Adenocarcinoma is a type of cancerous tumor that can occur in several parts of the body. It is defined as neoplasia of epithelial tissue that has glandular origin, glandular characteristics, or both. Adenocarcinomas are part of the larger grouping of carcinomas, but are also sometimes called by more precise terms omitting the word, where these exist. Thus invasive ductal carcinoma, the most common form of breast cancer, is adenocarcinoma but does not use the term in its name—however, esophageal adenocarcinoma does to distinguish it from the other common type of esophageal cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Several of the most common forms of cancer are adenocarcinomas, and the various sorts of adenocarcinoma vary greatly in all their aspects, so that few useful generalizations can be made about them.

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a cancer that develops from the lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a number of subtypes, including gastric adenocarcinomas. Lymphomas and mesenchymal tumors may also develop in the stomach. Early symptoms may include heartburn, upper abdominal pain, nausea, and loss of appetite. Later signs and symptoms may include weight loss, yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, vomiting, difficulty swallowing, and blood in the stool, among others. The cancer may spread from the stomach to other parts of the body, particularly the liver, lungs, bones, lining of the abdomen, and lymph nodes.

A Krukenberg tumor refers to a malignancy in the ovary that metastasized from a primary site, classically the gastrointestinal tract, although it can arise in other tissues such as the breast. Gastric adenocarcinoma, especially at the pylorus, is the most common source. Krukenberg tumors are often found in both ovaries, consistent with its metastatic nature.

Carcinoma is a malignancy that develops from epithelial cells. Specifically, a carcinoma is a cancer that begins in a tissue that lines the inner or outer surfaces of the body, and that arises from cells originating in the endodermal, mesodermal or ectodermal germ layer during embryogenesis.

Linitis plastica is a morphological variant of diffuse stomach cancer in which the stomach wall becomes thick and rigid.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a clinical condition caused by cancerous cells that produce abundant mucin or gelatinous ascites. The tumors cause fibrosis of tissues and impede digestion or organ function, and if left untreated, the tumors and mucin they produce will fill the abdominal cavity. This will result in compression of organs and will destroy the function of the colon, small intestine, stomach, or other organs. Prognosis with treatment in many cases is optimistic, but the disease is lethal if untreated, with death occurring via cachexia, bowel obstruction, or other types of complications.

Invasive carcinoma of no special type, invasive breast carcinoma of no special type (IBC-NST), invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) or invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) is a disease. For international audiences this article will use "invasive carcinoma NST" because it is the preferred term of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Gastrointestinal cancer refers to malignant conditions of the gastrointestinal tract and accessory organs of digestion, including the esophagus, stomach, biliary system, pancreas, small intestine, large intestine, rectum and anus. The symptoms relate to the organ affected and can include obstruction, abnormal bleeding or other associated problems. The diagnosis often requires endoscopy, followed by biopsy of suspicious tissue. The treatment depends on the location of the tumor, as well as the type of cancer cell and whether it has invaded other tissues or spread elsewhere. These factors also determine the prognosis.

A malignant mixed Müllerian tumor, also known as malignant mixed mesodermal tumor (MMMT) is a cancer found in the uterus, the ovaries, the fallopian tubes and other parts of the body that contains both carcinomatous and sarcomatous components. It is divided into two types, homologous and a heterologous type. MMMT account for between two and five percent of all tumors derived from the body of the uterus, and are found predominantly in postmenopausal women with an average age of 66 years. Risk factors are similar to those of adenocarcinomas and include obesity, exogenous estrogen therapies, and nulliparity. Less well-understood but potential risk factors include tamoxifen therapy and pelvic irradiation.

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) of the lung —previously included in the category of "bronchioloalveolar carcinoma" (BAC)—is a subtype of lung adenocarcinoma. It tends to arise in the distal bronchioles or alveoli and is defined by a non-invasive growth pattern. This small solitary tumor exhibits pure alveolar distribution and lacks any invasion of the surrounding normal lung. If completely removed by surgery, the prognosis is excellent with up to 100% 5-year survival.

