enantiopure drug is a pharmaceutical that is available in one specific enantiomeric form. Most biological molecules are present in only one of many chiral forms, so different enantiomers of a chiral drug molecule bind differently to target receptors. Chirality can be observed when the geometric properties of an object is not superimposable with its mirror image. Two forms of a molecule are formed from a chiral carbon, these two forms are called enantiomers. One enantiomer of a drug may have a desired beneficial effect while the other may cause serious and undesired side effects, or sometimes even beneficial but entirely different effects. The desired enantiomer is known as an eutomer while the undesired enantiomer is known as the distomer. When equal amounts of both enantiomers are found in a mixture, the mixture is known as a racemic mixture. If a mixture for a drug does not have a 1:1 ratio of its enantiomers it is a candidate for an enantiopure drug. Advances in industrial chemical processes have made it economical for pharmaceutical manufacturers to take drugs that were originally marketed as a racemic mixture and market the individual enantiomers, either by specifically manufacturing the desired enantiomer or by resolving a racemic mixture. On a case-by-case basis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has allowed single enantiomers of certain drugs to be marketed under a different name than the racemic mixture. Also case-by-case, the United States Patent Office has granted patents for single enantiomers of certain drugs. The regulatory review for marketing approval and for patenting is independent, and differs country by country.

Chiral analysis refers to the quantification of component enantiomers of racemic drug substances or pharmaceutical compounds. Other synonyms commonly used include enantiomer analysis, enantiomeric analysis, and enantioselective analysis. Chiral analysis includes all analytical procedures focused on the characterization of the properties of chiral drugs. Chiral analysis is usually performed with chiral separation methods where the enantiomers are separated on an analytical scale and simultaneously assayed for each enantiomer.