Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is an infection of the vagina caused by excessive growth of bacteria. Common symptoms include increased vaginal discharge that often smells like fish. The discharge is usually white or gray in color. Burning with urination may occur. Itching is uncommon. Occasionally, there may be no symptoms. Having BV approximately doubles the risk of infection by a number of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS. It also increases the risk of early delivery among pregnant women.

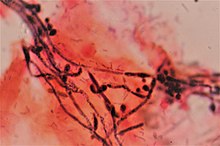

Candidiasis is a fungal infection due to any species of the genus Candida. When it affects the mouth, in some countries it is commonly called thrush. Signs and symptoms include white patches on the tongue or other areas of the mouth and throat. Other symptoms may include soreness and problems swallowing. When it affects the vagina, it may be referred to as a yeast infection or thrush. Signs and symptoms include genital itching, burning, and sometimes a white "cottage cheese-like" discharge from the vagina. Yeast infections of the penis are less common and typically present with an itchy rash. Very rarely, yeast infections may become invasive, spreading to other parts of the body. This may result in fevers, among other symptoms.

Vaginitis, also known as vulvovaginitis, is inflammation of the vagina and vulva. Symptoms may include itching, burning, pain, discharge, and a bad smell. Certain types of vaginitis may result in complications during pregnancy.

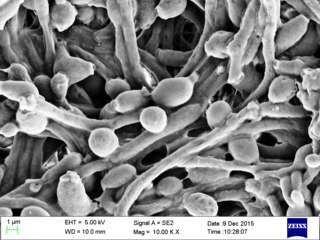

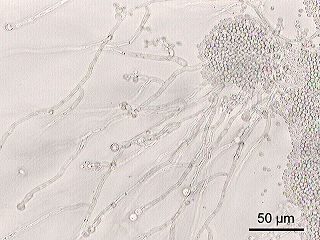

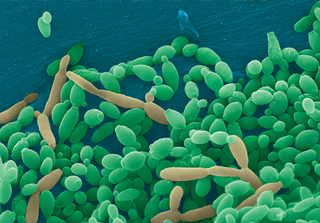

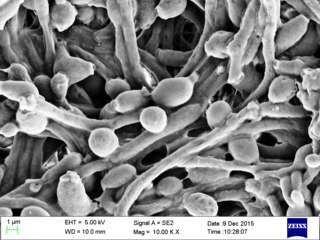

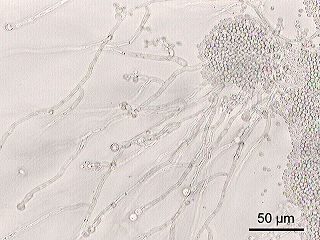

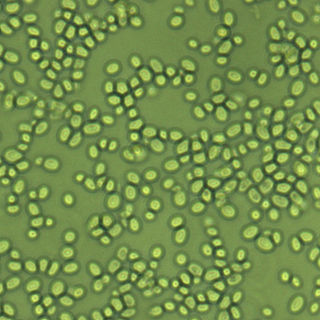

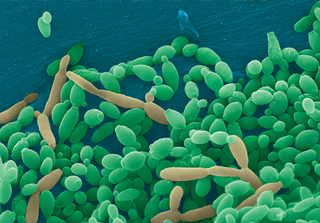

Candida albicans is an opportunistic pathogenic yeast that is a common member of the human gut flora. It can also survive outside the human body. It is detected in the gastrointestinal tract and mouth in 40–60% of healthy adults. It is usually a commensal organism, but it can become pathogenic in immunocompromised individuals under a variety of conditions. It is one of the few species of the genus Candida that cause the human infection candidiasis, which results from an overgrowth of the fungus. Candidiasis is, for example, often observed in HIV-infected patients. C. albicans is the most common fungal species isolated from biofilms either formed on (permanent) implanted medical devices or on human tissue. C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. glabrata are together responsible for 50–90% of all cases of candidiasis in humans. A mortality rate of 40% has been reported for patients with systemic candidiasis due to C. albicans. By one estimate, invasive candidiasis contracted in a hospital causes 2,800 to 11,200 deaths yearly in the US. Nevertheless, these numbers may not truly reflect the true extent of damage this organism causes, given new studies indicating that C. albicans can cross the blood–brain barrier in mice.