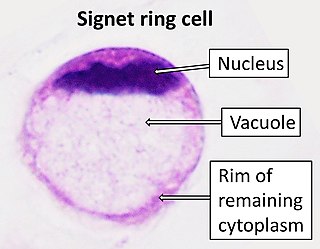

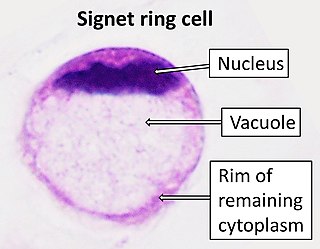

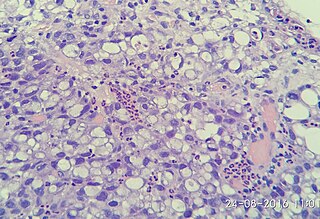

In histology, a signet ring cell is a cell with a large vacuole. The malignant type is seen predominantly in carcinomas. Signet ring cells are most frequently associated with stomach cancer, but can arise from any number of tissues including the prostate, bladder, gallbladder, breast, colon, ovarian stroma and testis.

Urachal cancer is a very rare type of cancer arising from the urachus or its remnants. The disease might arise from metaplastic glandular epithelium or embryonic epithelial remnants originating from the cloaca region.

Cancer of unknown primary origin (CUP) is a cancer that is determined to be at the metastatic stage at the time of diagnosis, but a primary tumor cannot be identified. A diagnosis of CUP requires a clinical picture consistent with metastatic disease and one or more biopsy results inconsistent with a tumor cancer

Uterine clear-cell carcinoma (CC) is a rare form of endometrial cancer with distinct morphological features on pathology; it is aggressive and has high recurrence rate. Like uterine papillary serous carcinoma CC does not develop from endometrial hyperplasia and is not hormone sensitive, rather it arises from an atrophic endometrium. Such lesions belong to the type II endometrial cancers.

HOHMS is the medical acronym for "Higher-Order HistoMolecular Stratification", a term and concept which was first applied to lung cancer research and treatment theory.

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of the lung (MCACL) is a very rare malignant mucus-producing neoplasm arising from the uncontrolled growth of transformed epithelial cells originating in lung tissue.

Adenocarcinoma of the lung is the most common type of lung cancer, and like other forms of lung cancer, it is characterized by distinct cellular and molecular features. It is classified as one of several non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), to distinguish it from small cell lung cancer which has a different behavior and prognosis. Lung adenocarcinoma is further classified into several subtypes and variants. The signs and symptoms of this specific type of lung cancer are similar to other forms of lung cancer, and patients most commonly complain of persistent cough and shortness of breath.

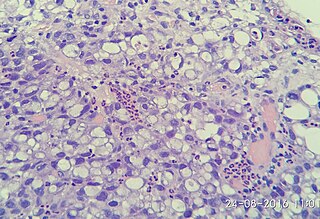

Poorly cohesive gastric carcinoma is a malignant tumour of epithelial origin, characterized by diffuse distribution of tumour cells, isolated from each other or in small groups.

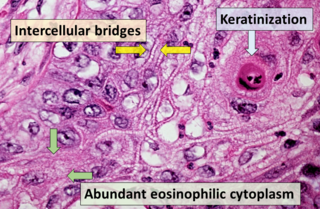

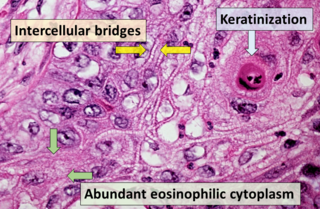

Squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC), also known as epidermoid carcinoma, comprises a number of different types of cancer that begin in squamous cells. These cells form on the surface of the skin, on the lining of hollow organs in the body, and on the lining of the respiratory and digestive tracts.

The histopathology of colorectal cancer of the adenocarcinoma type involves analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. A pathology report contains a description of the microscopical characteristics of the tumor tissue, including both tumor cells and how the tumor invades into healthy tissues and finally if the tumor appears to be completely removed. The most common form of colon cancer is adenocarcinoma, constituting between 95% and 98% of all cases of colorectal cancer. Other, rarer types include lymphoma, adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma. Some subtypes have been found to be more aggressive.