McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819), was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that defined the scope of the U.S. Congress's legislative power and how it relates to the powers of American state legislatures. The dispute in McCulloch involved the legality of the national bank and a tax that the state of Maryland imposed on it. In its ruling, the Supreme Court established firstly that the "Necessary and Proper" Clause of the U.S. Constitution gives the U.S. federal government certain implied powers necessary and proper for the exercise of the powers enumerated explicitly in the Constitution, and secondly that the American federal government is supreme over the states, and so states' ability to interfere with the federal government is restricted. Since the legislature has the authority to tax and spend, the court held that it therefore has authority to establish a national bank, as being "necessary and proper" to that end.

Sodomy laws in the United States, which outlawed a variety of sexual acts, were inherited from colonial laws in the 17th century. While they often targeted sexual acts between persons of the same sex, many statutes employed definitions broad enough to outlaw certain sexual acts between persons of different sexes, in some cases even including acts between married persons.

The Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause, is a clause in Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution:

The Congress shall have Power... To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.

Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003), was a court case in the United States which questioned the constitutionality of the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act's retroactive requirements. Under the Act, any sex offender must register with the Department of Corrections or local law enforcement within one business day of entering the state. This information is forwarded to the Department of Public Safety, which maintains a public database. Fingerprints, social security number, anticipated change of address, and medical treatment after the offense are kept confidential. The offender's name, aliases, address, photograph, physical description, driver's license number, motor vehicle identification numbers, place of employment, date of birth, crime, date and place of conviction, and length and conditions of sentence are part of the public record, maintained on the Internet.

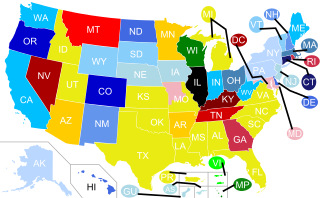

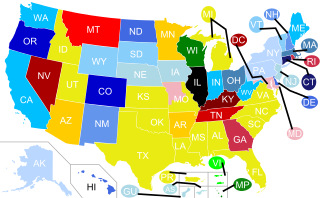

Some jurisdictions may commit certain types of dangerous sex offenders to state-run detention facilities following the completion of their sentence if that person has a "mental abnormality" or personality disorder that makes the person likely to engage in sexual offenses if not confined in a secure facility. In the United States, twenty states, the federal government, and the District of Columbia have a version of these commitment laws, which are referred to as "Sexually Violent Predator" (SVP) or "Sexually Dangerous Persons" laws.

The enumerated powers of the United States Congress are the powers granted to the federal government of the United States by the United States Constitution. Most of these powers are listed in Article I, Section 8.

The Dru Sjodin National Sex Offender Public Registry is a cooperative effort between U.S. state agencies that host public sex offender registries and the U.S. federal government. The registry is coordinated by the United States Department of Justice and operates a web site search tool allowing a user to submit a single query to obtain information about sex offenders throughout the United States.

Jessica's Law is the informal name given to a 2005 Florida law, as well as laws in several other states, designed to protect potential victims and reduce a sexual offender's ability to re-offend. A version of Jessica's Law, known as the Jessica Lunsford Act, was introduced at the federal level in 2005 but was never enacted into law by Congress.

Sandra Lea Lynch is an American lawyer who serves as a senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. She is the first woman to serve on that court. Lynch served as chief judge of the First Circuit from 2008 to 2015.

The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act is a federal statute that was signed into law by U.S. President George W. Bush on July 27, 2006. The Walsh Act organizes sex offenders into three tiers according to the crime committed, and mandates that Tier 3 offenders update their whereabouts every three months with lifetime registration requirements. Tier 2 offenders must update their whereabouts every six months with 25 years of registration, and Tier 1 offenders must update their whereabouts every year with 15 years of registration. Failure to register and update information is a felony under the law. States are required to publicly disclose information of Tier 2 and Tier 3 offenders, at minimum. It also contains civil commitment provisions for sexually dangerous people.

