Hadrosaurus is a genus of hadrosaurid ornithopod dinosaurs that lived in North America during the Late Cretaceous Period in what is now the Woodbury Formation about 78-80 Ma. The holotype specimen was found in fluvial marine sedimentation, meaning that the corpse of the animal was transported by a river and washed out to sea.

Claosaurus is a genus of hadrosauroid dinosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous Period (Santonian-Campanian).

The Hadrosaurus foulkii Leidy Site is a historic paleontological site in Haddonfield, Camden County, New Jersey. Now set in state-owned parkland, it is where the first relatively complete set of dinosaur bones were discovered in 1838, and then fully excavated by William Parker Foulke in 1858. The dinosaur was later named Hadrosaurus foulkii by Joseph Leidy. The site, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1994, is now a small park known as "Hadrosaurus Park" and is accessed at the eastern end of Maple Avenue in northern Haddonfield.

Paleontology in North Carolina refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U. S. state of North Carolina. Fossils are common in North Carolina. According to author Rufus Johnson, "almost every major river and creek east of Interstate 95 has exposures where fossils can be found". The fossil record of North Carolina spans from Eocambrian remains that are 600 million years old, to the Pleistocene 10,000 years ago.

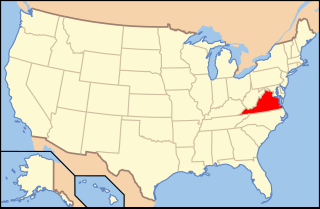

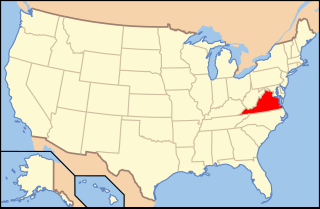

Paleontology in Virginia refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Virginia. The geologic column in Virginia spans from the Cambrian to the Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Virginia was covered by a warm shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and nautiloids. The state was briefly out of the sea during the Ordovician, but by the Silurian it was once again submerged. During this second period of inundation the state was home to brachiopods, trilobites and entire reef systems. During the mid-to-late Carboniferous the state gradually became a swampy environment.

Paleontology in Maryland refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Maryland. The invertebrate fossils of Maryland are similar to those of neighboring Delaware. For most of the early Paleozoic era, Maryland was covered by a shallow sea, although it was above sea level for portions of the Ordovician and Devonian. The ancient marine life of Maryland included brachiopods and bryozoans while horsetails and scale trees grew on land. By the end of the era, the sea had left the state completely. In the early Mesozoic, Pangaea was splitting up. The same geologic forces that divided the supercontinent formed massive lakes. Dinosaur footprints were preserved along their shores. During the Cretaceous, the state was home to dinosaurs. During the early part of the Cenozoic era, the state was alternatingly submerged by sea water or exposed. During the Ice Age, mastodons lived in the state.

Paleontology in Pennsylvania refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The geologic column of Pennsylvania spans from the Precambrian to Quaternary. During the early part of the Paleozoic, Pennsylvania was submerged by a warm, shallow sea. This sea would come to be inhabited by creatures like brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, graptolites, and trilobites. The armored fish Palaeaspis appeared during the Silurian. By the Devonian the state was home to other kinds of fishes. On land, some of the world's oldest tetrapods left behind footprints that would later fossilize. Some of Pennsylvania's most important fossil finds were made in the state's Devonian rocks. Carboniferous Pennsylvania was a swampy environment covered by a wide variety of plants. The latter half of the period was called the Pennsylvanian in honor of the state's rich contemporary rock record. By the end of the Paleozoic the state was no longer so swampy. During the Mesozoic the state was home to dinosaurs and other kinds of reptiles, who left behind fossil footprints. Little is known about the early to mid Cenozoic of Pennsylvania, but during the Ice Age it seemed to have a tundra-like environment. Local Delaware people used to smoke mixtures of fossil bones and tobacco for good luck and to have wishes granted. By the late 1800s Pennsylvania was the site of formal scientific investigation of fossils. Around this time Hadrosaurus foulkii of neighboring New Jersey became the first mounted dinosaur skeleton exhibit at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The Devonian trilobite Phacops rana is the Pennsylvania state fossil.

Paleontology in Delaware refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Delaware. There are no local rocks of Precambrian, Paleozoic, Triassic, or Jurassic age, so Delaware's fossil record does not begin until the Cretaceous period. As the Early Cretaceous gave way to the Late Cretaceous, Delaware was being gradually submerged by the sea. Local marine life included cephalopods like Belemnitella americana, and marine reptiles. The dwindling local terrestrial environments were home to a variety of plants, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs. Along with New Jersey, Delaware is one of the best sources of Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils in the eastern United States. Delaware was still mostly covered by sea water through the Cenozoic era. Local marine life included manatees, porpoises, seals, and whales. Delaware was worked over by glaciers during the Ice Age. The Cretaceous belemnite Belemnitella americana is the Delaware state fossil.