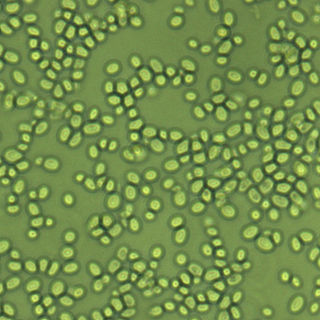

Candida is a genus of yeasts. It is the most common cause of fungal infections worldwide and the largest genus of medically important yeast.

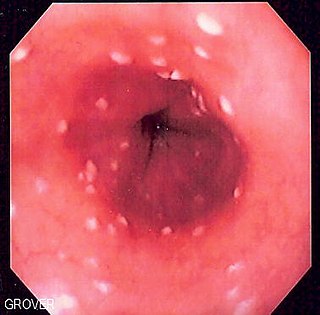

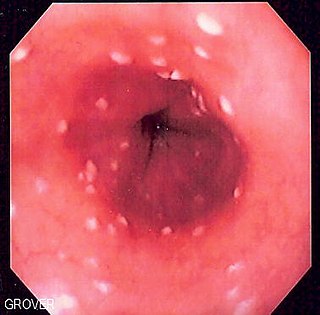

Oral candidiasis (Acute pseudomembranous candidiasis), also known as oral thrush among other names, is candidiasis that occurs in the mouth. That is, oral candidiasis is a mycosis (yeast/fungal infection) of Candida species on the mucous membranes of the mouth.

Fungal infection, also known as mycosis, is a disease caused by fungi. Different types are traditionally divided according to the part of the body affected; superficial, subcutaneous, and systemic. Superficial fungal infections include common tinea of the skin, such as tinea of the body, groin, hands, feet and beard, and yeast infections such as pityriasis versicolor. Subcutaneous types include eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis, which generally affect tissues in and beneath the skin. Systemic fungal infections are more serious and include cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis pneumonia, aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Signs and symptoms range widely. There is usually a rash with superficial infection. Fungal infection within the skin or under the skin may present with a lump and skin changes. Pneumonia-like symptoms or meningitis may occur with a deeper or systemic infection.

Terconazole is an antifungal drug used to treat vaginal yeast infection. It comes as a lotion or a suppository and disrupts the biosynthesis of fats in a yeast cell. It has a relatively broad spectrum compared to azole compounds but not triazole compounds. Testing shows that it is a suitable compound for prophylaxis for those that suffer from chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis.

Fungemia is the presence of fungi or yeast in the blood. The most common type, also known as candidemia, candedemia, or systemic candidiasis, is caused by Candida species. Candidemia is also among the most common bloodstream infections of any kind. Infections by other fungi, including Saccharomyces, Aspergillus and Cryptococcus, are also called fungemia. It is most commonly seen in immunosuppressed or immunocompromised patients with severe neutropenia, cancer patients, or in patients with intravenous catheters. It has been suggested that otherwise immunocompetent patients taking infliximab may also be at a higher risk.

Vaginal discharge is a mixture of liquid, cells, and bacteria that lubricate and protect the vagina. This mixture is constantly produced by the cells of the vagina and cervix, and it exits the body through the vaginal opening. The composition, amount, and quality of discharge varies between individuals and can vary throughout the menstrual cycle and throughout the stages of sexual and reproductive development. Normal vaginal discharge may have a thin, watery consistency or a thick, sticky consistency, and it may be clear or white in color. Normal vaginal discharge may be large in volume but typically does not have a strong odor, nor is it typically associated with itching or pain. While most discharge is considered physiologic or represents normal functioning of the body, some changes in discharge can reflect infection or other pathological processes. Infections that may cause changes in vaginal discharge include vaginal yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, and sexually transmitted infections. The characteristics of abnormal vaginal discharge vary depending on the cause, but common features include a change in color, a foul odor, and associated symptoms such as itching, burning, pelvic pain, or pain during sexual intercourse.

