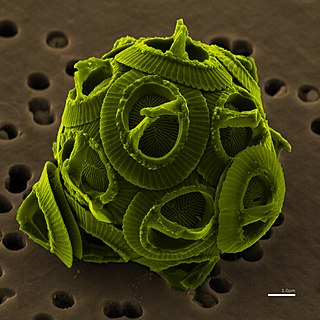

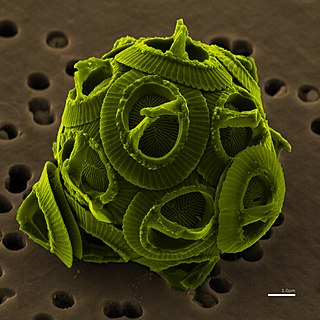

An endolith or endolithic is an organism that is able to acquire the necessary resources for growth in the inner part of a rock, mineral, coral, animal shells, or in the pores between mineral grains of a rock. Many are extremophiles, living in places long considered inhospitable to life. The distribution, biomass, and diversity of endolith microorganisms are determined by the physical and chemical properties of the rock substrate, including the mineral composition, permeability, the presence of organic compounds, the structure and distribution of pores, water retention capacity, and the pH. Normally, the endoliths colonize the areas within lithic substrates to withstand intense solar radiation, temperature fluctuations, wind, and desiccation. They are of particular interest to astrobiologists, who theorize that endolithic environments on Mars and other planets constitute potential refugia for extraterrestrial microbial communities.

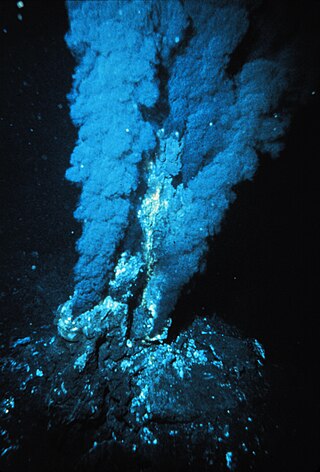

Geomicrobiology is the scientific field at the intersection of geology and microbiology and is a major subfield of geobiology. It concerns the role of microbes on geological and geochemical processes and effects of minerals and metals to microbial growth, activity and survival. Such interactions occur in the geosphere, the atmosphere and the hydrosphere. Geomicrobiology studies microorganisms that are driving the Earth's biogeochemical cycles, mediating mineral precipitation and dissolution, and sorbing and concentrating metals. The applications include for example bioremediation, mining, climate change mitigation and public drinking water supplies.

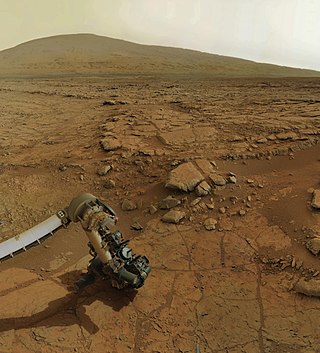

The possibility of life on Mars is a subject of interest in astrobiology due to the planet's proximity and similarities to Earth. To date, no proof of past or present life has been found on Mars. Cumulative evidence suggests that during the ancient Noachian time period, the surface environment of Mars had liquid water and may have been habitable for microorganisms, but habitable conditions do not necessarily indicate life.

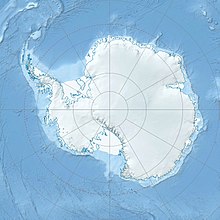

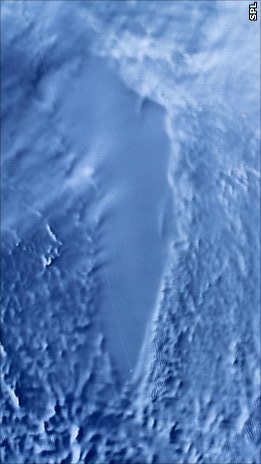

A subglacial lake is a lake that is found under a glacier, typically beneath an ice cap or ice sheet. Subglacial lakes form at the boundary between ice and the underlying bedrock, where pressure decreases the pressure melting point of ice. Over time, the overlying ice gradually melts at a rate of a few millimeters per year. Meltwater flows from regions of high to low hydraulic pressure under the ice and pools, creating a body of liquid water that can be isolated from the external environment for millions of years.

