Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an early Christian nontrinitarian theological doctrine, subsequently revived in various forms, which holds that Jesus was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism, his resurrection, or his ascension. How common adoptionist views were among early Christians is debated, but it appears to have been most popular in the first, second, and third centuries. Some scholars see adoptionism as the belief of the earliest followers of Jesus, based on the epistles of Paul and other early literature. However, adoptionist views sharply declined in prominence in the fourth and fifth centuries, as Church leaders condemned it as a heresy.

Matthew the Apostle is named in the New Testament as one of the twelve apostles of Jesus. According to Christian traditions, he was also one of the four Evangelists as author of the Gospel of Matthew, and thus is also known as Matthew the Evangelist.

The Gospel of Thomas is an extra-canonical sayings gospel. It was discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in December 1945 among a group of books known as the Nag Hammadi library. Scholars speculate that the works were buried in response to a letter from Bishop Athanasius declaring a strict canon of Christian scripture. Scholars have proposed dates of composition as early as 60 AD and as late as 250 AD. Since its discovery, many scholars have seen it as evidence in support of the existence of a "Q source" which might have been very similar in its form as a collection of sayings of Jesus without any accounts of his deeds or his life and death, referred to as a sayings gospel.

Ebionites as a term refers to a Jewish Christian sect, which viewed poverty as a blessing, that existed during the early centuries of the Common Era. The Ebionites embraced an adoptionist Christology, thus understanding Jesus of Nazareth as a mere man who, by virtue of his righteousness in following the letter and spirit of the Law of Moses, was chosen by God to be the messianic “Prophet like Moses“. A majority of the Ebionites rejected as heresies the orthodox Christian beliefs in Jesus' divinity, pre-existence, virgin birth and substitutionary atonement; and therefore maintained that Jesus was born the natural son of Joseph and Mary, sought to abolish animal sacrifices by prophetic proclamation, and died as a martyr rather than as a substitute for others.

The Gospel of Peter, or the Gospel according to Peter, is an ancient text concerning Jesus Christ, only partially known today. Originally written in Koine Greek, it is considered a non-canonical gospel and was rejected as apocryphal by the Church's synods of Carthage and Rome, which established the New Testament canon. It was the first of the non-canonical gospels to be rediscovered, preserved in the dry sands of Egypt.

The Nazarenes were an early Jewish Christian sect in first-century Judaism. The first use of the term is found in the Acts of the Apostles of the New Testament, where Paul the Apostle is accused of being a ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes before the Roman procurator Antonius Felix at Caesarea Maritima by Tertullus. At that time, the term simply designated followers of Jesus of Nazareth, as the Hebrew term נוֹצְרִי, and the Arabic term نَصْرَانِي, still do.

The Gospel of the Hebrews, or Gospel according to the Hebrews, is a lost Jewish–Christian gospel. The text of the gospel is lost, with only fragments of it surviving as brief quotations by the early Church Fathers and in apocryphal writings. The fragments contain traditions of Jesus' pre-existence, incarnation, baptism, and probably of his temptation, along with some of his sayings. Distinctive features include a Christology characterized by the belief that the Holy Spirit is Jesus' Divine Mother and a first resurrection appearance to James, the brother of Jesus, showing a high regard for James as the leader of the Jewish Christian church in Jerusalem. It was probably composed in Greek in the first decades of the 2nd century, and is believed to have been used by Greek-speaking Jewish Christians in Egypt during that century.

Symmachus was a writer who translated the Old Testament into Greek. His translation was included by Origen in his Hexapla and Tetrapla, which compared various versions of the Old Testament side by side with the Septuagint. Some fragments of Symmachus's version that survive, in what remains of the Hexapla, inspire scholars to remark on the purity and idiomatic elegance of Symmachus' Greek. He was admired by Jerome, who used his work in composing the Vulgate.

The New Testament apocrypha are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.

The Gospel of the Ebionites is the conventional name given by scholars to an apocryphal gospel extant only as seven brief quotations in a heresiology known as the Panarion, by Epiphanius of Salamis; he misidentified it as the "Hebrew" gospel, believing it to be a truncated and modified version of the Gospel of Matthew. The quotations were embedded in a polemic to point out inconsistencies in the beliefs and practices of a Jewish Christian sect known as the Ebionites relative to Nicene orthodoxy.

The Gospel of the Twelve, possibly also referred to as the Gospel of the Apostles, is a lost gospel mentioned by Origen in Homilies on Luke as part of a list of heretical works.

The Letter of Jeremiah, also known as the Epistle of Jeremiah, is a deuterocanonical book of the Old Testament; this letter is attributed to Jeremiah and addressed to the Jews who were about to be carried away as captives to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar. It is included in Roman Catholic Bibles as the final chapter of the Book of Baruch. It is also included in Orthodox Bibles as a separate book, as well as in the Apocrypha of the Authorized Version.