Nakaseomyces glabratus is a species of haploid yeast of the genus Nakaseomyces, previously known as Candida glabrata. Despite the fact that no sexual life cycle has been documented for this species, N. glabratus strains of both mating types are commonly found. N. glabrata is generally a commensal of human mucosal tissues, but in today's era of wider human immunodeficiency from various causes, N. glabratus is often the second or third most common cause of candidiasis as an opportunistic pathogen. Infections caused by N. glabratus can affect the urogenital tract or even cause systemic infections by entrance of the fungal cells in the bloodstream (Candidemia), especially prevalent in immunocompromised patients.

Esophageal candidiasis is an opportunistic infection of the esophagus by Candida albicans. The disease usually occurs in patients in immunocompromised states, including post-chemotherapy and in AIDS. However, it can also occur in patients with no predisposing risk factors, and is more likely to be asymptomatic in those patients. It is also known as candidal esophagitis or monilial esophagitis.

Clotrimazole, sold under the brand name Lotrimin, among others, is an antifungal medication. It is used to treat vaginal yeast infections, oral thrush, diaper rash, tinea versicolor, and types of ringworm including athlete's foot and jock itch. It can be taken by mouth or applied as a cream to the skin or in the vagina.

The vaginal flora in pregnancy, or vaginal microbiota in pregnancy, is different from the vaginal flora before sexual maturity, during reproductive years, and after menopause. A description of the vaginal flora of pregnant women who are immunocompromised is not covered in this article. The composition of the vaginal flora significantly differs in pregnancy. Bacteria or viruses that are infectious most often have no symptoms.

Invasive candidiasis is an infection (candidiasis) that can be caused by various species of Candida yeast. Unlike Candida infections of the mouth and throat or vagina, invasive candidiasis is a serious, progressive, and potentially fatal infection that can affect the blood (fungemia), heart, brain, eyes, bones, and other parts of the body.

Candida tropicalis is a species of yeast in the genus Candida. It is a common pathogen in neutropenic hosts, in whom it may spread through the bloodstream to peripheral organs. For invasive disease, treatments include amphotericin B, echinocandins, or extended-spectrum triazole antifungals.

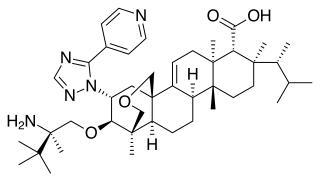

Ibrexafungerp, sold under the brand name Brexafemme, is an antifungal medication used to treat vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). It is taken orally. It is also currently undergoing clinical trials for other indications via an intravenous (IV) formulation. An estimated 75% of women will have at least one episode of VVC and 40 to 45% will have two or more episodes in their lifetime.

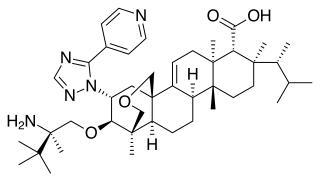

Oteseconazole, a novel orally bioavailable and selective inhibitor of fungal cytochrome P450 enzyme 51 (CYP51), has shown promising efficacy in the treatment of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) in patients.

TOL-463 is an anti-infective medication which is under development for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). It is a boric acid-based vaginal anti-infective enhanced with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) which was designed to have improved activity against vaginal bacterial and fungal biofilms while sparing protective lactobacilli. EDTA enhances the antimicrobial activity of boric acid and improves its efficacy against relevant biofilms. In a small phase 2 randomized controlled trial, TOL-463 as an insert or gel achieved clinical cure rates of 50–59% against BV and 81–92% against VVC in women who had one or both conditions. It was effective and safe in the study, though it was without indication of superiority over other antifungal medications for VVC. The cure rates against BV with TOL-463 were said to be comparable to those with recently approved antibiotic treatments like single-dose oral secnidazole (58%) and single-dose metronidazole vaginal gel (41%). As of May 2019, TOL-463 is in phase 2 clinical trials for the treatment of BV and VVC. It was originated by Toltec Pharmaceuticals and is under development by Toltec Pharmaceuticals and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.