Paleontology in Connecticut refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Connecticut. Apart from its famous dinosaur tracks, the fossil record in Connecticut is relatively sparse. The oldest known fossils in Connecticut date back to the Triassic period. At the time, Pangaea was beginning to divide and local rift valleys became massive lakes. A wide variety of vegetation, invertebrates and reptiles are known from Triassic Connecticut. During the Early Jurassic local dinosaurs left behind an abundance of footprints that would later fossilize.

Paleontology in Massachusetts refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Massachusetts. The fossil record of Massachusetts is very similar to that of neighboring Connecticut. During the early part of the Paleozoic era, Massachusetts was covered by a warm shallow sea, where brachiopods and trilobites would come to live. No Carboniferous or Permian fossils are known from the state. During the Cretaceous period the area now occupied by the Elizabeth Islands and Martha's Vineyard were a coastal plain vegetated by flowers and pine trees at the edge of a shallow sea. No rocks are known of Paleogene or early Neogene age in the state, but during the Pleistocene evidence indicates that the state was subject to glacial activity and home to mastodons. The local fossil theropod footprints of Massachusetts may have been at least a partial inspiration for the Tuscarora legend of the Mosquito Monster or Great Mosquito in New York. Local fossils had already caught the attention of scientists by 1802 when dinosaur footprints were discovered in the state. Other notable discoveries include some of the first known fossil of primitive sauropodomorphs and Podokesaurus. Dinosaur tracks are the Massachusetts state fossil.

Paleontology in Arkansas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Arkansas. The fossil record of Arkansas spans from the Ordovician to the Eocene. Nearly all of the state's fossils have come from ancient invertebrate life. During the early Paleozoic, much of Arkansas was covered by seawater. This sea would come to be home to creatures including Archimedes, brachiopods, and conodonts. This sea would begin its withdrawal during the Carboniferous, and by the Permian the entire state was dry land. Terrestrial conditions continued into the Triassic, but during the Jurassic, another sea encroached into the state's southern half. During the Cretaceous the state was still covered by seawater and home to marine invertebrates such as Belemnitella. On land the state was home to long necked sauropod dinosaurs, who left behind footprints and ostrich dinosaurs such as Arkansaurus.

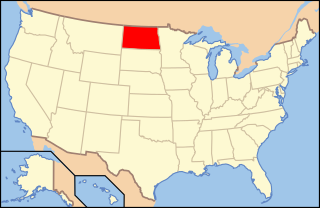

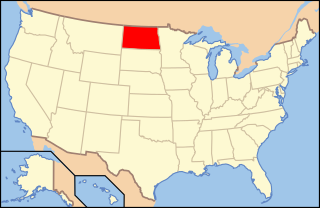

Paleontology in North Dakota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of North Dakota. During the early Paleozoic era most of North Dakota was covered by a sea home to brachiopods, corals, and fishes. The sea briefly left during the Silurian, but soon returned, until once more starting to withdraw during the Permian. By the Triassic some areas of the state were still under shallow seawater, but others were dry and hot. During the Jurassic subtropical forests covered the state. North Dakota was always at least partially under seawater during the Cretaceous. On land Sequoia grew. Later in the Cenozoic the local seas dried up and were replaced by subtropical swamps. Climate gradually cooled until the Ice Age, when glaciers entered the area and mammoths and mastodons roamed the local woodlands.

Paleontology in Texas refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Texas. Author Marian Murray has remarked that "Texas is as big for fossils as it is for everything else." Some of the most important fossil finds in United States history have come from Texas. Fossils can be found throughout most of the state. The fossil record of Texas spans almost the entire geologic column from Precambrian to Pleistocene. Shark teeth are probably the state's most common fossil. During the early Paleozoic era Texas was covered by a sea that would later be home to creatures like brachiopods, cephalopods, graptolites, and trilobites. Little is known about the state's Devonian and early Carboniferous life. However, evidence indicates that during the late Carboniferous the state was home to marine life, land plants and early reptiles. During the Permian, the seas largely shrank away, but nevertheless coral reefs formed in the state. The rest of Texas was a coastal plain inhabited by early relatives of mammals like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus. During the Triassic, a great river system formed in the state that was inhabited by crocodile-like phytosaurs. Little is known about Jurassic Texas, but there are fossil aquatic invertebrates of this age like ammonites in the state. During the Early Cretaceous local large sauropods and theropods left a great abundance of footprints. Later in the Cretaceous, the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway and home to creatures like mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and few icthyosaurs. Early Cenozoic Texas still contained areas covered in seawater where invertebrates and sharks lived. On land the state would come to be home to creatures like glyptodonts, mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, giant ground sloths, titanotheres, uintatheres, and dire wolves. Archaeological evidence suggests that local Native Americans knew about local fossils. Formally trained scientists were already investigating the state's fossils by the late 1800s. In 1938, a major dinosaur footprint find occurred near Glen Rose. Pleurocoelus was the Texas state dinosaur from 1997 to 2009, when it was replaced by Paluxysaurus jonesi after the Texan fossils once referred to the former species were reclassified to a new genus.

