Related Research Articles

A pension is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments. A pension may be a "defined benefit plan", where a fixed sum is paid regularly to a person, or a "defined contribution plan", under which a fixed sum is invested that then becomes available at retirement age. Pensions should not be confused with severance pay; the former is usually paid in regular amounts for life after retirement, while the latter is typically paid as a fixed amount after involuntary termination of employment before retirement.

In the United States, Social Security is the commonly used term for the federal Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program and is administered by the Social Security Administration. The original Social Security Act was enacted in 1935, and the current version of the Act, as amended, encompasses several social welfare and social insurance programs.

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance programs which provide support only to those who have previously contributed, as opposed to social assistance programs which provide support on the basis of need alone. The International Labour Organization defines social security as covering support for those in old age, support for the maintenance of children, medical treatment, parental and sick leave, unemployment and disability benefits, and support for sufferers of occupational injury.

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a compulsory governmental insurance system, not taxes on individual citizens. Depending on the jurisdiction and the status of the person, those sums may be small, covering only basic needs, or may compensate the lost time proportionally to the previous earned salary.

Social welfare, assistance for the ill or otherwise disabled and the old, has long been provided in Japan by both the government and private companies. Beginning in the 1920s, the Japanese government enacted a series of welfare programs, based mainly on European models, to provide medical care and financial support. During the post-war period, a comprehensive system of social security was gradually established.

The Mexican Institute of Social Security is a governmental organization that assists public health, pensions and social security in Mexico operating under the Secretariat of Health. It also forms an integral part of the Mexican healthcare system.

The Italian welfare state is based partly upon the corporatist-conservative model and partly upon the universal welfare model.

The Chile pension system refers to old-age, disability and survivor pensions for workers in Chile. The pension system was changed by José Piñera, during Augusto Pinochet's dictatorship, on November 4, 1980 from a PAYGO-system to a fully funded capitalization system run by private sector pension funds. Many critics and supporters see the reform as an important experiment under real conditions, that may give conclusions about the impact of the full conversion of a PAYGO-system to a capital funded system. The development was therefore internationally observed with great interest. Under Michelle Bachelet's government the Chile Pension system was reformed again.

The Mexican Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers or Civil Service Social Security and Services Institute is a federal government organization in Mexico that administers part of Mexico's health care and social security systems, and provides assistance in cases of disability, old age, early retirement, and death to federal workers. Unlike the Mexican Social Security Institute, which covers workers in the private sector, the ISSSTE is charged with providing benefits for federal government workers only. Together with the IMSS, the ISSSTE provides health coverage for between 55 and 60 percent of the population of Mexico.

Welfare in France includes all systems whose purpose is to protect people against the financial consequences of social risks.

Defined benefit (DB) pension plan is a type of pension plan in which an employer/sponsor promises a specified pension payment, lump-sum, or combination thereof on retirement that depends on an employee's earnings history, tenure of service and age, rather than depending directly on individual investment returns. Traditionally, many governmental and public entities, as well as a large number of corporations, provide defined benefit plans, sometimes as a means of compensating workers in lieu of increased pay.

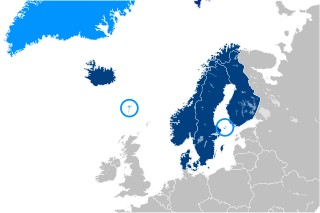

Social security or welfare in Finland is very comprehensive compared to what almost all other countries provide. In the late 1980s, Finland had one of the world's most advanced welfare systems, which guaranteed decent living conditions to all Finns. Since then social security has been cut back, but the system is still one of the most comprehensive in the world. Created almost entirely during the first three decades after World War II, the social security system was an outgrowth of the traditional Nordic belief that the state is not inherently hostile to the well-being of its citizens and can intervene benevolently on their behalf. According to some social historians, the basis of this belief was a relatively benign history that had allowed the gradual emergence of a free and independent peasantry in the Nordic countries and had curtailed the dominance of the nobility and the subsequent formation of a powerful right wing. Finland's history was harsher than the histories of the other Nordic countries but didn't prevent the country from following their path of social development.

The National Social Security Administration is a decentralized Argentine Government social insurance agency managed under the aegis of the Ministry of Health and Social Development. The agency is the principal administrator of social security and other social benefits in Argentina, including family and childhood subsidies, and unemployment insurance.

As the unemployed according to the art. 2 of the Ukrainian Law on Employment of Population are qualified citizens capable of work and of employable age, who, due to lack of a job, do not have any income or other earnings laid down by the law and are registered in the State Employment Center as looking for work, ready and able to start working. This definition also includes persons with disabilities who have not attained retirement age and are registered as seeking employment.

