Water supply and sanitation in Mexico is characterized by achievements and challenges. Among the achievements is a significant increase in access to piped water supply in urban areas as well as in rural areas between 1990 and 2010. Additionally, a strong nationwide increase in access to improved sanitation was observed in the same period. Other achievements include the existence of a functioning national system to finance water and sanitation infrastructure with a National Water Commission as its apex institution; and the existence of a few well-performing utilities such as Aguas y Drenaje de Monterrey.

Water resources and irrigation infrastructure in Peru vary throughout the country. The coastal region, an arid but fertile land, has about two-thirds of Peru's irrigation infrastructure due to private and public investment aimed at increasing agricultural exports. The Highlands and Amazon regions, with abundant water resources but rudimentary irrigation systems, are home to the majority of Peru's poor, many of whom rely on subsistence or small-scale farming.

While Peru accounts for about four per cent of the world's annual renewable water resources, over 98% of its water is available east of the Andes, in the Amazon region. The coastal area of Peru, with most of economic activities and more than half of the population, receives only 1.8% of the national freshwater renewable water resources. Economic and population growth are taking an increasing toll on water resources quantity and quality, especially in the coastal area of Peru.

Water resources management is a significant challenge for Mexico. The country has in place a system of water resources management that includes both central (federal) and decentralized institutions. Furthermore, water management is imposing a heavy cost to the economy.

Irrigation in Brazil has been developed through the use of different models. Public involvement in irrigation is relatively new while private investment has traditionally been responsible for irrigation development. Private irrigation predominates in the populated South, Southeast, and Center-West regions with most of the country’s agricultural and industrial development. In the Northeast region, investments made by the public sector seek to stimulate regional development in an area prone to droughts and with serious social problems. These different approaches have resulted in diverse outcomes. Of the 120 million hectares (ha) that are potentially available for agriculture, only about 3.5 million ha are under irrigation, although estimates show that 29 million ha are suitable for this practice.

Bolivia’s government considers irrigated agriculture as a major contributor to "better quality of life, rural and national development." After a period of social unrest caused by the privatization of water supply in Cochabamba and La Paz, the government of Evo Morales is undertaking a major institutional reform in the water resources management and particularly in the irrigation sector, aimed at: (i) including indigenous and rural communities in decision making, (ii) integrating technical and traditional knowledge on water resources management and irrigation, (iii) granting and registering water rights, (iv) increasing efficiency of irrigation infrastructure, (v) enhancing water quality, and (v) promoting necessary investment and financial sustainability in the sector. Bolivia is the first country in Latin America with a ministry dedicated exclusively to integrated water resources management: the Water Ministry.

Bolivia has traditionally undertaken different water resources management approaches aimed at alleviating political and institutional instability in the water sector. The so-called water wars of 2000 and 2006 in Cochabamba and El Alto, respectively, added social unrest and conflict into the difficulties of managing water resources in Bolivia. Evo Morales’ administration is currently developing an institutional and legal framework aimed at increasing participation, especially for rural and indigenous communities, and separating the sector from previous privatization policies. In 2009, the new Environment and Water Resources Ministry was created absorbing the responsibilities previously under the Water Ministry. The Bolivian Government is in the process of creating a new Water Law – the current Water Law was created in 1906 – and increasing much needed investment on hydraulic infrastructure.

Irrigation in Colombia has been an integral part of Colombia's agricultural and rural development in the 20th Century. Public investment in irrigation has been especially prominent in the first half of the Century. During the second half, largely driven by fiscal shortages and a common inability to raise sufficient revenues from collection of water charges, the Colombian government adopted a program to devolve irrigation management responsibility to water users associations. Irrigation management transfer has occurred only partially in Colombia, as the government has maintained strong managerial tasks in certain irrigation districts.

The water resources management system in Uruguay has been influenced by the general sense of water as an abundant resource in the country. Average annual rainfall is 1,182 mm, representing a contribution of 210 km3 annually throughout its territory. In 2002, the per capita renewable water resources was 41,065 cubic meters, way above the world average 8,467 m3 in 2006. Uruguay also shares one of the largest groundwater reserves in the world, the Guarani Aquifer, with Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay. The Guarani aquifer covers 1,200,000 square kilometers and has a storage capacity of 40,000 km3.

