Electricity generation is the process of generating electric power from sources of primary energy. For utilities in the electric power industry, it is the stage prior to its delivery to end users or its storage.

India is the third largest producer of electricity in the world. During the fiscal year (FY) 2022–23, the total electricity generation in the country was 1,844 TWh, of which 1,618 TWh was generated by utilities.

In 2022, 79.6% of Taiwan's electricity generation came from fossil fuels, 9.1% from nuclear, 8.6% from renewables, and 1.2% from hydro. Taiwan relies on imports for almost 98% of its energy, which leaves the island's energy supply vulnerable to external disruption. In order to reduce this dependence, the Ministry of Economic Affairs' Bureau of Energy has been actively promoting energy research at several universities since the 1990s.

Energy in the United Kingdom came mostly from fossil fuels in 2021. Total energy consumption in the United Kingdom was 142.0 million tonnes of oil equivalent in 2019. In 2014, the UK had an energy consumption per capita of 2.78 tonnes of oil equivalent compared to a world average of 1.92 tonnes of oil equivalent. Demand for electricity in 2014 was 34.42 GW on average coming from a total electricity generation of 335.0 TWh.

Energy in Bulgaria is among the most important sectors of the national economy and encompasses energy and electricity production, consumption and transportation in Bulgaria. The national energy policy is implemented by the National Assembly and the Government of Bulgaria, conducted by the Ministry of Energy and regulated by the Energy and Water Regulatory Commission. The completely state-owned company Bulgarian Energy Holding owns subsidiaries operating in different energy sectors, including electricity: Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant, Maritsa Iztok 2 Thermal Power Plant, NEK EAD and Elektroenergien sistemen operator (ESO); natural gas: Bulgargaz and Bulgartransgaz; coal mining: Maritsa Iztok Mines. In Bulgaria, energy prices for households are state-controlled, while commercial electricity prices are determined by the market.

The energy policy of India is to increase the locally produced energy in India and reduce energy poverty, with more focus on developing alternative sources of energy, particularly nuclear, solar and wind energy. Net energy import dependency was 40.9% in 2021-22.

China is both the world's largest energy consumer and the largest industrial country, and ensuring adequate energy supply to sustain economic growth has been a core concern of the Chinese Government since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. Since the country's industrialization in the 1960s, China is currently the world's largest emitter of greenhouse gases, and coal in China is a major cause of global warming. However, from 2010 to 2015 China reduced energy consumption per unit of GDP by 18%, and CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 20%. On a per-capita basis, China was only the world's 51st largest emitter of greenhouse gases in 2016. China is also the world's largest renewable energy producer, and the largest producer of hydroelectricity, solar power and wind power in the world. The energy policy of China is connected to its industrial policy, where the goals of China's industrial production dictate its energy demand managements.

Energy in Finland describes energy and electricity production, consumption and import in Finland. Energy policy of Finland describes the politics of Finland related to energy. Electricity sector in Finland is the main article regarding electricity in Finland.

Energy in Belgium describes energy and electricity production, consumption and import in Belgium.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo was a net energy exporter in 2008. Most energy was consumed domestically in 2008. According to the IEA statistics the energy export was in 2008 small and less than from the Republic of Congo. 2010 population figures were 3.8 million for the RC compared to CDR 67.8 Million.

The utility electricity sector in Bangladesh has one national grid with an installed capacity of 25,700 MW as of June 2022. Bangladesh's energy sector is not up to the mark. However, per capita energy consumption in Bangladesh is considered higher than the production. Electricity was introduced to the country on 7 December 1901 under British rule.

Energy in Austria describes energy and electricity production, consumption and import in Austria. Austria is very reliant on hydro as an energy source, supported by imported oil and natural gas supplies. It is planned by 2030 to become 100% electricity supplied by renewable sources, primarily hydro, wind and solar.

Energy in Greece is dominated by fossil gas and oil. Electricity generation is dominated by the one third state owned Public Power Corporation. In 2009 DEI supplied for 85.6% of all electric energy demand in Greece, while the number fell to 77.3% in 2010. Almost half (48%) of DEI's power output in 2010 was generated using lignite. 12% of Greece's electricity comes from hydroelectric power plants and another 20% from natural gas. Between 2009 and 2010, independent companies' energy production increased by 56%, from 2,709 Gigawatt hour in 2009 to 4,232 GWh in 2010.

Energy in Portugal describes energy and electricity production, consumption and import in Portugal. Energy policy of Portugal will describe the politics of Portugal related to energy more in detail. Electricity sector in Portugal is the main article of electricity in Portugal.

Primary energy use in Slovakia was 194 TWh and 36 TWh per million inhabitants in 2009.

An energy transition is a significant structural change in an energy system regarding supply and consumption. Currently, a transition to sustainable energy is underway to limit climate change. It is also called renewable energy transition. The current transition is driven by a recognition that global greenhouse-gas emissions must be drastically reduced. This process involves phasing-down fossil fuels and re-developing whole systems to operate on low carbon electricity. A previous energy transition took place during the industrial revolution and involved an energy transition from wood and other biomass to coal, followed by oil and most recently natural gas.

Most energy in Israel comes from fossil fuels. The country's total primary energy demand is significantly higher than its total primary energy production, relying heavily on imports to meet its energy needs. Total primary energy consumption was 304 TWh (1.037 quad) in 2016, or 26.2 million tonne of oil equivalent.

Nepal is a country enclosed by land, situated between China and India. It has a total area of 147,181 square kilometers and a population of 29.16 million. It has a small economy, with a GDP of $33.66 billion in 2020, amounting to about 1% of South Asia and 0.04% of the World's GDP.

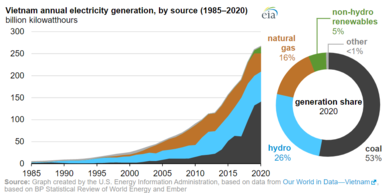

Vietnam utilizes four main sources of renewable energy: hydroelectricity, wind power, solar power and biomass. At the end of 2018, hydropower was the largest source of renewable energy, contributing about 40% to the total national electricity capacity. In 2020, wind and solar had a combined share of 10% of the country's electrical generation, already meeting the government's 2030 goal, suggesting future displacement of growth of coal capacity. By the end of 2020, the total installed capacity of solar and wind power had reached over 17 GW. Over 25% of total power capacity is from variable renewable energy sources. The commercial biomass electricity generation is currently slow and limited to valorizing bagasse only, but the stream of forest products, agricultural and municipal waste is increasing. The government is studying a renewable portfolio standard that could promote this energy source.