Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other vertebrates. Human malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, fatigue, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. Symptoms usually begin 10 to 15 days after being bitten by an infected Anopheles mosquito. If not properly treated, people may have recurrences of the disease months later. In those who have recently survived an infection, reinfection usually causes milder symptoms. This partial resistance disappears over months to years if the person has no continuing exposure to malaria.

Plasmodium is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of Plasmodium species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a vertebrate host during a blood meal. Parasites grow within a vertebrate body tissue before entering the bloodstream to infect red blood cells. The ensuing destruction of host red blood cells can result in malaria. During this infection, some parasites are picked up by a blood-feeding insect, continuing the life cycle.

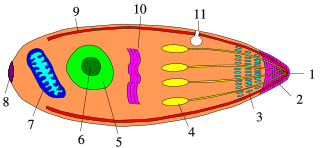

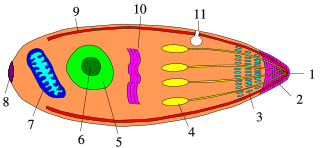

A trophozoite is the activated, feeding stage in the life cycle of certain protozoa such as malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum and those of the Giardia group. The complementary form of the trophozoite state is the thick-walled cyst form. They are often different from the cyst stage, which is a protective, dormant form of the protozoa. Trophozoites are often found in the host's body fluids and tissues and in many cases, they are the form of the protozoan that causes disease in the host. In the protozoan, Entamoeba histolytica it invades the intestinal mucosa of its host, causing dysentery, which aid in the trophozoites traveling to the liver and leading to the production of hepatic abscesses.

A gametocyte is a eukaryotic germ cell that divides by mitosis into other gametocytes or by meiosis into gametids during gametogenesis. Male gametocytes are called spermatocytes, and female gametocytes are called oocytes.

Plasmodium vivax is a protozoal parasite and a human pathogen. This parasite is the most frequent and widely distributed cause of recurring malaria. Although it is less virulent than Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest of the five human malaria parasites, P. vivax malaria infections can lead to severe disease and death, often due to splenomegaly. P. vivax is carried by the female Anopheles mosquito; the males do not bite.

Plasmodium ovale is a species of parasitic protozoon that causes tertian malaria in humans. It is one of several species of Plasmodium parasites that infect humans, including Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax which are responsible for most cases of malaria in the world. P. ovale is rare compared to these two parasites, and substantially less dangerous than P. falciparum.

Plasmodium malariae is a parasitic protozoan that causes malaria in humans. It is one of several species of Plasmodium parasites that infect other organisms as pathogens, also including Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, responsible for most malarial infection. Found worldwide, it causes a so-called "benign malaria", not nearly as dangerous as that produced by P. falciparum or P. vivax. The signs include fevers that recur at approximately three-day intervals – a quartan fever or quartan malaria – longer than the two-day (tertian) intervals of the other malarial parasite.

Merozoitesurface proteins are both integral and peripheral membrane proteins found on the surface of a merozoite, an early life cycle stage of a protozoan. Merozoite surface proteins, or MSPs, are important in understanding malaria, a disease caused by protozoans of the genus Plasmodium. During the asexual blood stage of its life cycle, the malaria parasite enters red blood cells to replicate itself, causing the classic symptoms of malaria. These surface protein complexes are involved in many interactions of the parasite with red blood cells and are therefore an important topic of study for scientists aiming to combat malaria.

Plasmodium knowlesi is a parasite that causes malaria in humans and other primates. It is found throughout Southeast Asia, and is the most common cause of human malaria in Malaysia. Like other Plasmodium species, P. knowlesi has a life cycle that requires infection of both a mosquito and a warm-blooded host. While the natural warm-blooded hosts of P. knowlesi are likely various Old World monkeys, humans can be infected by P. knowlesi if they are fed upon by infected mosquitoes. P. knowlesi is a eukaryote in the phylum Apicomplexa, genus Plasmodium, and subgenus Plasmodium. It is most closely related to the human parasite Plasmodium vivax as well as other Plasmodium species that infect non-human primates.

Malaria culture is a method for growing malaria parasites outside the body, i.e., in an ex vivo environment. Although attempts for propagation of the parasites outside of humans or animal models reach as far back as 1912, the success of the initial attempts was limited to one or just a few cycles. The first successful continuous culture was established in 1976. Initial hopes that the ex vivo culture would lead quickly to the discovery of a vaccine were premature. However, the development of new drugs was greatly facilitated.