Luxembourg has an extensive welfare system. It comprises a social security, health, and pension funds. The labour market is highly regulated, and Luxembourg is a corporatist welfare state. Enrollment is mandatory in one of the welfare schemes for any employed person. Luxembourg's social security system is the Centre Commun de la Securite Sociale (CCSS). Both employees and employers make contributions to the fund at a rate of 25% of total salary, which cannot eclipse more than five times the minimum wage. Social spending accounts for 21.8% of GDP.

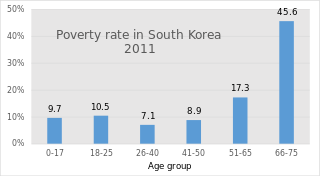

South Korea's pension scheme was introduced relatively recently, compared to other democratic nations. Half of the country's population aged 65 and over lives in relative poverty, or nearly four times the 13% average for member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). This makes old age poverty an urgent social problem. Public social spending by general government is half the OECD average, and is the lowest as a percentage of GDP among OECD member countries.

Pensions in Denmark consist of both private and public programs, all managed by the Agency for the Modernisation of Public Administration under the Ministry of Finance. Denmark created a multipillar system, consisting of an unfunded social pension scheme, occupational pensions, and voluntary personal pension plans. Denmark's system is a close resemblance to that encouraged by the World Bank in 1994, emphasizing the international importance of establishing multifaceted pension systems based on public old-age benefit plans to cover the basic needs of the elderly. The Danish system employed a flat-rate benefit funded by the government budget and available to all Danish residents. The employment-based contribution plans are negotiated between employers and employees at the individual firm or profession level, and cover individuals by labor market systems. These plans have emerged as a result of the centralized wage agreements and company policies guaranteeing minimum rates of interest. The last pillar of the Danish pension system is income derived from tax-subsidized personal pension plans, established with life insurance companies and banks. Personal pensions are inspired by tax considerations, desirable to people not covered by the occupational scheme.

The pensions system in Austria is composed of three parts: occupational pensions, private pensions, and state pensions. However, private and occupational pensions are secondary to the public pension issued through the state. According to the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), Austria's pension system is categorized as targeted. This means that their system is set up to prefentially benefit poorer pensioners than those that are better off.

Public pensions in Greece are designed to provide incomes to Greek pensioners upon reaching retirement. For decades pensions in Greece were known to be among the most generous in the European Union, allowing many pensioners to retire earlier than pensioners in other European countries. This placed a heavy burden on Greece's public finances which made the Greek state increasingly vulnerable to external economic shocks, culminating in a recession due to the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent European debt crisis. This series of crises has forced the Greek government to implement economic reforms aimed at restructuring the pension system and eliminating inefficiencies within it. Measures in the Greek austerity packages imposed upon Greek citizens by the European Central Bank have achieved some success at reforming the pension system despite having stark ramifications for standards of living in Greece, which have seen a sharp decline since the beginning of the crisis.

The Guatemalan Institute of Social Security is the branch of the Guatemalan Ministry of Work and Social Provision that provides Hospital and Clinical services; pensions and income protection benefits, and employment counseling for salaried employees in Guatemala.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "UPDATE 1-Mexican Congress passes major reform to boost pensions". Reuters. December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Marier, Patrik, and Jean F. Mayer (2007). "Welfare retrenchment as social justice: pension reform in Mexico". Journal of Social Policy. 36 (4): 585–604. doi:10.1017/S0047279407001195. S2CID 154879771.

- 1 2 3 Dion, Michelle (2009). "Globalization, Democracy, and Mexican Welfare". Comparative Politics. 42 (1): 63–82. doi:10.5129/001041509X12911362972836.

- 1 2 3 Madrid, Raul (2002). "The Politics and Economics of Pension Privatization in Latin America". Latin American Research Review. 37 (2): 159–182.

- 1 2 Dion, Michelle (2006). "Women's welfare and social security privatization in Mexico". Social Politics. 13 (3): 400–426. doi:10.1093/sp/jxl001.

- ↑ Laurell, Asa Cristina (2015). "Three Decades of Neoliberalism in Mexico: The Destruction of Society". International Journal of Health Services. 45 (2): 246–264. doi:10.1177/0020731414568507. PMID 25813500. S2CID 35915954.

- ↑ Laurell, Asa Cristina (2000). "Structural Adjustment and the Globalization of Social Policy in Latin America". International Sociology. 15 (2): 306–325. doi:10.1177/0268580900015002010. S2CID 154493926.

- ↑ Arza, Camila (2012). "Pension reforms and gender equality in Latin America". UNRISD Gender and Development Programme Paper.