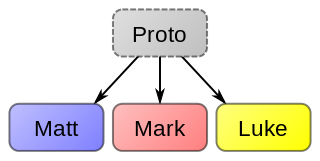

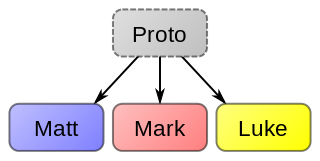

The Augustinian hypothesis is a solution to the synoptic problem, which concerns the origin of the Gospels of the New Testament. The hypothesis holds that Matthew was written first, by Matthew the Evangelist. Mark the Evangelist wrote the Gospel of Mark second and used Matthew and the preaching of Peter as sources. Luke the Evangelist wrote the Gospel of Luke and was aware of the two Gospels that preceded him. Unlike some competing hypotheses, this hypothesis does not rely on, nor does it argue for, the existence of any document that is not explicitly mentioned in historical testimony. Instead, the hypothesis draws primarily upon historical testimony, rather than textual criticism, as the central line of evidence. The foundation of evidence for the hypothesis is the writings of the Church Fathers: historical sources dating back to as early as the first half of the 2nd century, which have been held as authoritative by most Christians for nearly two millennia. Adherents to the Augustinian hypothesis view it as a simple, coherent solution to the synoptic problem.

The Old Testament is the first section of the two-part Christian biblical canon; the second section is the New Testament. The Old Testament includes the books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) or protocanon, and in various Christian denominations also includes deuterocanonical books. Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Protestants use different canons, which differ with respect to the texts that are included in the Old Testament.

The Jewish–Christian Gospels were gospels of a Jewish Christian character quoted by Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Eusebius, Epiphanius, Jerome and probably Didymus the Blind. All five call the gospel they know the "Gospel of the Hebrews", but most modern scholars have concluded that the five early church historians are not quoting the same work. As none of the works survive to this day, attempts have been made to reconstruct them from the references in the Church Fathers. The majority of scholars believe that there existed one gospel in Aramaic/Hebrew and at least two in Greek, although a minority argue that there were only two, in Aramaic/Hebrew and in Greek.

The Gospel of Basilides is the title given to a reputed text within the New Testament apocrypha, which is reported in the middle of the 3rd century as then circulating amongst the followers of Basilides (Βασιλείδης), a leading theologian of Gnostic tendencies, who had taught in Alexandria in the second quarter of the 2nd century. Basilides's teachings were condemned as heretical by Irenaeus of Lyons, and by Hippolytus of Rome, although they had been evaluated more positively by Clement of Alexandria. There is, however, no agreement amongst Irenaeus, Hippolytus or Clement as to Basilides's specific theological opinions; while none of the three report a gospel in the name of Basilides.

Nazarene is a title used to describe people from the city of Nazareth in the New Testament, and is a title applied to Jesus, who, according to the New Testament, grew up in Nazareth, a town in Galilee, located in ancient Judea. The word is used to translate two related terms that appear in the Greek New Testament: Nazarēnos ('Nazarene') and Nazōraios ('Nazorean'). The phrases traditionally rendered as "Jesus of Nazareth" can also be translated as "Jesus the Nazarene" or "Jesus the Nazorean", and the title Nazarene may have a religious significance instead of denoting a place of origin. Both Nazarene and Nazorean are irregular in Greek and the additional vowel in Nazorean complicates any derivation from Nazareth.

Traditionally in Christianity, orthodoxy and heresy have been viewed in relation to the "orthodoxy" as an authentic lineage of tradition. Other forms of Christianity were viewed as deviant streams of thought and therefore "heterodox", or heretical. This view was challenged by the publication of Walter Bauer's Rechtgläubigkeit und Ketzerei im ältesten Christentum in 1934. Bauer endeavored to rethink Early Christianity historically, independent from the views of the current church. He stated that the 2nd-century church was very diverse and included many "heretical" groups that had an equal claim to apostolic tradition. Bauer interpreted the struggle between the orthodox and heterodox to be the "mainstream" Church of Rome struggling to attain dominance. He presented Edessa and Egypt as places where the "orthodoxy" of Rome had little influence during the 2nd century. As he saw it, the theological thought of the "Orient" at the time would later be labeled "heresy". The response by modern scholars has been mixed. Some scholars clearly support Bauer's conclusions and others express concerns about his "attacking [of] orthodox sources with inquisitional zeal and exploiting to a nearly absurd extent the argument from silence." However, modern scholars have critiqued and updated Bauer's model.

The Hebrew Gospel hypothesis is that a lost gospel, written in Hebrew or Aramaic, predated the four canonical gospels. In the 18th and early 19th century several scholars suggested that a Hebrew proto-gospel was the main source or one of several sources for the canonical gospels. This theorizing would later give birth to the two source-hypothesis that views Q as a proto-gospel but believes this proto-gospel to have been written in Koine Greek. After the wide-spread scholarly acceptance of the two-source hypothesis scholarly interest in the Hebrew gospel hypothesis dwindled. Modern variants of the Hebrew gospel hypothesis survive, but have not found favor with scholars as a whole.