In Nordic mythology, Asgard is a location associated with the gods. It appears in several Old Norse sagas and mythological texts, including the Eddas, however it has also been suggested to be referred to indirectly in some of these sources. It is described as the fortified home of the Æsir gods and is often associated with gold imagery and contains many other locations known in Nordic mythology such as Valhöll, Iðavöllr and Hlidskjálf.

In Norse cosmology, Álfheimr, also called "Ljósálfheimr", is home of the Light Elves.

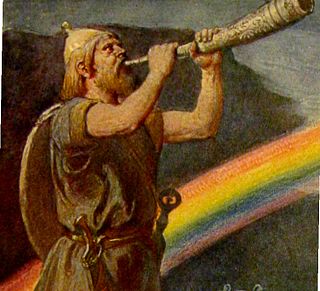

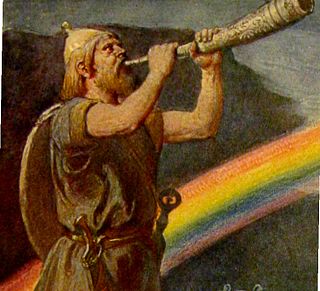

In Norse mythology, Bifröst, also called Bilröst, is a burning rainbow bridge that reaches between Midgard (Earth) and Asgard, the realm of the gods. The bridge is attested as Bilröst in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; as Bifröst in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; and in the poetry of skalds. Both the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda alternately refer to the bridge as Ásbrú.

Breiðablik is the home of Baldr in Nordic mythology.

Grímnismál is one of the mythological poems of the Poetic Edda. It is preserved in the Codex Regius manuscript and the AM 748 I 4to fragment. It is spoken through the voice of Grímnir, one of the many guises of the god Odin. The very name suggests guise, or mask or hood. Through an error, King Geirröth tortured Odin-as-Grímnir, a fatal mistake, since Odin caused him to fall upon his own sword. The poem is written mostly in the ljóðaháttr metre, typical for wisdom verse.

In Norse mythology, Huginn and Muninn are a pair of ravens that fly all over the world, Midgard, and bring information to the god Odin. Huginn and Muninn are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources: the Prose Edda and Heimskringla; in the Third Grammatical Treatise, compiled in the 13th century by Óláfr Þórðarson; and in the poetry of skalds. The names of the ravens are sometimes anglicized as Hugin and Munin, the same spelling as used in modern Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish.

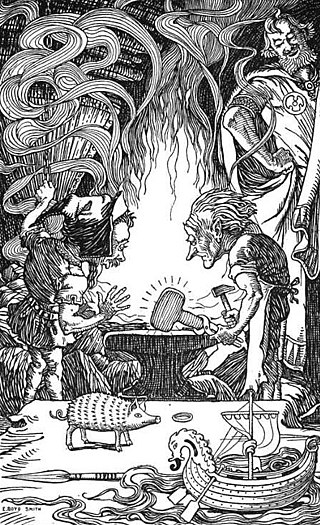

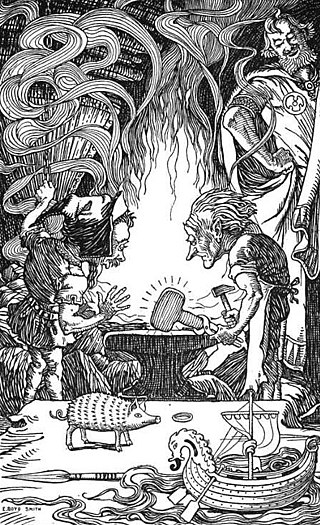

Skíðblaðnir, sometimes anglicized as Skidbladnir or Skithblathnir, is the best of ships in Norse mythology. It is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, both written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. All sources note that the ship is the finest of ships, and the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda attest that it is owned by the god Freyr, while the euhemerized account in Heimskringla attributes it to the magic of Odin. Both Heimskringla and the Prose Edda attribute to it the ability to be folded up—as cloth may be—into one's pocket when not needed.

The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems in alliterative verse. It is distinct from the closely related Prose Edda, although both works are seminal to the study of Old Norse poetry. Several versions of the Poetic Edda exist: especially notable is the medieval Icelandic manuscript Codex Regius, which contains 31 poems.

In Norse mythology, a valkyrie is one of a host of female figures who guide souls of the dead to the god Odin's hall Valhalla. There, the deceased warriors become einherjar. When the einherjar are not preparing for the cataclysmic events of Ragnarök, the valkyries bear them mead. Valkyries also appear as lovers of heroes and other mortals, where they are sometimes described as the daughters of royalty, sometimes accompanied by ravens and sometimes connected to swans or horses.

In Norse mythology, Sæhrímnir is the creature killed and eaten every night by the Æsir and einherjar. The cook of the gods, Andhrímnir, is responsible for the slaughter of Sæhrímnir and its preparation in the cauldron Eldhrímnir. After Sæhrímnir is eaten, the beast is brought back to life again to provide sustenance for the following day. Sæhrímnir is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional material, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

In Norse mythology, Ýdalir ("yew-dales") is a location containing a dwelling owned by the god Ullr. Ýdalir is solely attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources. Scholarly theories have been proposed about the implications of the location.

Máni is the Moon personified in Germanic mythology. Máni, personified, is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Both sources state that he is the brother of the personified sun, Sól, and the son of Mundilfari, while the Prose Edda adds that he is followed by the children Hjúki and Bil through the heavens. As a proper noun, Máni appears throughout Old Norse literature. Scholars have proposed theories about Máni's potential connection to the Northern European notion of the Man in the Moon, and a potentially otherwise unattested story regarding Máni through skaldic kennings.

Sól or Sunna is the Sun personified in Germanic mythology. One of the two Old High German Merseburg Incantations, written in the 9th or 10th century CE, attests that Sunna is the sister of Sinthgunt. In Norse mythology, Sól is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

In Norse mythology, four stags or harts eat among the branches of the world tree Yggdrasill. According to the Poetic Edda, the stags crane their necks upward to chomp at the branches. The morning dew gathers in their horns and forms the rivers of the world. Their names are given as Dáinn, Dvalinn, Duneyrr and Duraþrór. An amount of speculation exists regarding the deer and their potential symbolic value.

Sigrdrífumál is the conventional title given to a section of the Poetic Edda text in Codex Regius.

Glaðr is a horse in Nordic mythology. It is listed as among the horses of the Æsir ridden to Yggdrasil each morning in the Poetic Edda. The Prose Edda specifically refers to it as one of the horses of the Day, along with Skinfaxi.

In Norse mythology, Sága is a goddess associated with the location Sökkvabekkr. At Sökkvabekkr, Sága and the god Odin merrily drink as cool waves flow. Both Sága and Sökkvabekkr are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Scholars have proposed theories about the implications of the goddess and her associated location, including that the location may be connected to the goddess Frigg's fen residence Fensalir and that Sága may be another name for Frigg.

In Norse mythology, the Æsir–Vanir War was a conflict between two groups of deities that ultimately resulted in the unification of the Æsir and the Vanir into a single pantheon. The war is an important event in Norse mythology, and the implications for the potential historicity surrounding accounts of the war are a matter of scholarly debate and discourse.

In Norse mythology, the Kerlaugar i.e. "bath-tub", are two rivers through which the god Thor wades. The Kerlaugar are attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional material, and in a citation of the same verse in the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

These are family trees of the Norse gods showing kin relations among gods and other beings in Nordic mythology. Each family tree gives an example of relations according to principally Eddic material however precise links vary between sources. In addition, some beings are identified by some sources and scholars.