Tarquinia, formerly Corneto, is an old city in the province of Viterbo, Lazio, Central Italy, known chiefly for its ancient Etruscan tombs in the widespread necropoleis, or cemeteries, for which it was awarded UNESCO World Heritage status.

Cerveteri is a town and comune of northern Lazio in the region of the Metropolitan City of Rome. Known by the ancient Romans as Caere, and previously by the Etruscans as Caisra or Cisra, and as Agylla by the Greeks, its modern name derives from Caere Vetus used in the 13th century to distinguish it from Caere Novum.

Caere is the Latin name given by the Romans to one of the larger cities of southern Etruria, the modern Cerveteri, approximately 50–60 kilometres north-northwest of Rome. To the Etruscans it was known as Cisra, to the Greeks as Agylla and to the Phoenicians as 𐤊𐤉𐤔𐤓𐤉𐤀.

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions is an archaeological site at the ancient city of Veii, Italy. It is best known for its well-preserved fresco paintings of four feline-like creatures, believed by archaeologists to depict lions. The tomb is believed to be one of the oldest painted tombs in the western Mediterranean, dating back to 690 BCE. The discovery of the Tomb allowed archaeologists a greater insight into funerary practices amongst the Etruscan people, while providing insight into art movements around this period of time. The fresco paintings on the wall of the tomb are a product of advances in trade that allowed artists in Veii to be exposed to art making practices and styles of drawing originating from different cultures, in particular geometric art movements in Greece. The lions were originally assumed to be caricatures of lions – created by artists who had most likely never seen the real animal in flesh before.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term encompasses a wide variety of forms, including cenotaphs, tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains, and communal memorials to the dead, such as war memorials, which may or may not contain remains, and a range of prehistoric megalithic constructs. Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the lives of the living.

In the burial practices of ancient Rome and Roman funerary art, marble and limestone sarcophagi elaborately carved in relief were characteristic of elite inhumation burials from the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD. At least 10,000 Roman sarcophagi have survived, with fragments possibly representing as many as 20,000. Although mythological scenes have been quite widely studied, sarcophagus relief has been called the "richest single source of Roman iconography," and may also depict the deceased's occupation or life course, military scenes, and other subject matter. The same workshops produced sarcophagi with Jewish or Christian imagery. Early Christian sarcophagi produced from the late 3rd century onwards, represent the earliest form of large Christian sculpture, and are important for the study of Early Christian art.

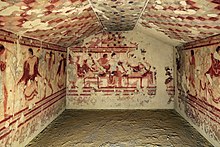

The Tomb of the Leopards is an Etruscan burial chamber so called for the confronted leopards painted above a banquet scene. The tomb is located within the Necropolis of Monterozzi, near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy, and dates to around 470–450 BC. The painting is one of the best-preserved murals of Tarquinia, and is known for "its lively coloring, and its animated depictions rich with gestures," and is influenced by the Greek-Attic art of the first quarter of the fifth century BC.

The Monterozzi necropolis is an Etruscan necropolis on a hill east of Tarquinia in Lazio, Italy. The necropolis has about 6,000 graves, the oldest of which dates to the 7th century BC. About 200 of the tomb chambers are decorated with frescos.

The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, formerly known as the Tomb of the Hunter, is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy. It was discovered in 1873 and has been dated variously to about 530–520 BC, 520 BC, 510 BC or 510–500 BC. Stephan Steingräber calls it "unquestionably one of the most beautiful and original of the Tarquinian tombs from the Late Archaic period." R. Ross Holloway emphasizes the reduction of humans to small figures in a large natural environment. There were no precedents for this in Ancient Greek art or in the Etruscan art it influenced. It was a major development in the history of ancient painting.

The Tomb of the Triclinium ) is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi dated to approximately 470 BC. The tomb is named after the Roman triclinium, a type of formal dining room, which appears in the frescoes of the tomb. It has been described as one of the most famous of all Etruscan tombs.

The Tarquinia National Museum is an archaeological museum dedicated to the Etruscan civilization in Tarquinia, Italy. Its collection consists primarily of the artifacts which were excavated from the Necropolis of Monterozzi to the east of the city. It is housed in the Palazzo Vitelleschi.

The Tomb of the Blue Demons is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Italy. It was discovered in 1985. The tomb is named after the blue and black-skinned demons which appear in an underworld scene on the right wall. The tomb has been dated to the end of the fifth century BC.

The funerary art of Ancient Rome changed throughout the course of the Roman Republic and the Empire and comprised many different forms. There were two main burial practices used by the Romans throughout history, one being cremation, another inhumation. The vessels used for these practices include sarcophagi, ash chests, urns, and altars. In addition to these, mausoleums, stele, and other monuments were also used to commemorate the dead. The method by which Romans were memorialized was determined by social class, religion, and other factors. While monuments to the dead were constructed within Roman cities, the remains themselves were interred outside the cities.

The Tomb of the Augurs is an Etruscan burial chamber so called because of a misinterpretation of one of the fresco figures on the right wall thought to be a Roman priest known as an augur. The tomb is located within the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy, and dates to around 530-520 BC. This tomb is one of the first tombs in Tarquinia to have figural decoration on all four walls of its main or only chamber. The wall decoration was frescoed between 530-520 BC by an Ionian Greek painter, perhaps from Phocaea, whose style was associated with that of the Northern Ionic workers active in Elmali. This tomb is also the first time a theme not of mythology, but instead depictions of funerary rites and funerary games are seen.

Etruscan architecture was created between about 900 BC and 27 BC, when the expanding civilization of ancient Rome finally absorbed Etruscan civilization. The Etruscans were considerable builders in stone, wood and other materials of temples, houses, tombs and city walls, as well as bridges and roads. The only structures remaining in quantity in anything like their original condition are tombs and walls, but through archaeology and other sources we have a good deal of information on what once existed.

Carved amber bow of a fibula, also known as the Morgan Amber, is a 5th-century BCE Etruscan fibula by an unknown artist. It is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Etruscan sculpture was one of the most important artistic expressions of the Etruscan people, who inhabited the regions of Northern Italy and Central Italy between about the 9th century BC and the 1st century BC. Etruscan art was largely a derivation of Greek art, although developed with many characteristics of its own. Given the almost total lack of Etruscan written documents, a problem compounded by the paucity of information on their language—still largely undeciphered—it is in their art that the keys to the reconstruction of their history are to be found, although Greek and Roman chronicles are also of great help. Like its culture in general, Etruscan sculpture has many obscure aspects for scholars, being the subject of controversy and forcing them to propose their interpretations always tentatively, but the consensus is that it was part of the most important and original legacy of Italian art and even contributed significantly to the initial formation of the artistic traditions of ancient Rome. The view of Etruscan sculpture as a homogeneous whole is erroneous, there being important variations, both regional and temporal.

Women were respected in Etruscan society compared to their ancient Greek and Roman counterparts. Today only the status of aristocratic women is known because no documentation survives about women in other social classes.

Daily life among the Etruscans is difficult to trace, as few literary testimonies are available and Etruscan historiography was highly controversial in the 19th century.