Plasmodium eylesi is a parasite of the genus Plasmodium subgenus Plasmodium.

Malaria vaccines are vaccines that prevent malaria, a mosquito-borne infectious disease which annually affects an estimated 247 million people worldwide and causes 619,000 deaths. The first approved vaccine for malaria is RTS,S, known by the brand name Mosquirix. As of April 2023, the vaccine has been given to 1.5 million children living in areas with moderate-to-high malaria transmission. It requires at least three doses in infants by age 2, and a fourth dose extends the protection for another 1–2 years. The vaccine reduces hospital admissions from severe malaria by around 30%.

The history of malaria extends from its prehistoric origin as a zoonotic disease in the primates of Africa through to the 21st century. A widespread and potentially lethal human infectious disease, at its peak malaria infested every continent except Antarctica. Its prevention and treatment have been targeted in science and medicine for hundreds of years. Since the discovery of the Plasmodium parasites which cause it, research attention has focused on their biology as well as that of the mosquitoes which transmit the parasites.

Apicomplexans, a group of intracellular parasites, have life cycle stages that allow them to survive the wide variety of environments they are exposed to during their complex life cycle. Each stage in the life cycle of an apicomplexan organism is typified by a cellular variety with a distinct morphology and biochemistry.

Nycteria is a genus of protozoan parasites that belong to the phylum Apicomplexa. It is composed of vector-borne haemosporidian parasites that infect a wide range of mammals such as primates, rodents and bats. Its vertebrate hosts are bats. First described by Garnham and Heisch in 1953, Nycteria is mostly found in bat species where it feeds off the blood of their hosts and causes disease. Within the host, Nycteria develops into peculiar lobulated schizonts in parenchyma cells of the liver, similarly to the stages of Plasmodium falciparum in the liver. The vector of Nycteria has been hard to acquire and identify. Because of this, the life cycle of Nycteria still remains unknown and understudied. It has been suggested that this vector could be an arthropod other than a mosquito or the vector of most haemosporidian parasites.

Pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) or placental malaria is a presentation of the common illness that is particularly life-threatening to both mother and developing fetus. PAM is caused primarily by infection with Plasmodium falciparum, the most dangerous of the four species of malaria-causing parasites that infect humans. During pregnancy, a woman faces a much higher risk of contracting malaria and of associated complications. Prevention and treatment of malaria are essential components of prenatal care in areas where the parasite is endemic – tropical and subtropical geographic areas. Placental malaria has also been demonstrated to occur in animal models, including in rodent and non-human primate models.

Plasmodium coatneyi is a parasitic species that is an agent of malaria in nonhuman primates. P. coatneyi occurs in Southeast Asia. The natural host of this species is the rhesus macaque and crab-eating macaque, but there has been no evidence that zoonosis of P. coatneyi can occur through its vector, the female Anopheles mosquito.

Plasmodium cynomolgi is an apicomplexan parasite that infects mosquitoes and Asian Old World monkeys. In recent years, a number of natural infections of humans have also been documented. This species has been used as a model for human Plasmodium vivax because Plasmodium cynomolgi shares the same life cycle and some important biological features with P. vivax.

Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) is a family of proteins present on the membrane surface of red blood cells that are infected by the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum. PfEMP1 is synthesized during the parasite's blood stage inside the RBC, during which the clinical symptoms of falciparum malaria are manifested. Acting as both an antigen and adhesion protein, it is thought to play a key role in the high level of virulence associated with P. falciparum. It was discovered in 1984 when it was reported that infected RBCs had unusually large-sized cell membrane proteins, and these proteins had antibody-binding (antigenic) properties. An elusive protein, its chemical structure and molecular properties were revealed only after a decade, in 1995. It is now established that there is not one but a large family of PfEMP1 proteins, genetically regulated (encoded) by a group of about 60 genes called var. Each P. falciparum is able to switch on and off specific var genes to produce a functionally different protein, thereby evading the host's immune system. RBCs carrying PfEMP1 on their surface stick to endothelial cells, which facilitates further binding with uninfected RBCs, ultimately helping the parasite to both spread to other RBCs as well as bringing about the fatal symptoms of P. falciparum malaria.

Quartan fever is one of the four types of malaria which can be contracted by humans.