Saint Paul is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center of Minnesota's government. The Minnesota State Capitol and the state government offices all sit on a hill close to the city's downtown district. One of the oldest cities in Minnesota, Saint Paul has several historic neighborhoods and landmarks, such as the Summit Avenue Neighborhood, the James J. Hill House, and the Cathedral of Saint Paul. Like the adjacent city of Minneapolis, Saint Paul is known for its cold, snowy winters and humid summers.

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 100 BCE to 500 CE, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society but a widely dispersed set of populations connected by a common network of trade routes.

The Great Serpent Mound is a 1,348-feet-long (411 m), three-feet-high prehistoric effigy mound located in Peebles, Ohio. It was built on what is known as the Serpent Mound crater plateau, running along the Ohio Brush Creek in Adams County, Ohio. The mound is the largest serpent effigy known in the world.

Wickliffe Mounds is a prehistoric, Mississippian culture archaeological site located in Ballard County, Kentucky, just outside the town of Wickliffe, about 3 miles (4.8 km) from the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Archaeological investigations have linked the site with others along the Ohio River in Illinois and Kentucky as part of the Angel phase of Mississippian culture. Wickliffe Mounds is controlled by the State Parks Service, which operates a museum at the site for interpretation of the ancient community. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it is also a Kentucky Archeological Landmark and State Historic Site.

Little Crow III was a Mdewakanton Dakota chief who led a faction of the Dakota in a five-week war against the United States in 1862.

Frontenac State Park is a state park of Minnesota, United States, on the Mississippi River 10 miles (16 km) southeast of Red Wing. The park is notable both for its history and for its birdwatching opportunities. The centerpiece of the park is a 430-foot-high (130 m), 3-mile-long (4.8 km) steep limestone bluff overlooking Lake Pepin, a natural widening of the Mississippi. The bluff is variously called Garrard's Bluff or Point No-Point, the latter name coming from riverboat captains because of the optical illusion that it protruded into the Mississippi River. There is a natural limestone arch on the blufftop called In-Yan-Teopa, a Dakota name meaning "Rock With Opening". Park lands entirely surround the town of Frontenac, once a high-class resort at the end of the 19th century.

The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is a 72-mile (116 km) and 54,000-acre (22,000 ha) protected corridor along the Mississippi River through Minneapolis–Saint Paul in the U.S. state of Minnesota, from the cities of Dayton and Ramsey to just downstream of Hastings. This stretch of the upper Mississippi River includes natural, historical, recreational, cultural, scenic, scientific, and economic resources of national significance. This area is the only national park site dedicated exclusively to the Mississippi River. The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is sometimes abbreviated as MNRRA or MISS, the four-letter code the National Park Service assigned to the area. The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is classified as one of four national rivers in the United States, and despite its name is technically not one of the 40 national recreation areas.

An airway beacon (US) or aerial lighthouse was a rotating light assembly mounted atop a tower. These were once used extensively in the United States for visual navigation by airplane pilots along a specified airway corridor. In Europe, they were used to guide aircraft with lighted beacons at night.

The Toolesboro Mound Group, a National Historic Landmark, is a group of Havana Hopewell culture earthworks on the north bank of the Iowa River near its discharge into the Mississippi. The mounds are owned and displayed to the public by the State Historical Society of Iowa. The mound group is located east of Wapello, Iowa, near the unincorporated community of Toolesboro.

Kaposia or Kapozha was a seasonal and migratory Dakota settlement, also known as "Little Crow's village," once located on the east side of the Mississippi River in present-day Saint Paul, Minnesota. The Kaposia band of Mdewakanton Dakota was established in the late 18th century and led by a succession of chiefs known as Little Crow or "Petit Corbeau." After a flood in 1826, the band moved to the west side of the river, about nine miles below Fort Snelling.

The Sinnissippi Mounds are a Havana Hopewell culture burial mound grouping located in the city of Sterling, Illinois, United States.

Barn Bluff is a bluff along the Mississippi River in Red Wing, Minnesota, United States. The bluff is considered sacred by the Dakota people because it is the site of many burial mounds. During the 19th century, the bluff functioned as a visual reference for explorers and travelers and later served as a limestone quarry.