Dr Christopher P. McKay is an American planetary scientist at NASA Ames Research Center, studying planetary atmospheres, astrobiology, and terraforming. McKay majored in physics at Florida Atlantic University, where he also studied mechanical engineering, graduating in 1975, and received his PhD in astrogeophysics from the University of Colorado in 1982.

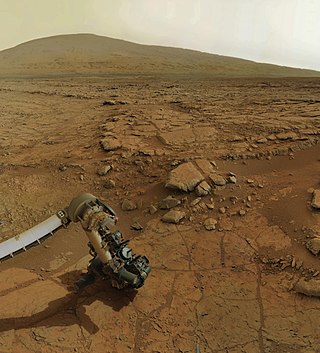

The geology of Mars is the scientific study of the surface, crust, and interior of the planet Mars. It emphasizes the composition, structure, history, and physical processes that shape the planet. It is analogous to the field of terrestrial geology. In planetary science, the term geology is used in its broadest sense to mean the study of the solid parts of planets and moons. The term incorporates aspects of geophysics, geochemistry, mineralogy, geodesy, and cartography. A neologism, areology, from the Greek word Arēs (Mars), sometimes appears as a synonym for Mars's geology in the popular media and works of science fiction. The term areology is also used by the Areological Society.

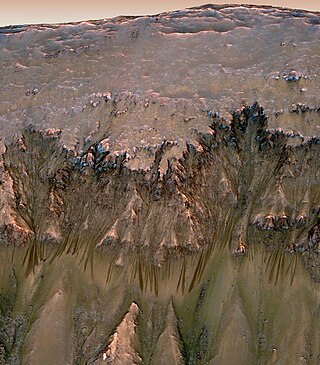

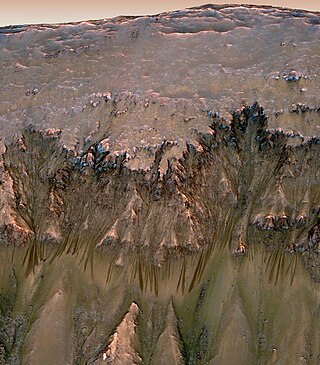

Almost all water on Mars today exists as ice, though it also exists in small quantities as vapor in the atmosphere. What was thought to be low-volume liquid brines in shallow Martian soil, also called recurrent slope lineae, may be grains of flowing sand and dust slipping downhill to make dark streaks. While most water ice is buried, it is exposed at the surface across several locations on Mars. In the mid-latitudes, it is exposed by impact craters, steep scarps and gullies. Additionally, water ice is also visible at the surface at the north polar ice cap. Abundant water ice is also present beneath the permanent carbon dioxide ice cap at the Martian south pole. More than 5 million km3 of ice have been detected at or near the surface of Mars, enough to cover the whole planet to a depth of 35 meters (115 ft). Even more ice might be locked away in the deep subsurface. Some liquid water may occur transiently on the Martian surface today, but limited to traces of dissolved moisture from the atmosphere and thin films, which are challenging environments for known life. No evidence of present-day liquid water has been discovered on the planet's surface because under typical Martian conditions, warming water ice on the Martian surface would sublime at rates of up to 4 meters per year. Before about 3.8 billion years ago, Mars may have had a denser atmosphere and higher surface temperatures, potentially allowing greater amounts of liquid water on the surface, possibly including a large ocean that may have covered one-third of the planet. Water has also apparently flowed across the surface for short periods at various intervals more recently in Mars' history. Aeolis Palus in Gale Crater, explored by the Curiosity rover, is the geological remains of an ancient freshwater lake that could have been a hospitable environment for microbial life. The present-day inventory of water on Mars can be estimated from spacecraft images, remote sensing techniques, and surface investigations from landers and rovers. Geologic evidence of past water includes enormous outflow channels carved by floods, ancient river valley networks, deltas, and lakebeds; and the detection of rocks and minerals on the surface that could only have formed in liquid water. Numerous geomorphic features suggest the presence of ground ice (permafrost) and the movement of ice in glaciers, both in the recent past and present. Gullies and slope lineae along cliffs and crater walls suggest that flowing water continues to shape the surface of Mars, although to a far lesser degree than in the ancient past.

