Tlaloc is the god of rain in Aztec religion. He was also a deity of earthly fertility and water, worshipped as a giver of life and sustenance. He was feared for his power over hail, thunder, lightning. He is also associated with caves, springs, and mountains, most specifically the sacred mountain where he was believed to reside. His cult was one of the oldest and most universal in ancient Mexico.

Teotihuacan is an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, which is located in the State of Mexico, 40 kilometers (25 mi) northeast of modern-day Mexico City. Teotihuacan is known today as the site of many of the most architecturally significant Mesoamerican pyramids built in the pre-Columbian Americas, namely the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. At its zenith, perhaps in the first half of the first millennium, Teotihuacan was the largest city in the Americas, considered as the first advanced civilization on the North American continent, with a population estimated at 125,000 or more, making it at least the sixth-largest city in the world during its epoch.

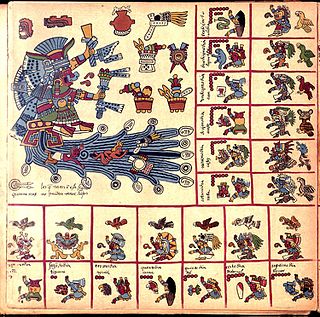

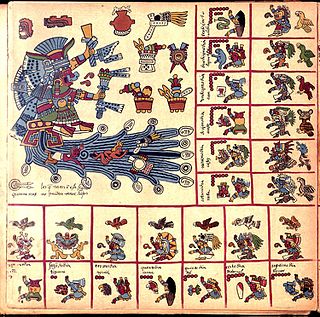

Chalchiuhtlicue[t͡ʃaːɬt͡ʃiwˈt͡ɬikʷeː] is an Aztec deity of water, rivers, seas, streams, storms, and baptism. Chalchiuhtlicue is associated with fertility, and she is the patroness of childbirth. Chalchiuhtlicue was highly revered in Aztec culture at the time of the Spanish conquest, and she was an important deity figure in the Postclassic Aztec realm of central Mexico. Chalchiuhtlicue belongs to a larger group of Aztec rain gods, and she is closely related to another Aztec water god called Chalchiuhtlatonal.

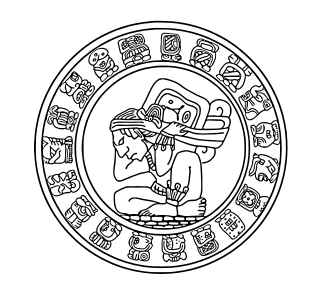

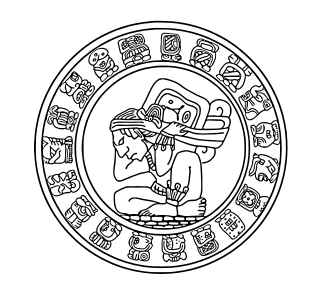

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a newer, more modern version of the game, ulama, is still played by the indigenous populations in some places.

Maya ceramics are ceramics produced in the Pre-Columbian Maya culture of Mesoamerica. The vessels used different colors, sizes, and had varied purposes. Vessels for the elite could be painted with very detailed scenes, while utilitarian vessels were undecorated or much simpler. Elite pottery, usually in the form of straight-sided beakers called "vases", used for drinking, was placed in burials, giving a number of survivals in good condition. Individual examples include the Princeton Vase and the Fenton Vase.

The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan is a proposed goddess of the pre-Columbian Teotihuacan civilization, in what is now Mexico.

Mesoamerican chronology divides the history of prehispanic Mesoamerica into several periods: the Paleo-Indian ; the Archaic, the Preclassic or Formative (2500 BCE – 250 CE), the Classic (250–900 CE), and the Postclassic (900–1521 CE); as well as the post European contact Colonial Period (1521–1821), and Postcolonial, or the period after independence from Spain (1821–present).

Mary Ellen Miller is an American art historian and academician specializing in Mesoamerica and the Maya.

Native American pottery is an art form with at least a 7500-year history in the Americas. Pottery is fired ceramics with clay as a component. Ceramics are used for utilitarian cooking vessels, serving and storage vessels, pipes, funerary urns, censers, musical instruments, ceremonial items, masks, toys, sculptures, and a myriad of other art forms.

Pre-Columbian art refers to the visual arts of indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, North, Central, and South Americas from at least 13,000 BCE to the European conquests starting in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Pre-Columbian era continued for a time after these in many places, or had a transitional phase afterwards. Many types of perishable artifacts that were no doubt once very common, such as woven textiles, typically have not been preserved, but Precolumbian monumental sculpture, metalwork in gold, pottery, and painting on ceramics, walls, and rocks have survived more frequently.

The practice of human sacrifice in pre-Columbian cultures, in particular Mesoamerican and South American cultures, is well documented both in the archaeological records and in written sources. The exact ideologies behind child sacrifice in different pre-Columbian cultures are unknown but it is often thought to have been performed to placate certain gods.

Ancient Maya art is the visual arts of the Maya civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture made up of a great number of small kingdoms in present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras. Many regional artistic traditions existed side by side, usually coinciding with the changing boundaries of Maya polities. This civilization took shape in the course of the later Preclassic Period, when the first cities and monumental architecture started to develop and the hieroglyphic script came into being. Its greatest artistic flowering occurred during the seven centuries of the Classic Period.

Maya blue is a unique bright azure blue pigment manufactured by cultures of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, such as the Mayans and Aztecs.

The Feathered Serpent was a prominent supernatural entity or deity, found in many Mesoamerican religions. It is still called Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs, Kukulkan among the Yucatec Maya, and Q'uq'umatz and Tohil among the K'iche' Maya.

The pre-Columbian history of the territory now making up the country of Mexico is known through the work of archaeologists and epigraphers, and through the accounts of Spanish conquistadores, settlers and clergymen as well as the indigenous chroniclers of the immediate post-conquest period.

Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas encompasses the visual artistic practices of the indigenous peoples of the Americas from ancient times to the present. These include works from South America and North America, which includes Central America and Greenland. The Siberian Yupiit, who have great cultural overlap with Native Alaskan Yupiit, are also included.

This is a chronological list of significant or pivotal moments in the development of Native American art or the visual arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Earlier dates, especially before the 18th century, are mostly approximate.

Esther Pasztory is a professor emerita of Pre-Columbian art history at Columbia University. From 1997 to her retirement in 2013 she held the Lisa and Bernard Selz Chair in Art History and Archaeology. Among her many publications are the first art historical manuscripts on Teotihuacan and the Aztecs. She has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship (1987–88) and a senior fellow of the board of Dumbarton Oaks.