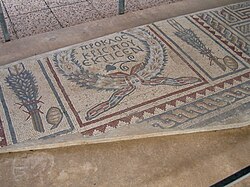

Sukkot is a Torah-commanded holiday celebrated for seven days, beginning on the 15th day of the month of Tishrei. It is one of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals on which Israelites were commanded to make a pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. Originally a harvest festival celebrating the autumn harvest, Sukkot’s modern observance is characterized by festive meals in a sukkah, a temporary wood-covered hut, celebrating the Exodus from Egypt.

Shemini Atzeret is a Jewish holiday. It is celebrated on the 22nd day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei in the Land of Israel, and on the 22nd and 23rd outside the Land, usually coinciding with late September or early October. It directly follows the Jewish festival of Sukkot which is celebrated for seven days, and thus Shemini Atzeret is literally the eighth day. It is a separate—yet connected—holy day devoted to the spiritual aspects of the festival of Sukkot. Part of its duality as a holy day is that it is simultaneously considered to be both connected to Sukkot and also a separate festival in its own right.

Lulav is a closed frond of the date palm tree. It is one of the Four Species used during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. The other Species are the hadass (myrtle), aravah (willow), and etrog (citron). When bound together, the lulav, hadass, and aravah are commonly referred to as "the lulav".

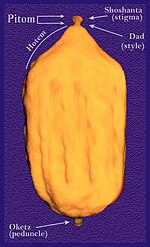

The citron, historically cedrate, is a large fragrant citrus fruit with a thick rind. It is said to resemble a 'huge, rough lemon'. It is one of the original citrus fruits from which all other citrus types developed through natural hybrid speciation or artificial hybridization. Though citron cultivars take on a wide variety of physical forms, they are all closely related genetically. It is used in Asian and Mediterranean cuisine, traditional medicines, perfume, and religious rituals and offerings. Hybrids of citrons with other citrus are commercially more prominent, notably lemons and many limes.

Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, also known as the Chazon Ish after his magnum opus, was a Belarusian-born Orthodox rabbi who later became one of the leaders of Haredi Judaism in Israel, where he spent his final 20 years, from 1933 to 1953.

The four species are four plants—the etrog, lulav, hadass, and aravah—mentioned in the Torah as being relevant to the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. Observant Jews tie together three types of branches and one type of fruit and wave them in a special ceremony each day of the Sukkot holiday, excluding Shabbat. According to Rabbinic Judaism, the waving of the four plants is a mitzvah prescribed by the Torah, and it contains symbolic allusions to a Jew's service of God.

Hadass is a branch of the myrtle tree that forms part of the lulav used on the Jewish holiday of Sukkot.

Aravah is a leafy branch of the willow tree. It is one of the Four Species used in a special waving ceremony during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. The other species are the lulav, hadass (myrtle), and etrog (citron).

Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis, or the fingered citron, is an unusually-shaped citron variety whose fruit is segmented into finger-like sections, resembling those seen on representations of the Buddha. It is called Buddha's hand in many languages including English, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, and French.

Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz was an Israeli Haredi Torah leader and rosh yeshiva in Bnei Brak for over 70 years. He was a maggid shiur at Yeshivas Tiferes Tzion from 1940 to 2011 and rosh yeshiva of Yeshivas Ponovezh L’Tzeirim from 1954 to 2009, raising thousands of students. He was a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Degel HaTorah, a member of Mifal HaShas, and nasi (president) of the Acheinu kiruv organization, and played a leading role in the fight for Torah-true education in yeshivas and Talmud Torahs in Israel. In addition to his own Torah works, he published the teachings of his rebbi, Rabbi Shlomo Heiman, in the two-volume Chiddushei Shlomo.

Sukkah is a tractate of the Mishnah and Talmud. Its laws are discussed as well in the Tosefta and both the Babylonian Talmud and Jerusalem Talmud. In most editions it is the sixth volume of twelve in the Order of Moed. Sukkah deals primarily with laws relating to the Jewish holiday of Sukkot. It has five chapters.

The Greek citron variety of Citrus medica was botanically classified by Adolf Engler as the "variety etrog". This refers to its major use for the Jewish ritual etrog during Sukkot.

The Diamante citron is a variety of citron named after the town of Diamante, located in the province of Cosenza, Calabria, on the south-western coast of Italy, which is its most known cultivation point. This is why this variety is sometimes called the "Calabria Esrog". "Esrog" is the Ashkenazi Hebrew name for citron.

The balady citron is a variety of citron, or etrog, grown in Israel and Palestine, mostly for Jewish ritual purposes. Not native to the region, it was imported around 500 or 300 BCE by either Jewish or Greek settlers. Initially not widely grown, it was promoted and popularized in the 1870s by Rabbi Chaim Elozor Wax.

Succade is the candied peel of any of the citrus species, especially from the citron or Citrus medica which is distinct with its extra-thick peel; in addition, the taste of the inner rind of the citron is less bitter than those of the other citrus. However, the term is also occasionally applied to the peel, root, or even entire fruit or vegetable like parsley, fennel and cucurbita which have a bitter taste and are boiled with sugar to get a special "sweet and sour" outcome.

Etrog or Esrog is the Hebrew word for the citron fruit or Citrus medica.

The Yemenite citron is a variety of citron, usually containing no juice vesicles in its fruit's segments. The bearing tree and the mature fruit's size are somewhat larger than the trees and fruit of other varieties of citron.

Eliezer E. Goldschmidt is an emeritus professor of agriculture at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He earned his Ph.D. in 1968 and has been a professor since 1982.

The Moroccan citron is a true citron variety native to Assads, Morocco, which is still today its main center of cultivation.

The history of the Jews in Calabria reaches back over two millennia. Calabria is at the very south of the Italian peninsula, to which it is connected by the Monte Pollino massif, while on the east, south and west it is surrounded by the Ionian and Tyrrhenian seas. Jews have had a presence in Calabria for at least 1600 years and possibly as much as 2300 years. Calabrian Jews have had notable influence on many areas of Jewish life and culture. The Jews of Calabria are virtually identical to the neighbouring Jews of Sicily but are considered separate. However, the Jews of Calabria and the Jews of Apulia are historically the same community, only today are considered separate. Occasionally, there is confusion with the southern Jewish community in Calabria and the northern Jewish community in Reggio Emilia. Both communities have always been entirely separate.