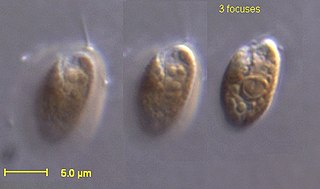

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all forms of life. Every cell consists of cytoplasm enclosed within a membrane; many cells contain organelles, each with a specific function. The term comes from the Latin word cellula meaning 'small room'. Most cells are only visible under a microscope. Cells emerged on Earth about 4 billion years ago. All cells are capable of replication, protein synthesis, and motility.

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells.

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name organelle comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence organelle, the suffix -elle being a diminutive. Organelles are either separately enclosed within their own lipid bilayers or are spatially distinct functional units without a surrounding lipid bilayer. Although most organelles are functional units within cells, some function units that extend outside of cells are often termed organelles, such as cilia, the flagellum and archaellum, and the trichocyst.

In biology, a kingdom is the second highest taxonomic rank, just below domain. Kingdoms are divided into smaller groups called phyla.

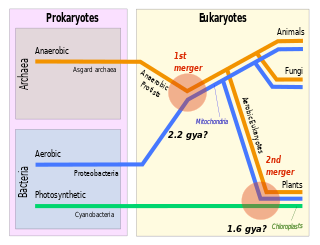

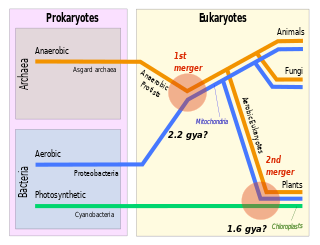

Symbiogenesis is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possibly other organelles of eukaryotic cells are descended from formerly free-living prokaryotes taken one inside the other in endosymbiosis. Mitochondria appear to be phylogenetically related to Rickettsiales bacteria, while chloroplasts are thought to be related to cyanobacteria.

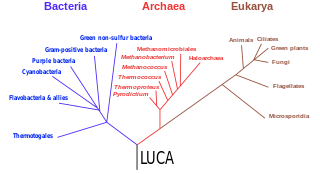

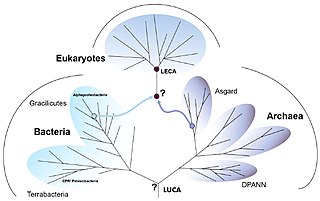

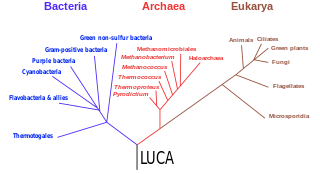

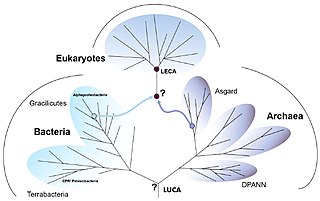

In biological taxonomy, a domain, also dominion, superkingdom, realm, or empire, is the highest taxonomic rank of all organisms taken together. It was introduced in the three-domain system of taxonomy devised by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis in 1990.

The three-domain system is a taxonomic classification system that groups all cellular life into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya, introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis in 1990. The key difference from earlier classifications such as the two-empire system and the five-kingdom classification is the splitting of Archaea from Bacteria as completely different organisms. It has been challenged by the two-domain system that divides organisms into Bacteria and Archaea only, as Eukaryotes are considered as a clade of Archaea.

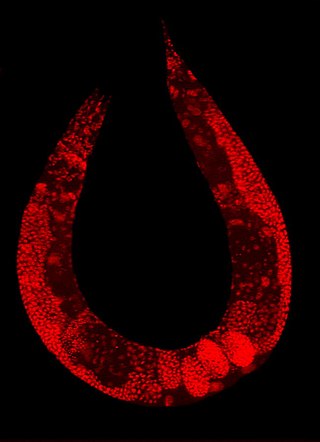

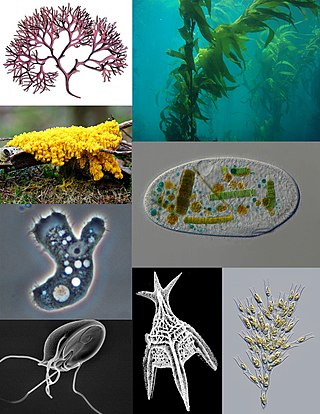

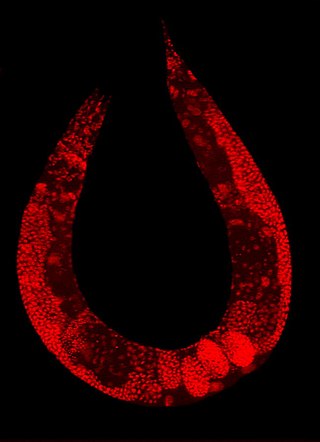

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism. All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and partially multicellular, like slime molds and social amoebae such as the genus Dictyostelium.

A prokaryote is a single-cell organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word prokaryote comes from the Ancient Greek πρό 'before' and κάρυον 'nut, kernel'. In the two-empire system arising from the work of Édouard Chatton, prokaryotes were classified within the empire Prokaryota. But in the three-domain system, based upon molecular analysis, prokaryotes are divided into two domains: Bacteria and Archaea. Organisms with nuclei are placed in a third domain, Eukaryota.

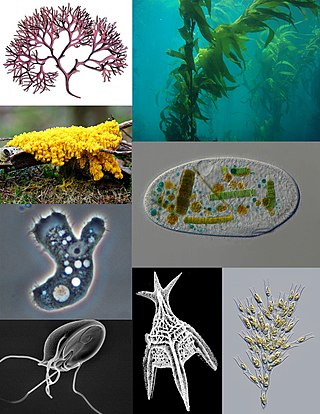

A protist or protoctist is any eukaryotic organism that is not an animal, land plant, or fungus. Protists do not form a natural group, or clade, but are a polyphyletic grouping of several independent clades that evolved from the last eukaryotic common ancestor.