Paleontology in Wyoming includes research into the prehistoric life of the U.S. state of Wyoming as well as investigations conducted by Wyomingite researchers and institutions into ancient life occurring elsewhere.

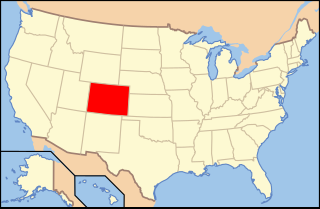

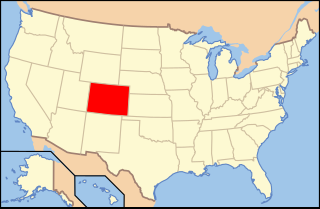

Paleontology in Colorado refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Colorado. The geologic column of Colorado spans about one third of Earth's history. Fossils can be found almost everywhere in the state but are not evenly distributed among all the ages of the state's rocks. During the early Paleozoic, Colorado was covered by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, conodonts, ostracoderms, sharks and trilobites. This sea withdrew from the state between the Silurian and early Devonian leaving a gap in the local rock record. It returned during the Carboniferous. Areas of the state not submerged were richly vegetated and inhabited by amphibians that left behind footprints that would later fossilize. During the Permian, the sea withdrew and alluvial fans and sand dunes spread across the state. Many trace fossils are known from these deposits.

Paleontology in New Mexico refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New Mexico. The fossil record of New Mexico is exceptionally complete and spans almost the entire stratigraphic column. More than 3,300 different kinds of fossil organisms have been found in the state. Of these more than 700 of these were new to science and more than 100 of those were type species for new genera. During the early Paleozoic, southern and western New Mexico were submerged by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, cartilaginous fishes, corals, graptolites, nautiloids, placoderms, and trilobites. During the Ordovician the state was home to algal reefs up to 300 feet high. During the Carboniferous, a richly vegetated island chain emerged from the local sea. Coral reefs formed in the state's seas while terrestrial regions of the state dried and were home to sand dunes. Local wildlife included Edaphosaurus, Ophiacodon, and Sphenacodon.

Paleontology in Utah refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Utah. Utah has a rich fossil record spanning almost all of the geologic column. During the Precambrian, the area of northeastern Utah now occupied by the Uinta Mountains was a shallow sea which was home to simple microorganisms. During the early Paleozoic Utah was still largely covered in seawater. The state's Paleozoic seas would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, fishes, and trilobites. During the Permian the state came to resemble the Sahara desert and was home to amphibians, early relatives of mammals, and reptiles. During the Triassic about half of the state was covered by a sea home to creatures like the cephalopod Meekoceras, while dinosaurs whose footprints would later fossilize roamed the forests on land. Sand dunes returned during the Early Jurassic. During the Cretaceous the state was covered by the sea for the last time. The sea gave way to a complex of lakes during the Cenozoic era. Later, these lakes dissipated and the state was home to short-faced bears, bison, musk oxen, saber teeth, and giant ground sloths. Local Native Americans devised myths to explain fossils. Formally trained scientists have been aware of local fossils since at least the late 19th century. Major local finds include the bonebeds of Dinosaur National Monument. The Jurassic dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis is the Utah state fossil.

Paleontology in the United States refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the United States. Paleontologists have found that at the start of the Paleozoic era, what is now "North" America was actually in the southern hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas. Later the seas were largely replaced by swamps, home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.

The geological history of North America comprises the history of geological occurrences and emergence of life in North America during the interval of time spanning from the formation of the Earth through to the emergence of humanity and the start of prehistory. At the start of the Paleozoic era, what is now "North" America was actually in the southern hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas, although terrestrial life had not yet evolved. During the latter part of the Paleozoic, seas were largely replaced by swamps home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.

The history of paleontology in the United States refers to the developments and discoveries regarding fossils found within or by people from the United States of America. Local paleontology began informally with Native Americans, who have been familiar with fossils for thousands of years. They both told myths about them and applied them to practical purposes. African slaves also contributed their knowledge; the first reasonably accurate recorded identification of vertebrate fossils in the new world was made by slaves on a South Carolina plantation who recognized the elephant affinities of mammoth molars uncovered there in 1725. The first major fossil discovery to attract the attention of formally trained scientists were the Ice Age fossils of Kentucky's Big Bone Lick. These fossils were studied by eminent intellectuals like France's George Cuvier and local statesmen and frontiersman like Daniel Boone, Benjamin Franklin, William Henry Harrison, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington. By the end of the 18th century possible dinosaur fossils had already been found.