Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the Constitution prohibits segregated public schools in the District of Columbia. Originally argued on December 10–11, 1952, a year before Brown v. Board of Education, Bolling was reargued on December 8–9, 1953, and was unanimously decided on May 17, 1954, the same day as Brown. The Bolling decision was supplemented in 1955 with the second Brown opinion, which ordered desegregation "with all deliberate speed". In Bolling, the Court did not address school desegregation in the context of the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, which applies only to the states, but rather held that school segregation was unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court observed that the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution lacked an Equal Protection Clause, as in the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court held, however, that the concepts of equal protection and due process are not mutually exclusive, establishing the reverse incorporation doctrine.

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court. The case overturned a judgment convicting an African American law student for trespassing by being in a restaurant in a bus terminal which was "whites only". It held that racial segregation in public transportation was illegal because such segregation violated the Interstate Commerce Act, which broadly forbade discrimination in interstate passenger transportation. It moreover held that bus transportation was sufficiently related to interstate commerce to allow the United States federal government to regulate it to forbid racial discrimination in the industry.

Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184 (1964), was a United States Supreme Court decision handed down in 1964 involving whether the state of Ohio could, consistent with the First Amendment, ban the showing of the Louis Malle film The Lovers, which the state had deemed obscene.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is a leading United States civil rights organization and law firm based in New York City.

Rogers v. Tennessee, 532 U.S. 451 (2001), was a U.S. Supreme Court case holding that there is no due process violation for lack of fair warning when pre-existing common law limitations on what acts constitute a crime, under a more broadly worded statutory criminal law, are broadened to include additional acts, even when there is no notice to the defendant that the court might undo the common law limitations, so long as the statutory criminal law was made prior to the acts, and so long as the expansion to the newly included acts is expected or defensible in reference to the statutory law. The court wrote,

In the context of common law doctrines... Strict application of ex post facto principles... would unduly impair the incremental and reasoned development of precedent that is the foundation of the common law system." The decision did not affect the requirement of fair warning placed on statutes passed by legislatures - "The Constitution's Ex Post Facto Clause... 'is a limitation upon the powers of the Legislature, and does not of its own force apply to the Judicial Branch of government'... a judicial alteration of a common law doctrine of criminal law [only] violates the principal of fair warning... where it is 'unexpected and indefensible by reference to the law which had been expressed prior to the conduct in issue.

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347 (1964), was a case in which the US Supreme Court held that due process prohibits retroactive application of any judicial construction of a criminal statute that is unexpected and indefensible by reference to the law that has been expressed prior to the conduct in issue. The holding is based on the Fourteenth Amendment prohibition by the Due Process Clause of ex post facto laws.

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964), was a United States Supreme Court case holding that criminal suspects have a right to counsel during police interrogations under the Sixth Amendment. The case was decided a year after the court had held in Gideon v. Wainwright that indigent criminal defendants have a right to be provided counsel at trial.

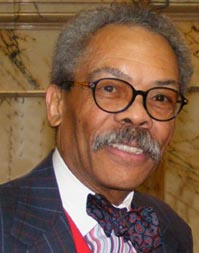

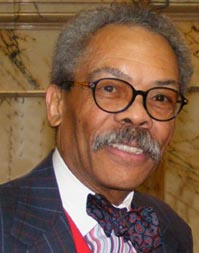

Robert Mack Bell is an American lawyer and jurist from Baltimore, Maryland. From 1996 to 2013, he served as Chief Judge on the Maryland Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state. He was the first African American to hold the position.

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965), is a United States Supreme Court case based on the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It held that a state government cannot employ "breach of the peace" statutes against protesters engaging in peaceable demonstrations that may potentially incite violence.

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 (1963), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court ruling that the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution forbade state government officials to force a crowd to disperse when they are otherwise legally marching in front of a state house.

Adderley v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966), was a United States Supreme Court case regarding whether arrests for protesting in front of a jail were constitutional.

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964), provided an opportunity for the Supreme Court of the United States to determine whether racial discrimination in the provision of public accommodations by a privately owned restaurant violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. However, due to a supervening change in the state law, the Court vacated the judgment of the Maryland Court of Appeals and remanded the case to allow that court to determine whether the convictions for criminal trespass of twelve African American students should be dismissed.

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States reversed the convictions of several white and African American persons who were refused service at a restaurant based upon a prior Court decision, holding that a Florida regulation requiring a restaurant that employed or served persons of both races to have separate lavatory rooms resulted in the state becoming entangled in racial discriminatory activity in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130 (1964), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States reversed the convictions of five African Americans who were arrested during a protest of a privately owned amusement park by a park employee who was also a deputy sheriff. The Court found that the convictions violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Aguilar v. Texas, 378 U.S. 108 (1964), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court, which held that “[a]lthough an affidavit supporting a search warrant may be based on hearsay information and need not reflect the direct personal observations of the affiant, the magistrate must be informed of some of the underlying circumstances relied on by the person providing the information and some of the underlying circumstances from which the affiant concluded that the informant, whose identity was not disclosed, was credible or his information reliable.” Along with Spinelli v. United States (1969), Aguilar established the Aguilar–Spinelli test, a judicial guideline for evaluating the validity of a search warrant based on information provided by a confidential informant or an anonymous tip. The test developed in this case was subsequently rejected and replaced in Illinois v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213 (1983).

Quantity of Books v. Kansas, 378 U.S. 205 (1973), is an in rem United States Supreme Court decision on First Amendment questions relating to the forfeiture of obscene material. By a 7–2 margin, the Court held that a seizure of the books was unconstitutional, since no hearing had been held on whether the books were obscene, and it reversed a Kansas Supreme Court decision that upheld the seizure.

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961), was a landmark case argued by Thurgood Marshall before the US Supreme Court. On December 11, 1961, the court unanimously ruled that Louisiana could not convict peaceful sit-in protesters who refused to leave dining establishments under the state's "disturbing the peace" laws.

This is a timeline of the 1947 to 1968 civil rights movement in the United States, a nonviolent mid-20th century freedom movement to gain legal equality and the enforcement of constitutional rights for People of Color. The goals of the movement included securing equal protection under the law, ending legally established racial discrimination, and gaining equal access to public facilities, education reform, fair housing, and the ability to vote.

Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court involving the application of the Speedy Trial Clause of the United States Constitution in state court proceedings. The Sixth Amendment in the Bill of Rights states that in criminal prosecutions "...the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy trial" In this case, a defendant was tried for trespassing and the initial jury could not reach a verdict. The prosecutor neither dismissed nor reinstated the case but used an unusual procedure to leave it open, potentially indefinitely. Klopfer argued that this denied him his right to a speedy trial. In deciding in his favor, the Supreme Court incorporated the speedy trial protections of the Sixth Amendment against the states.

Prior to the civil rights movement in South Carolina, African Americans in the state had very few political rights. South Carolina briefly had a majority-black government during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, but with the 1876 inauguration of Governor Wade Hampton III, a Democrat who supported the disenfranchisement of blacks, African Americans in South Carolina struggled to exercise their rights. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation kept African Americans from voting, and it was virtually impossible for someone to challenge the Democratic Party, which ran unopposed in most state elections for decades. By 1940, the voter registration provisions written into the 1895 constitution effectively limited African-American voters to 3,000—only 0.8 percent of those of voting age in the state.