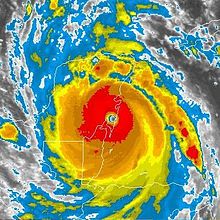

With surface water resources of 20 billion m3 per year, of which 12 billion m3 are groundwater recharge, water resources in the Dominican Republic could be considered abundant. But irregular spatial and seasonal distribution, coupled with high consumption in irrigation and urban water supply, translates into water scarcity. Rapid economic growth and increased urbanization have also affected environmental quality and placed strains on the Dominican Republic's water resources base. In addition, the Dominican Republic is exposed to a number of natural hazards, such as hurricanes, storms, floods, Drought, earthquakes, and fires. Global climate change is expected to induce permanent climate shocks to the Caribbean region, which will likely affect the Dominican Republic in the form of sea level rise, higher surface air and sea temperatures, extreme weather events, increased rainfall intensity and more frequent and more severe "El Niño-like" conditions.

Irrigation in the Dominican Republic (DR) has been an integral part of DR agricultural and economic development in the 20th century. Public investment in irrigation has been the main driver for irrigation infrastructural development in the country. Irrigation Management Transfer to Water Users Associations (WUAs), formally started in the mid-1980s, is still an ongoing process showing positive signs with irrigation systems in 127,749 ha, being managed by 41,329 users. However, the transfer process and the performance of WUAs are still far from ideal. While WUAs show a significant increase in cost recovery, especially when compared to low values in areas under state management, a high subsidy from the government still contributes to cover operation and maintenance costs in their systems.

Greater Mexico City, a metropolitan area with more than 19 million inhabitants including Mexico's capital with about 9 million inhabitants, faces tremendous water challenges. These include groundwater overexploitation, land subsidence, the risk of major flooding, the impacts of increasing urbanization, poor water quality, inefficient water use, a low share of wastewater treatment, health concerns about the reuse of wastewater in agriculture, and limited cost recovery. Overcoming these challenges is complicated by fragmented responsibilities for water management in Greater Mexico City:

Water resources management (WRM) in Honduras is a work in progress and at times has advanced; however, unstable investment and political climates, strong weather phenomena, poverty, lack of adequate capacity, and deficient infrastructures have and will continue to challenge developments to water resource management. The State of Honduras is working on a new General Water Law to replace the 1927 Law on Using National Waters and designed to regulate water use and management. The new water law will also create a Water Authority, and the National Council of Water Resources which will serve as an advising and consultative body.

Early in the 20th century, Monterrey, Mexico began a successful economic metamorphosis and growth pattern that remains an exception in Mexico. This all began with increased investments in irrigation that fueled a boom in agriculture and ranching for this northern Mexican city. The economic growth has fueled income disparity for the 3.86 million residents who live in the Monterrey Metro area (MMA). In addition, the rapid urbanization has taken a large toll on the water resources. In addressing many of this challenges, the city of Monterrey has become a model for sound and effective Integrated urban water management.

Irrigation is the artificial exploitation and distribution of water at project level aiming at application of water at field level to agricultural crops in dry areas or in periods of scarce rainfall to assure or improve crop production.

This article discusses organizational forms and means of management of irrigation water at project (system) level.

Costa Rica is divided into three major drainage basins encompassing 34 watersheds with numerous rivers and tributaries, one major lake used for hydroelectric generation, and two major aquifers that serve to store 90% of the municipal, industrial, and agricultural water supply needs of Costa Rica. Agriculture is the largest water user demanding around 53% of total supplies while the sector contributes 6.5% to the Costa Rica GDP. About a fifth of land under cultivation is being irrigated by surface water. Hydroelectric power generation makes up a significant portion of electricity usage in Costa Rica and much of this comes from the Arenal dam.

Water resources management in Nicaragua is carried out by the National water utility and regulated by the Nicaraguan Institute of water. Nicaragua has ample water supplies in rivers, groundwater, lagoons, and significant rainfall. Distribution of rainfall is uneven though with more rain falling on an annual basis in the Caribbean lowlands and much lower amounts falling in the inland areas. Significant water resources management challenges include contaminated surface water from untreated domestic and industrial wastewater, and poor overall management of the available water resources.

Water resources management in El Salvador is characterized by difficulties in addressing severe water pollution throughout much of the country's surface waters due to untreated discharges of agricultural, domestic and industrial run off. The river that drains the capital city of San Salvador is considered to be polluted beyond the capability of most treatment procedures.

The management of Jamaica's freshwater resources is primarily the domain and responsibility of the National Water Commission (NWC). The duties of providing service and water infrastructure maintenance for rural communities across Jamaica are shared with the Parish Councils. Where possible efficiencies have been identified, the NWC has outsourced various operations to the private sector.

Guatemala faces substantial resource and institutional challenges in successfully managing its national water resources. Deforestation is increasing as the global demand for timber exerts pressure on the forests of Guatemala. Soil erosion, runoff, and sedimentation of surface water is a result of deforestation from development of urban centers, agriculture needs, and conflicting land and water use planning. Sectors within industry are also growing and the prevalence of untreated effluents entering waterways and aquifers has grown alongside.