Legal concept in Catholic canon law

Privilege in the canon law of the Roman Catholic Church is the legal concept whereby someone is exempt from the ordinary operation of the law over time for some specific purpose.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

| |

Privilege in the canon law of the Roman Catholic Church is the legal concept whereby someone is exempt from the ordinary operation of the law over time for some specific purpose.

Papal privileges resembled dispensations, since both involved exceptions to the ordinary operations of the law. But whereas "dispensations exempt[ed] some person or group from legal obligations binding on the rest of the population or class to which they belong," [1] "[p]rivileges bestowed a positive favour not generally enjoyed by most people." "Thus licences to teach or to practise law or medicine, for example," [2] were "legal privileges, since they confer[red] upon recipients the right to perform certain functions for pay, which the rest of the population [was] not [permitted to exercise.]" [3] Privileges differed from dispensations in that dispensations were for one time, while a privilege was lasting. [4] Yet, such licenses might also involve what should properly be termed dispensation, if they waived the canon law requirement that an individual hold a particular qualification to practice law or medicine, as, for example, a degree.

The distinction between privilege and dispensation was not always clearly observed, and the term dispensation rather than privilege was used, even when the nature of the act made it clearly a privilege. Indeed, medieval canonists treated privileges and dispensations as distinct, though related, aspects of the law. Privileges and indults were both special favours. Some writers hold that the former are positive favours, while indults are negative. [5] The pope might confer a degree as a positive privilege in his capacity as a temporal sovereign, or he might do so by way of dispensation from the strict requirements of the canon law. In both cases his authority to do so was found in the canon law.

In some instances, petitioners sought an academic degree because without one they could not hold a particular office. Canons of certain cathedrals and Westminster Abbey were still required to be degree-holders until recent times. The Dean of Westminster Abbey was required to be a doctor or bachelor of divinity as recently as the late twentieth century. [6]

In the event of degree status being conferred, the recipient was not deemed to hold the degree in question but would enjoy any privileges which might be attached to such a degree—including qualification for office. Conferring the degree itself would of course mean that the recipient enjoyed the style and not merely the privileges of a degree. They might also, for example, be thereafter admitted or incorporated to the same degree ad eundum at Oxford or Cambridge—though few seem to have been so distinguished. It was however often difficult to be certain whether the degree itself, or merely its status and privileges, which was being conferred. Given the ostensible purpose of the papal dispensatory jurisdiction, it would perhaps be more logical to view all of these “degrees” as strictly degree-status, and not substantive degrees. But the medieval—if not indeed modern—concept of the degree is of a grade or status. One achieves the status of master or doctor, which is conferred by one's university (or in rare cases, by the pope). It is not an award, but the recognition of a certain degree of learning. It is perhaps significant that in the records of the (post-Reformation) Court of Faculties, the early “Lambeth degrees” are described in terms of dispensation to enjoy the privilege of DCL or whatever the degree might be. [7]

The exercise of the authority to confer such a privilege was often a positive step by the pope to emphasise his spiritual, if not temporal, authority. During the fifteenth century, attempts were made in England to restrict the exercise of papal power in opposition to the Statute of Provisors. [8] To evade the disabilities imposed by that Act on non-graduates, it became usual towards the end of the century for those clerics not educated at English universities to obtain dispensations from Rome, including, in a few cases, degrees. [9]

An Abbreviator or Breviator was a writer of the Papal Chancery who adumbrated and prepared in correct form Papal bulls, briefs, and consistorial decrees before these were written out in extenso by the scriptores.

A cardinal is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. Cardinals are created by the pope and typically hold the title for life. Collectively, they constitute the College of Cardinals.

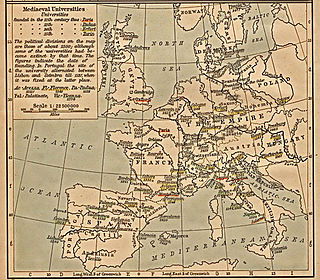

A medieval university was a corporation organized during the Middle Ages for the purposes of higher education. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities were established in present-day Italy, including the Kingdoms of Sicily and Naples, and the Kingdoms of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and Scotland between the 11th and 15th centuries for the study of the arts and the higher disciplines of theology, law, and medicine. These universities evolved from much older Christian cathedral schools and monastic schools, and it is difficult to define the exact date when they became true universities, though the lists of studia generalia for higher education in Europe held by the Vatican are a useful guide.

