The history of Latvia began around 9000 BC with the end of the last glacial period in northern Europe. Ancient Baltic peoples arrived in the area during the second millennium BC, and four distinct tribal realms in Latvia's territory were identifiable towards the end of the first millennium AD. Latvia's principal river Daugava, was at the head of an important trade route from the Baltic region through Russia into southern Europe and the Middle East that was used by the Vikings and later Nordic and German traders.

Baltic Germans are ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their resettlement in 1945 after the end of World War II, Baltic Germans have markedly declined as a geographically determined ethnic group in the region.

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, these rights are institutionalized or supported by law, local custom, and behavior, whereas in others, they are ignored and suppressed. They differ from broader notions of human rights through claims of an inherent historical and traditional bias against the exercise of rights by women and girls, in favor of men and boys.

Gender equality, also known as sexual equality or equality of the sexes, is the state of equal ease of access to resources and opportunities regardless of gender, including economic participation and decision-making; and the state of valuing different behaviors, aspirations and needs equally, regardless of gender.

The Constitution of Latvia is the fundamental law of the Republic of Latvia. Satversme is the oldest Eastern or Central European constitution still in force and the sixth oldest still-functioning republican basic law in the world. It was adopted, as it states itself in the text, by the people of Latvia, as represented in the Constitutional Assembly of Latvia, on 15 February 1922 and came into force on 7 November 1922. It was heavily influenced by Germany's Weimar Constitution and the Swiss Federal Constitution. The constitution establishes the main bodies of government ; it consists of 116 articles arranged in eight chapters.

The Declaration "On the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia" was adopted on 4 May 1990 by the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR in which Latvia declared independence from the Soviet Union. The Declaration stated that, although Latvia had de facto lost its independence in 1940, when it was annexed by the Soviet Union, the country had de jure remained a sovereign country as the annexation had been unconstitutional and against the will of the Latvian people.

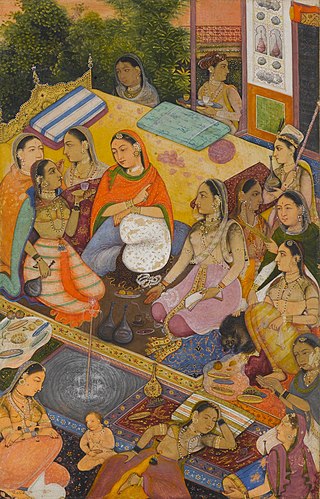

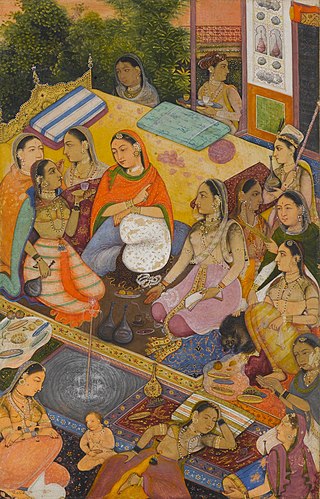

The study of women and religion examines women in the context of different religious faiths. This includes considering female gender roles in religious history as well as how women participate in religion. Particular consideration is given to how religion has been used as a patriarchal tool to elevate the status and power of men over women. In addition, religion portrays gender within religious doctrines.

Women in Kazakhstan are women who live in or are from Kazakhstan. Their position in society has been and is influenced by a variety of factors, including local traditions and customs, decades of Soviet regime, rapid social and economic changes and instability after independence, and new emerging Western values.

This page examines the dynamics surrounding women in Tajikistan.

Women in Uganda have substantial economic and social responsibilities throughout Uganda's many traditional societies. Ugandan women come from a range of economic and educational backgrounds. Despite economic and social progress throughout the country, domestic violence and sexual assault remain prevalent issues in Uganda. Illiteracy is directly correlated to increased level of domestic violence. This is mainly because household members can not make proper decisions that directly affect their future plans. Government reports suggest rising levels of domestic violence toward women that are directly attributable to poverty.

Women's history is the study of the role that women have played in history and the methods required to do so. It includes the study of the history of the growth of woman's rights throughout recorded history, personal achievements over a period of time, the examination of individual and groups of women of historical significance, and the effect that historical events have had on women. Inherent in the study of women's history is the belief that more traditional recordings of history have minimized or ignored the contributions of women to different fields and the effect that historical events had on women as a whole; in this respect, women's history is often a form of historical revisionism, seeking to challenge or expand the traditional historical consensus.

Women in Armenia have had equal rights, including the right to vote, since the establishment of the First Republic of Armenia. On June 21 and 23, 1919, the first direct parliamentary elections were held in Armenia under universal suffrage - every person over the age of 20 had the right to vote regardless of gender, ethnicity or religious beliefs. The 80-seat legislature, charged with setting the foundation for an Armenian state, contained three women deputies: Katarine Zalyan-Manukyan, Perchuhi Partizpanyan-Barseghyan and Varvara Sahakyan.

In Russia, feminism originated in the 18th century, influenced by the Age of Enlightenment in Western Europe and mostly confined to the aristocracy. Throughout the 19th century, the idea of feminism remained closely tied to revolutionary politics and to social reform. In the 20th century Russian feminists, inspired by socialist doctrine, shifted their focus from philanthropic works to labor organizing among peasants and factory workers. After the February Revolution of 1917, feminist lobbying gained suffrage, alongside general equality for women in society. Through this period, the concern with feminism varied depending on demographics and economic status.

The character of Polish women is shaped by Poland's history, culture, and politics. Poland has a long history of feminist activism, and was one of the first nations in Europe to enact women's suffrage. It is also strongly influenced by the conservative social views of the Catholic Church.

Women in Bulgaria refers to women who live in and are from Bulgaria. Women's position in Bulgarian society has been influenced by a variety of cultures and ideologies, including the Byzantine and Ottoman cultures, Eastern Orthodox Christianity, communist ideology, and contemporary globalized Western values.

The evolution and history of European women coincide with the evolution and the history of Europe itself. According to the Catalyst, 51.2% of the population of the European Union in 2010 is composed of women.

The culture, evolution, and history of women who were born in, live in, and are from the continent of Africa reflect the evolution and history of the African continent itself.

The evolution and history of women in Asia coincide with the evolution and history of Asian continent itself. They also correspond with the cultures that developed within the region. Asian women can be categorically grouped as women from the Asian subregions of Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Western Asia.

Feminism in Sweden is a significant social and political influence within Swedish society. Swedish political parties across the political spectrum commit to gender-based policies in their public political manifestos. The Swedish government assesses all policy according to the tenets of gender mainstreaming. Women in Sweden are 45% of the political representatives in the Swedish Parliament. Women make up 43% of representatives in local legislatures as of 2014. In addition, in 2014, newly sworn in Foreign Minister Margot Wallström announced a feminist foreign policy.

Berta Pīpiņa was a Latvian teacher, journalist, politician and women's rights activist. She was the first woman elected to serve in the Saeima although there was six female members Constitutional Assembly of Latvia from May 1, 1920, until November 7, 1922, when the 1st Saeima convened. Active in women's rights, during her time in the Riga City Council and the Saeima, she strove to enact laws and policies to promote women's equality and protect families. When Soviet troops occupied Latvia, she was deported to Siberia, her life was removed from encyclopedias, and she died in a gulag.