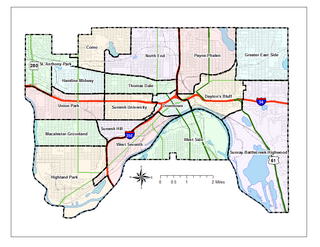

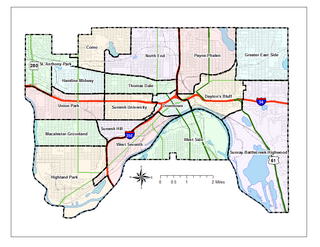

Saint Paul, Minnesota, consists of 17 officially defined city districts or neighborhoods.

Dayton's Bluff is a neighborhood located on the east side of the Mississippi River in the southeast part of the city of Saint Paul, Minnesota which has a large residential district on the plateau extending backward from its top. The name of the bluff commemorates Lyman Dayton, for whom a city in Hennepin County was also named. On the edge of the southern and highest part of Dayton's Bluff, in Indian Mounds Park, is a series of seven large aboriginal mounds, 4 to 18 feet high, that overlook the river and the central part of the city.

Saint Paul is the second largest city in the U.S. state of Minnesota, the county seat of Ramsey County, and the state capital of Minnesota. The origin and growth of the city were spurred by the proximity of Fort Snelling, the first major United States military installation in the area, as well as by the city's location on the northernmost navigable port of the Upper Mississippi River.

The Norton Mound group,, is a prehistoric Goodall focus mounds site in Wyoming, Michigan that is under the protection of the Grand Rapids Public Museum.

The Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary is a city park in the Mississippi River corridor in Saint Paul, Minnesota. Just east of the city's downtown district, the sanctuary includes towering limestone and sandstone bluffs that date back more than 450 million years, spring-fed wetlands, abundant bird life, and dramatic views of the downtown Saint Paul skyline and Mississippi River. The park was opened to the public on May 21, 2005, and was named after its early supporter U.S. Representative Bruce Vento.

The Grand Gulf Mound (22CB522) is an Early Marksville culture archaeological site located near Port Gibson in Claiborne County, Mississippi, on a bluff 1 mile (1.6 km) east of the Mississippi River, 2 miles (3.2 km) north of the mouth of the Big Black River. The site has an extant burial mound, and may have possibly had two others in the past. The site is believed to have been occupied from 50 to 200 CE. Copper objects, Marksville culture ceramics and a stone platform pipe were found in excavations at the site. The site is believed to be the only site in the Natchez Bluffs region to have been actively involved in the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. It is one of four mounds in the area believed to date to the Early Marksville period, the other three being the Marskville Mound 4 and Crooks Mounds A and B, all located in nearby Louisiana. The mound itself was built in several stages over many years, very similar to the Crooks Mound A in La Salle Parish, Louisiana. Unlike some other Hopewell sites, such as the Tremper Mound in Scioto County, Ohio, the site showed no evidence of a mortuary or communal structure previous to the construction of the mound. The beginning stage is believed to have been a rectangular earthen platform .5 feet (0.15 m) in height, 20 feet (6.1 m) wide on its east–west axis and 3.5 feet (1.1 m) long on its north–south axis. After a period of use, this platform was covered with a mantle of earth 5.5 feet (1.7 m) in height and 26.5 feet (8.1 m) wide along its east–west axis, with an extremely hard cap of earth 0.2 feet (0.061 m) covering the mound. During a third stage another mantle of earth was added to the mound, bringing it to a height of 10 feet (3.0 m) and to approximately 32 feet (9.8 m) in width on its east–west axis.

Bdóte is a significant Dakota sacred landscape where the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers meet, encompassing Pike Island, Fort Snelling, Coldwater Spring, Indian Mounds Park, and surrounding areas in present-day Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. In Dakota geographic memory, it is a single contiguous area not delineated by any contemporary areas' borders. According to Dakota oral tradition, it is the site of creation; the interconnectedness between the rivers, earth, and sky are important to the Dakota worldview and the site maintains its significance to the Dakota people.