Kansas v. Crane, 534 U.S. 407 (2002), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the Kansas Sexually Violent Predator Act (SVPA) as consistent with substantive due process. The Court clarified that its earlier holding in Kansas v. Hendricks (1997) did not set forth a requirement of total or complete lack of control, but it noted that the US Constitution does not permit commitment of a sex offender without some lack-of-control determination.

Medellín v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491 (2008), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court that held even when a treaty constitutes an international commitment, it is not binding domestic law unless it has been implemented by an act of the U.S. Congress or contains language expressing that it is "self-executing" upon ratification. The Court also ruled that decisions of the International Court of Justice are not binding upon the U.S. and, like treaties, cannot be enforced by the president without authority from Congress or the U.S. Constitution.

Chamber of Commerce v. Whiting, 563 U.S. 582 (2011), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that upheld an Arizona state law suspending or revoking business licenses of businesses that hire illegal aliens.

Leal Garcia v. Texas, 564 U.S. 940 (2011), was a ruling in which the Supreme Court of the United States denied Humberto Leal García's application for stay of execution and application for writ of habeas corpus. Leal was subsequently executed by lethal injection. The central issue was not Leal's guilt, but rather that he was not notified of his right to call his consulate as required by international law. The Court did not stay the execution because Congress had never enacted legislation regarding this provision of international law. The ruling attracted a great deal of commentary and Leal's case was supported by attorneys specializing in international law and several former United States diplomats.

United States v. Alfonso D. Lopez, Jr., 514 U.S. 549 (1995), was a landmark case of the United States Supreme Court that struck down the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 (GFSZA) due to it being outside of Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. It was the first case since 1937 in which the Court held that Congress had exceeded its power under the Commerce Clause.

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012), is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in which the Court upheld Congress's power to enact most provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), commonly called Obamacare, and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act (HCERA), including a requirement for most Americans to pay a penalty for forgoing health insurance by 2014. The Acts represented a major set of changes to the American health care system that had been the subject of highly contentious debate, largely divided on political party lines.

United States obscenity law deals with the regulation or suppression of what is considered obscenity and therefore not protected speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. In the United States, discussion of obscenity typically relates to defining what pornography is obscene, as well as to issues of freedom of speech and of the press, otherwise protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Issues of obscenity arise at federal and state levels. State laws operate only within the jurisdiction of each state, and there are differences among such laws. Federal statutes ban obscenity and child pornography produced with real children. Federal law also bans broadcasting of "indecent" material during specified hours.

United States v. Kebodeaux, 570 U.S. 387 (2013), was a recent case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Sex Offender Notification and Registration Act (SORNA) was constitutional under the Necessary and Proper Clause.

The constitutionality of sex offender registries in the United States has been challenged on a number of grounds, generating a substantial amount of case law. The Supreme Court of the United States has twice examined sex offender registration laws and upheld them both times. Those challenging the sex offender registration and related restriction statutes have claimed violations of the ex post facto, due process, cruel and unusual punishment, equal protection and search and seizure provisions of the United States Constitution. A study published in fall 2015 found that statistics cited in two U.S. Supreme Court decisions that are often cited in decisions upholding the constitutionality of sex offender policies are unfounded. Several challenges to some parts of state level sex offender laws have been honored after hearing at the state level.

Gundy v. United States, No. 17-6086, 588 U.S. ___ (2019), was a United States Supreme Court case that held that 42 U.S.C. § 16913(d), part of the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act ("SORNA"), does not violate the nondelegation doctrine. The section of the SORNA allows the Attorney General to "specify the applicability" of the mandatory registration requirements of "sex offenders convicted before the enactment of [SORNA]". Precedent is that it is only constitutional for Congress to delegate legislative power to the executive branch if it provides an "intelligible principle" as guidance. The outcome of the case could have greatly influenced the broad delegations of power Congress has made to the federal executive branch, but it did not.