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarch's or the state's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope. Gallicanism is a rejection of ultramontanism; it has something in common with Anglicanism, but is nuanced, in that it plays down the authority of the Pope in church without denying that there are some authoritative elements to the office associated with being primus inter pares. Other terms for the same or similar doctrines include Erastianism, Febronianism, and Josephinism.

Studium generale is the old customary name for a medieval university in medieval Europe.

A Lambeth degree is an academic degree conferred by the Archbishop of Canterbury under the authority of the Ecclesiastical Licences Act 1533 (Eng) as successor of the papal legate in England. The degrees conferred most commonly are DD, DCL, DLitt, DMus, DM, BD and MA. The relatively modern degree of MLitt has been conferred in recent years, and the MPhil and PhD are now available.

The Ecclesiastical Licences Act 1533, also known as the Act Concerning Peter's Pence and Dispensations, is an Act of the Parliament of England. It was passed by the English Reformation Parliament in the early part of 1534 and outlawed the payment of Peter's Pence and other payments to Rome. The Act remained partly in force in Great Britain at the end of 2010. It is under section III of this Act, that the Archbishop of Canterbury can award a Lambeth degree as an academic degree.

In the Roman Catholic Church, protonotary apostolic is the title for a member of the highest non-episcopal college of prelates in the Roman Curia or, outside Rome, an honorary prelate on whom the pope has conferred this title and its special privileges. An example is Prince Georg of Bavaria (1880–1943), who became in 1926 Protonotary by papal decree.

Doctor of Civil Law is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

The Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura is the highest judicial authority in the Catholic Church. In addition, it oversees the administration of justice in the church.

In the jurisprudence of the canon law of the Catholic Church, a dispensation is the exemption from the immediate obligation of law in certain cases. Its object is to modify the hardship often arising from the rigorous application of general laws to particular cases, and its essence is to preserve the law by suspending its operation in such cases.

In the Catholic Church, a declaration of nullity, commonly called an annulment and less commonly a decree of nullity, and in some cases, a Catholic divorce, is an ecclesiastical tribunal determination and judgment that a marriage was invalidly contracted or, less frequently, a judgment that ordination was invalidly conferred.

The Apostolic Datary was one of the five Ufficii di Curia in the Roman Curia of the Roman Catholic Church. It was instituted no later than the 14th AD. Pope Paul VI abolished it in 1967.

An ecclesiastical ring is a finger ring worn by clergy, such as a bishop's ring.

The appointment of bishops in the Catholic Church is a complicated process. Outgoing bishops, neighbouring bishops, the faithful, the apostolic nuncio, various members of the Roman Curia, and the pope all have a role in the selection. The exact process varies based upon a number of factors, including whether the bishop is from the Latin Church or one of the Eastern Catholic Churches, the geographic location of the diocese, what office the candidate is being chosen to fill, and whether the candidate has previously been ordained to the episcopate.

A faculty, in the canon law of the Roman Catholic Church, is an ecclesiastical right conferred on a subordinate, by a superior who enjoys jurisdiction in the external forum. These rights then allow the subordinate to act, in the external or internal forum, validly or lawfully, or at least safely.

In the canon law of the Catholic Church, canonical provision is the regular induction into a benefice.

In the canon law of the Catholic Church, exclaustration is the official authorization for a member of a religious order bound by perpetual vows to live for a limited time outside their religious institute, usually with a view to discerning whether to depart definitively.

The jurisprudence of Catholic canon law is the complex of legal theory, traditions, and interpretative principles of Catholic canon law. In the Latin Church, the jurisprudence of canon law was founded by Gratian in the 1140s with his Decretum. In the Eastern Catholic canon law of the Eastern Catholic Churches, Photios holds a place similar to that of Gratian for the West.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the canon law of the Catholic Church: