Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspired by models from classical antiquity and had a lasting influence on Western art. Michelangelo's creative abilities and mastery in a range of artistic arenas define him as an archetypal Renaissance man, along with his rival and elder contemporary, Leonardo da Vinci. Given the sheer volume of surviving correspondence, sketches, and reminiscences, Michelangelo is one of the best-documented artists of the 16th century. He was lauded by contemporary biographers as the most accomplished artist of his era.

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of ancient Greek and Roman thought and material culture. Stylistically, Renaissance architecture followed Gothic architecture and was succeeded by Baroque architecture and neoclassical architecture. Developed first in Florence, with Filippo Brunelleschi as one of its innovators, the Renaissance style quickly spread to other Italian cities. The style was carried to other parts of Europe at different dates and with varying degrees of impact.

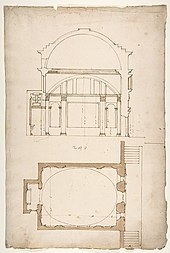

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican, or simply Saint Peter's Basilica, is a church of the Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the city of Rome, Italy. It was initially planned in the 15th century by Pope Nicholas V and then Pope Julius II to replace the ageing Old St. Peter's Basilica, which was built in the fourth century by Roman emperor Constantine the Great. Construction of the present basilica began on 18 April 1506 and was completed on 18 November 1626.

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi, commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture. He is recognized as the first modern engineer, planner, and sole construction supervisor. In 1421, Brunelleschi became the first person to receive a patent in the Western world. He is most famous for designing the dome of the Florence Cathedral, and for the mathematical technique of linear perspective in art which governed pictorial depictions of space until the late 19th century and influenced the rise of modern science. His accomplishments also include other architectural works, sculpture, mathematics, engineering, and ship design. Most surviving works can be found in Florence.

A dome is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a matter of controversy and there are a wide variety of forms and specialized terms to describe them.

Santa Maria Novella is a church in Florence, Italy, situated opposite, and lending its name to, the city's main railway station. Chronologically, it is the first great basilica in Florence, and is the city's principal Dominican church.

Florence Cathedral, formally the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower, is the cathedral of Florence, Italy. It was begun in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was structurally completed by 1436, with the dome engineered by Filippo Brunelleschi. The exterior of the basilica is faced with polychrome marble panels in various shades of green and pink, bordered by white, and has an elaborate 19th-century Gothic Revival façade by Emilio De Fabris.

A rib vault or ribbed vault is an architectural feature for covering a wide space, such as a church nave, composed of a framework of crossed or diagonal arched ribs. Variations were used in Roman architecture, Byzantine architecture, Islamic architecture, Romanesque architecture, and especially Gothic architecture. Thin stone panels fill the space between the ribs. This greatly reduced the weight and thus the outward thrust of the vault. The ribs transmit the load downward and outward to specific points, usually rows of columns or piers. This feature allowed architects of Gothic cathedrals to make higher and thinner walls and much larger windows.

The Basilica di San Lorenzo is one of the largest churches of Florence, Italy, situated at the centre of the main market district of the city, and it is the burial place of all the principal members of the Medici family from Cosimo il Vecchio to Cosimo III. It is one of several churches that claim to be the oldest in Florence, having been consecrated in 393 AD, at which time it stood outside the city walls. For three hundred years it was the city's cathedral, before the official seat of the bishop was transferred to Santa Reparata.

Giuliano da Sangallo was an Italian sculptor, architect and military engineer active during the Italian Renaissance. He is known primarily for being the favored architect of Lorenzo de' Medici, his patron. In this role, Giuliano designed a villa for Lorenzo as well as a monastery for Augustinians and a church where a miracle was said to have taken place. Additionally, Giuliano was commissioned to build multiple structures for Pope Julius II and Pope Leo X. Leon Battista Alberti and Filippo Brunelleschi heavily influenced Sangallo and in turn, he influenced other important Renaissance figures such as Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci, his brother Antonio da Sangallo the Elder, and his sons, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Francesco da Sangallo.

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, also known as Antonio Cordiani, was an Italian architect active during the Renaissance, mainly in Rome and the Papal States. One of his most popular projects that he worked on designing is St. Peter’s basilica in the Vatican City. He was also an engineer who worked on restoring several buildings. His success was greatly due to his contracts with renowned artists during his time. Sangallo died in Terni, Italy, and was buried in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Giacomo della Porta (1532–1602) was an Italian architect and sculptor, who worked on many important buildings in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica.

In architecture, a vault is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while rings of voussoirs are constructed and the rings placed in position. Until the topmost voussoir, the keystone, is positioned, the vault is not self-supporting. Where timber is easily obtained, this temporary support is provided by centering consisting of a framed truss with a semicircular or segmental head, which supports the voussoirs until the ring of the whole arch is completed.

Italy has a very broad and diverse architectural style, which cannot be simply classified by period or region, due to Italy's division into various small states until 1861. This has created a highly diverse and eclectic range in architectural designs. Italy is known for its considerable architectural achievements, such as the construction of aqueducts, temples and similar structures during ancient Rome, the founding of the Renaissance architectural movement in the late-14th to 16th century, and being the homeland of Palladianism, a style of construction which inspired movements such as that of Neoclassical architecture, and influenced the designs which noblemen built their country houses all over the world, notably in the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States of America during the late-17th to early 20th centuries.

Santa Maria delle Carceri is a basilica church, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo, and built in Prato, Tuscany, Italy. It is among the earliest examples of a Greek cross plan for a complete church in Renaissance architecture.

San Biagio is a church outside Montepulciano, Tuscany, central Italy.

Domes were a characteristic element of the architecture of Ancient Rome and of its medieval continuation, the Byzantine Empire. They had widespread influence on contemporary and later styles, from Russian and Ottoman architecture to the Italian Renaissance and modern revivals. The domes were customarily hemispherical, although octagonal and segmented shapes are also known, and they developed in form, use, and structure over the centuries. Early examples rested directly on the rotunda walls of round rooms and featured a central oculus for ventilation and light. Pendentives became common in the Byzantine period, provided support for domes over square spaces.

The early domes of the Middle Ages, particularly in those areas recently under Byzantine control, were an extension of earlier Roman architecture. The domed church architecture of Italy from the sixth to the eighth centuries followed that of the Byzantine provinces and, although this influence diminishes under Charlemagne, it continued on in Venice, Southern Italy, and Sicily. Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel is a notable exception, being influenced by Byzantine models from Ravenna and Constantinople. The Dome of the Rock, an Umayyad Muslim religious shrine built in Jerusalem, was designed similarly to nearby Byzantine martyria and Christian churches. Domes were also built as part of Muslim palaces, throne halls, pavilions, and baths, and blended elements of both Byzantine and Persian architecture, using both pendentives and squinches. The origin of the crossed-arch dome type is debated, but the earliest known example is from the tenth century at the Great Mosque of Córdoba. In Egypt, a "keel" shaped dome profile was characteristic of Fatimid architecture. The use of squinches became widespread in the Islamic world by the tenth and eleventh centuries. Bulbous domes were used to cover large buildings in Syria after the eleventh century, following an architectural revival there, and the present shape of the Dome of the Rock's dome likely dates from this time.

Domes built in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries relied primarily on empirical techniques and oral traditions rather than the architectural treatises of the time, but the study of dome structures changed radically due to developments in mathematics and the study of statics. Analytical approaches were developed and the ideal shape for a dome was debated, but these approaches were often considered too theoretical to be used in construction.