Lillooet is a district municipality in the Squamish-Lillooet region of southwestern British Columbia. The town is on the west shore of the Fraser River immediately north of the Seton River mouth. On BC Highway 99, the locality is by road about 100 kilometres (62 mi) northeast of Pemberton, 64 kilometres (40 mi) northwest of Lytton, and 172 kilometres (107 mi) west of Kamloops.

Prince Rupert is a port city in the province of British Columbia, Canada. Its location is on Kaien Island near the Alaskan panhandle. It is the land, air, and water transportation hub of British Columbia's North Coast, and has a population of 12,220 people as of 2016.

Ladysmith, originally Oyster Harbour, is a town located on the 49th parallel north on the east coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. The local economy is based on forestry, tourism, and agriculture. A hillside location adjacent to a sheltered harbour forms the natural geography of the community.

Terrace is a city in the Skeena region of west central British Columbia, Canada. This regional hub lies east of the confluence of the Kitsumkalum River into the Skeena River. On BC Highway 16, junctions branch northward for the Nisga'a Highway to the west and southward for the Stewart–Cassiar Highway to the east. The locality is by road about 204 kilometres (127 mi) southwest of Smithers and 144 kilometres (89 mi) east of Prince Rupert. Transportation links are the Northwest Regional Airport, a passenger train, and bus services.

Merritt is a city in the Nicola Valley of the south-central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It is 270 km (170 mi) northeast of Vancouver. Situated at the confluence of the Nicola and Coldwater rivers, it is the first major community encountered after travelling along Phase One of the Coquihalla Highway and acts as the gateway to all other major highways to the B.C. Interior. The city developed in 1893 when part of the ranches owned by William Voght, Jesus Garcia, and John Charters were surveyed for a town site.

The Regional District of Bulkley–Nechako (RDBN) is a regional district in the Canadian province of British Columbia, Canada. As of the 2021 census, the population was 37,737. The area is 73,419.01 square kilometres. The regional district offices are in Burns Lake.

The Cowichan Valley Regional District is a regional district in the Canadian province of British Columbia that is on the southern part of Vancouver Island, bordered by the Nanaimo and Alberni-Clayoquot Regional Districts to the north and northwest, and by the Capital Regional District to the south and east. As of the 2021 Census, the Regional District had a population of 89,013. The regional district offices are in Duncan.

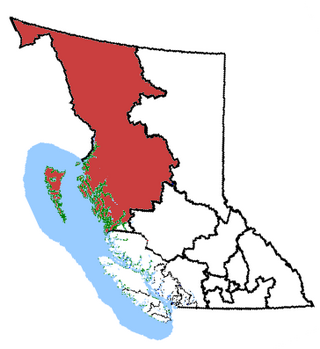

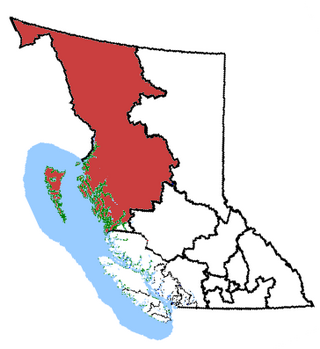

Cariboo—Prince George is a federal electoral district in the province of British Columbia, Canada, that has been represented in the House of Commons of Canada since 2004.

Prince George—Peace River—Northern Rockies is a federal electoral district in northern British Columbia, Canada. It has been represented in the House of Commons of Canada since 1968.

Skeena—Bulkley Valley is a federal electoral district in British Columbia, Canada, that has been represented in the House of Commons of Canada since 2004.

Telkwa is a village located along British Columbia Highway 16, nearly 15 kilometres (9 mi) southeast of the town of Smithers and 350 kilometres (220 mi) west of the city of Prince George, in northwest British Columbia, Canada.

Kitimat is a district municipality in the North Coast region of British Columbia, Canada. It is a member municipality of the Regional District of Kitimat–Stikine regional government. The Kitimat Valley is part of the most populous urban district in northwest British Columbia, which includes Terrace to the north along the Skeena River Valley. The city was planned and built by the Aluminum Company of Canada (Alcan) during the 1950s. Its post office was approved on 6 June 1952.

Port Hardy is a district municipality in British Columbia, Canada located on the north-east tip of Vancouver Island. Port Hardy has a population of 3,902 as of the 2021 census.

Houston is a forestry, mining and tourism town in the Bulkley Valley of the Northern Interior of British Columbia, Canada. Its population as of 2021 was 3,052, with approximately 2,000 in the surrounding rural area. It is known as the "steelhead capital" and it has the world's largest fly fishing rod. Houston's tourism industry is largely based on ecotourism and Steelhead Park, situated along Highway 16. Houston is named in honour of the pioneer newspaperman John Houston.

The Regional District of Fraser–Fort George (RDFFG) is a regional district located in the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It is bounded by the Alberta border to the east, the Columbia–Shuswap and Thompson–Nicola regional districts to the south and southeast, Cariboo Regional District to the southwest, the Regional District of Bulkley–Nechako to the west, and the Peace River Regional District to the north and northeast. As of the Canada 2011 Census, Fraser–Fort George had a population of 91,879 and a land area of 51,083.73 km2. The offices of the regional district are located at Prince George.

The Bulkley Valley is in the northwest Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada.

New Hazelton is a district municipality on the south side of the Bulkley River in the Skeena region of west central British Columbia, Canada. On BC Highway 16, the locality is by road about 68 kilometres (42 mi) northwest of Smithers and 137 kilometres (85 mi) northeast of Terrace. New Hazelton is one of the "Three Hazeltons", the other two being the original "Old" Hazelton to the northwest and South Hazelton to the west.

The Jasper–Prince Rupert train is a Canadian passenger train service operated by Via Rail between Jasper, Alberta, Prince George and Prince Rupert in British Columbia.

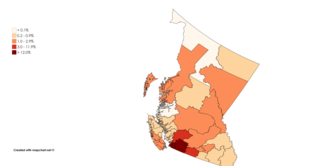

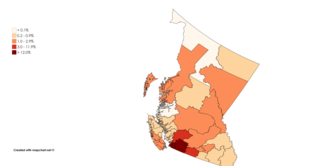

The South Asian community in British Columbia was first established in 1897. The first immigrants originated from Punjab, British India, a northern region and state in modern-day India and Pakistan. Punjabis originally settled in rural British Columbia at the turn of the twentieth century, working in the forestry and agricultural industries.

South Hazelton is an unincorporated community in the Skeena region of west central British Columbia, Canada. The place is on the east side of the Skeena River immediately south of the Bulkley River mouth. On BC Highway 16, the locality is by road about 73 kilometres (45 mi) northwest of Smithers and 132 kilometres (82 mi) northeast of Terrace. South Hazelton is one of the "Three Hazeltons", the other two being the original "Old" Hazelton to the north and New Hazelton to the east.