Protozoa are a polyphyletic group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic debris. Historically, protozoans were regarded as "one-celled animals".

Archaea is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotic. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria, but this term has fallen out of use.

The eukaryotes constitute the domain of Eukarya or Eukaryota, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of life forms alongside the two groups of prokaryotes: the Bacteria and the Archaea. Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but given their generally much larger size, their collective global biomass is much larger than that of prokaryotes.

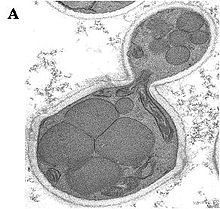

Fission, in biology, is the division of a single entity into two or more parts and the regeneration of those parts to separate entities resembling the original. The object experiencing fission is usually a cell, but the term may also refer to how organisms, bodies, populations, or species split into discrete parts. The fission may be binary fission, in which a single organism produces two parts, or multiple fission, in which a single entity produces multiple parts.

Marine microorganisms are defined by their habitat as microorganisms living in a marine environment, that is, in the saltwater of a sea or ocean or the brackish water of a coastal estuary. A microorganism is any microscopic living organism or virus, which is invisibly small to the unaided human eye without magnification. Microorganisms are very diverse. They can be single-celled or multicellular and include bacteria, archaea, viruses, and most protozoa, as well as some fungi, algae, and animals, such as rotifers and copepods. Many macroscopic animals and plants have microscopic juvenile stages. Some microbiologists also classify viruses as microorganisms, but others consider these as non-living.

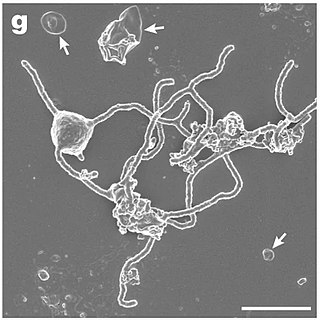

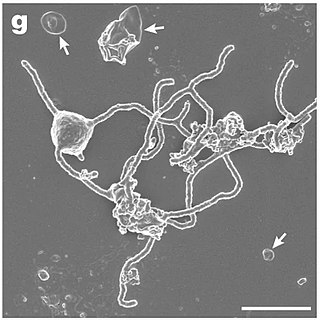

Lokiarchaeota is a proposed phylum of the Archaea. The phylum includes all members of the group previously named Deep Sea Archaeal Group, also known as Marine Benthic Group B. Lokiarchaeota is part of the superphylum Asgard containing the phyla: Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, Heimdallarchaeota, and Helarchaeota. A phylogenetic analysis disclosed a monophyletic grouping of the Lokiarchaeota with the eukaryotes. The analysis revealed several genes with cell membrane-related functions. The presence of such genes support the hypothesis of an archaeal host for the emergence of the eukaryotes; the eocyte-like scenarios.

The initial version of a classification system of life by British zoologist Thomas Cavalier-Smith appeared in 1978. This initial system continued to be modified in subsequent versions that were published until he died in 2021. As with classifications of others, such as Carl Linnaeus, Ernst Haeckel, Robert Whittaker, and Carl Woese, Cavalier-Smith's classification attempts to incorporate the latest developments in taxonomy., Cavalier-Smith used his classifications to convey his opinions about the evolutionary relationships among various organisms, principally microbial. His classifications complemented his ideas communicated in scientific publications, talks, and diagrams. Different iterations might have a wider or narrow scope, include different groupings, provide greater or lesser detail, and place groups in different arrangements as his thinking changed. His classifications has been a major influence in the modern taxonomy, particularly of protists.

Eukaryogenesis, the process which created the eukaryotic cell and lineage, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. The process is widely agreed to have involved symbiogenesis, in which archaea and bacteria came together to create the first eukaryotic common ancestor (FECA). This cell had a new level of complexity and capability, with a nucleus, at least one centriole and cilium, facultatively aerobic mitochondria, sex, a dormant cyst with a cell wall of chitin and/or cellulose and peroxisomes. It evolved into a population of single-celled organisms that included the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA), gaining capabilities along the way, though the sequence of the steps involved has been disputed, and may not have started with symbiogenesis. In turn, the LECA gave rise to the eukaryotes' crown group, containing the ancestors of animals, fungi, plants, and a diverse range of single-celled organisms.

Marine prokaryotes are marine bacteria and marine archaea. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryotes that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. All cellular life forms can be divided into prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Eukaryotes are organisms whose cells have a nucleus enclosed within membranes, whereas prokaryotes are the organisms that do not have a nucleus enclosed within a membrane. The three-domain system of classifying life adds another division: the prokaryotes are divided into two domains of life, the microscopic bacteria and the microscopic archaea, while everything else, the eukaryotes, become the third domain.

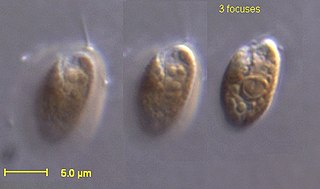

Marine protists are defined by their habitat as protists that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish water of coastal estuaries. Life originated as marine single-celled prokaryotes and later evolved into more complex eukaryotes. Eukaryotes are the more developed life forms known as plants, animals, fungi and protists. Protists are the eukaryotes that cannot be classified as plants, fungi or animals. They are mostly single-celled and microscopic. The term protist came into use historically as a term of convenience for eukaryotes that cannot be strictly classified as plants, animals or fungi. They are not a part of modern cladistics because they are paraphyletic.