Prince of Wales is a title traditionally given to the male heir apparent to the English and, later, British thrones. The title originated with the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd who, from the late 12th century, used it to assert their supremacy over the other Welsh rulers. However, to mark the finalisation of his conquest of Wales, in 1301, Edward I of England, invested his son Edward of Caernarfon with the title, thereby beginning the tradition of giving the title to the heir apparent when he was the monarch's son or grandson. The title was later claimed by the leader of a Welsh rebellion, Owain Glyndŵr, from 1400 until 1415.

The history of what is now Wales begins with evidence of a Neanderthal presence from at least 230,000 years ago, while Homo sapiens arrived by about 31,000 BC. However, continuous habitation by modern humans dates from the period after the end of the last ice age around 9000 BC, and Wales has many remains from the Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze Age. During the Iron Age the region, like all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth, the culture had become Celtic, with a common Brittonic language. The Romans, who began their conquest of Britain in AD 43, first campaigned in what is now northeast Wales in 48 against the Deceangli, and gained total control of the region with their defeat of the Ordovices in 79. The Romans departed from Britain in the 5th century, opening the door for the Anglo-Saxon settlement. Thereafter, the culture began to splinter into a number of kingdoms. The Welsh people formed with English encroachment that effectively separated them from the other surviving Brittonic-speaking peoples in the early middle ages.

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in 2021 of 3,107,500 and has a total area of 20,779 km2 (8,023 sq mi). Wales has over 1,680 miles (2,700 km) of coastline and is largely mountainous with its higher peaks in the north and central areas, including Snowdon, its highest summit. The country lies within the north temperate zone and has a changeable, maritime climate. The capital and largest city is Cardiff.

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was King of Wales from 1055 to 1063. He had previously been King of Gwynedd and Powys in 1039. He was the son of King Llywelyn ap Seisyll and Angharad daughter of Maredudd ab Owain, and the great-great-grandson of Hywel Dda.

The culture of Wales is distinct, with its own language, customs, politics, festivals, music and Art. Wales is primarily represented by the symbol of the red Welsh Dragon, but other national emblems include the leek and the daffodil.

England and Wales is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is English law.

The Kingdom of Gwynedd was a Welsh kingdom and a Roman Empire successor state that emerged in sub-Roman Britain in the 5th century during the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain.

The flag of Wales consists of a red dragon passant on a green and white field. As with many heraldic charges, the exact representation of the dragon is not standardised and many renderings exist. It is not represented in the Union Flag.

Welsh nationalism emphasises and celebrates the distinctiveness of Welsh culture and Wales as a nation or country. Welsh nationalism may also include calls for further autonomy or self determination which includes Welsh devolution, meaning increased powers for the Senedd, or full Welsh independence.

The Welsh Dragon is a heraldic symbol that represents Wales and appears on the national flag of Wales.

The Welsh are an ethnic group native to Wales. "Welsh people" applies to those who were born in Wales and to those who have Welsh ancestry, perceiving themselves or being perceived as sharing a cultural heritage and shared ancestral origins.

Welsh republicanism or republicanism in Wales is the political ideology of a Welsh republic, as opposed to Wales being presided over by the monarchy of the United Kingdom.

King of Wales was a rarely used title, because Wales, much like Ireland, rarely achieved a degree of political unity like that of England or Scotland during the Middle Ages. While many different leaders in Wales claimed the title of "King of Wales", the country was only truly united under the rule of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn as Prince of Wales from 1055 to 1063.

Wales in the Middle Ages covers the history of the country that is now called Wales, from the departure of the Romans in the early fifth century to the annexation of Wales into the Kingdom of England in the early sixteenth century. This period of about 1,000 years saw the development of regional Welsh kingdoms, Celtic conflict with the Anglo-Saxons, reducing Celtic territories, and conflict between the Welsh and the Anglo-Normans from the 11th century.

The cultural relationship between the Welsh and English manifests through many shared cultural elements including language, sport, religion and food. The cultural relationship is usually characterised by tolerance of people and cultures, although some mutual mistrust and racism or xenophobia persists. Hatred or fear of the Welsh by the English has been termed "Cymrophobia", and similar attitudes towards the English by the Welsh, or others, are termed "Anglophobia".

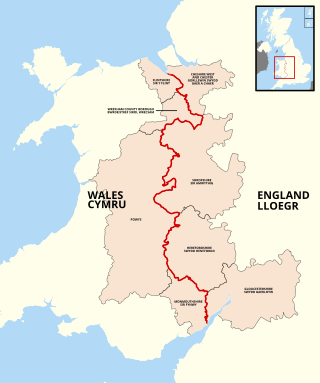

The England–Wales border, sometimes referred to as the Wales–England border or the Anglo-Welsh border, runs for 160 miles (260 km) from the Dee estuary, in the north, to the Severn estuary in the south, separating England and Wales.

The Royal House of Mathrafal began as a cadet branch of the Welsh Royal House of Dinefwr, taking their name from Mathrafal Castle, their principal seat and effective capital. They effectively replaced the House of Gwertherion, who had been ruling the Kingdom of Powys since late Roman Britain, through the politically advantageous marriage of an ancestor, Merfyn the Oppressor. His son, King Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, would join the resistance of the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, against the invasion of William the Conqueror, following the Norman conquest of England. Thereafter, they would struggle with the Plantagenets and the remaining Welsh Royal houses for the control of Wales. Although their fortunes rose and fell over the generations, they are primarily remembered as Kings of Powys and last native Prince of Wales.

The military history of Wales refers to military activity that has occurred in Wales or activity of a historic Welsh military or armed forces in Wales.