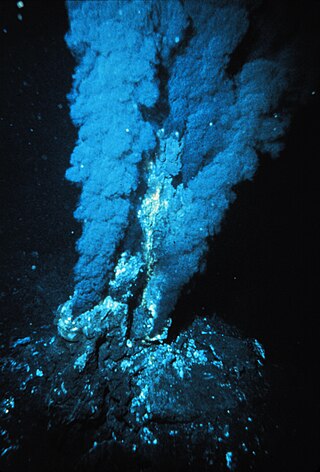

Blood Falls is an outflow of an iron oxide–tainted plume of saltwater, flowing from the tongue of Taylor Glacier onto the ice-covered surface of West Lake Bonney in the Taylor Valley of the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Victoria Land, East Antarctica.

Astrobiology Science and Technology for Exploring Planets (ASTEP) was a program established by NASA to sponsor research projects that advance the technology and techniques used in planetary exploration. The objective was to enable the study of astrobiology and to aid the planning of extraterrestrial exploration missions while prioritizing science, technology, and field campaigns.

Interplanetary contamination refers to biological contamination of a planetary body by a space probe or spacecraft, either deliberate or unintentional.

Seasonal flows on warm Martian slopes are thought to be salty water flows occurring during the warmest months on Mars, or alternatively, dry grains that "flow" downslope of at least 27 degrees.

Terrestrial analogue sites are places on Earth with assumed past or present geological, environmental or biological conditions of a celestial body such as the Moon or Mars. Analogue sites are used in the frame of space exploration to either study geological or biological processes observed on other planets, or to prepare astronauts for surface extra-vehicular activity.

Icebreaker Life is a Mars lander mission concept proposed to NASA's Discovery Program. The mission involves a stationary lander that would be a near copy of the successful 2008 Phoenix and InSight spacecraft, but would carry an astrobiology scientific payload, including a drill to sample ice-cemented ground in the northern plains to conduct a search for biosignatures of current or past life on Mars.

In summer 1965, the first close-up images from Mars showed a cratered desert with no signs of water. However, over the decades, as more parts of the planet were imaged with better cameras on more sophisticated satellites, Mars showed evidence of past river valleys, lakes and present ice in glaciers and in the ground. It was discovered that the climate of Mars displays huge changes over geologic time because its axis is not stabilized by a large moon, as Earth's is. Also, some researchers maintain that surface liquid water could have existed for periods of time due to geothermal effects, chemical composition or asteroid impacts. This article describes some of the places that could have held large lakes.

Astro microbiology, or exo microbiology, is the study of microorganisms in outer space. It stems from an interdisciplinary approach, which incorporates both microbiology and astrobiology. Astrobiology's efforts are aimed at understanding the origins of life and the search for life other than on Earth. Because microorganisms are the most widespread form of life on Earth, and are capable of colonising almost any environment, scientists usually focus on microbial life in the field of astrobiology. Moreover, small and simple cells usually evolve first on a planet rather than larger, multicellular organisms, and have an increased likelihood of being transported from one planet to another via the panspermia theory.

Signs Of LIfe Detector (SOLID) is an analytical instrument under development to detect extraterrestrial life in the form of organic biosignatures obtained from a core drill during planetary exploration.

Janice Bishop is a planetary scientist known for her research into the minerals found on Mars.

Salty subglacial lakes are controversially inferred from radar measurements to exist below the South Polar Layered Deposits (SPLD) in Ultimi Scopuli of Mars' southern ice cap. The idea of subglacial lakes due to basal melting at the polar ice caps on Mars was first hypothesized in the 1980s. For liquid water to persist below the SPLD, researchers propose that perchlorate is dissolved in the water, which lowers the freezing temperature, but other explanations such as saline ice or hydrous minerals have been offered. Challenges for explaining sufficiently warm conditions for liquid water to exist below the southern ice cap include low amounts of geothermal heating from the subsurface and overlying pressure from the ice. As a result, it is disputed whether radar detections of bright reflectors were instead caused by other materials such as saline ice or deposits of minerals such as clays. While lakes with salt concentrations 20 times that of the ocean pose challenges for life, potential subglacial lakes on Mars are of high interest for astrobiology because microbial ecosystems have been found in deep subglacial lakes on Earth, such as in Lake Whillans in Antarctica below 800 m of ice.

Salar de Pajonales is a playa in the southern Atacama Region of Chile and the third-largest in that country, behind Salar de Punta Negra and Salar de Atacama. It consists mostly of a gypsum crust; only a small portion of its area is covered with water. During the late Pleistocene, Salar de Pajonales formed an actual lake that has left shoreline features.