The peritoneum is the serous membrane forming the lining of the abdominal cavity or coelom in amniotes and some invertebrates, such as annelids. It covers most of the intra-abdominal organs, and is composed of a layer of mesothelium supported by a thin layer of connective tissue. This peritoneal lining of the cavity supports many of the abdominal organs and serves as a conduit for their blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves.

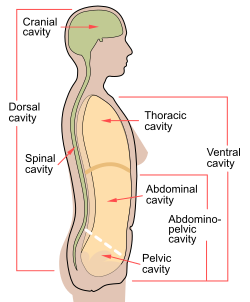

A body cavity is any space or compartment, or potential space, in an animal body. Cavities accommodate organs and other structures; cavities as potential spaces contain fluid.

Peritonitis is inflammation of the localized or generalized peritoneum, the lining of the inner wall of the abdomen and cover of the abdominal organs. Symptoms may include severe pain, swelling of the abdomen, fever, or weight loss. One part or the entire abdomen may be tender. Complications may include shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

In a multicellular organism, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a function. Tissues of different types combine to form an organ which has a specific function. The intestinal wall for example is formed by epithelial tissue and smooth muscle tissue. Two or more organs working together in the execution of a specific body function form an organ system, also called a biological system or body system.

The mesothelium is a membrane composed of simple squamous epithelial cells of mesodermal origin, which forms the lining of several body cavities: the pleura, peritoneum and pericardium.

The mesentery is an organ that attaches the intestines to the posterior abdominal wall and is formed by the double fold of peritoneum. It helps in storing fat and allowing blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves to supply the intestines, among other functions.

The peritoneal cavity is a potential space between the parietal peritoneum and visceral peritoneum. The parietal and visceral peritonea are layers of the peritoneum named depending on their function/location. It is one of the spaces derived from the coelomic cavity of the embryo, the others being the pleural cavities around the lungs and the pericardial cavity around the heart.

The serous membrane is a smooth tissue membrane of mesothelium lining the contents and inner walls of body cavities, which secrete serous fluid to allow lubricated sliding movements between opposing surfaces. The serous membrane that covers internal organs is called a visceral membrane; while the one that covers the cavity wall is called the parietal membrane. Between the two opposing serosal surfaces is often a potential space, mostly empty except for the small amount of serous fluid.

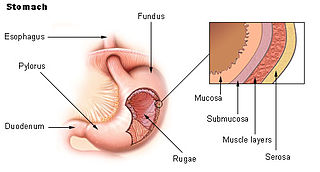

The lesser omentum is the double layer of peritoneum that extends from the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach, and to the first part of the duodenum. The lesser omentum is usually divided into these two connecting parts: the hepatogastric ligament, and the hepatoduodenal ligament.

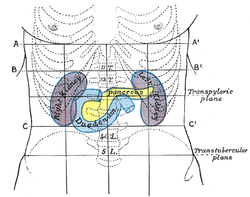

In the anatomy of humans and homologous primates, the ascending colon is the part of the colon located between the cecum and the transverse colon.

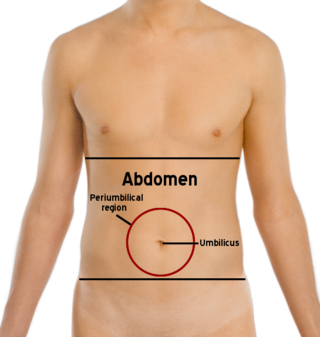

The abdomen is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the torso. The area occupied by the abdomen is called the abdominal cavity. In arthropods it is the posterior tagma of the body; it follows the thorax or cephalothorax.

The lesser sac, also known as the omental bursa, is a part of the peritoneal cavity that is formed by the lesser and greater omentum. Usually found in mammals, it is connected with the greater sac via the omental foramen or Foramen of Winslow. In mammals, it is common for the lesser sac to contain considerable amounts of fat.

In human anatomy, the transverse colon is the longest and most movable part of the colon.

The greater omentum is a large apron-like fold of visceral peritoneum that hangs down from the stomach. It extends from the greater curvature of the stomach, passing in front of the small intestines and doubles back to ascend to the transverse colon before reaching to the posterior abdominal wall. The greater omentum is larger than the lesser omentum, which hangs down from the liver to the lesser curvature. The common anatomical term "epiploic" derives from "epiploon", from the Greek epipleein, meaning to float or sail on, since the greater omentum appears to float on the surface of the intestines. It is the first structure observed when the abdominal cavity is opened anteriorly.

The paracolic gutters are peritoneal recesses – spaces between the colon and the abdominal wall.

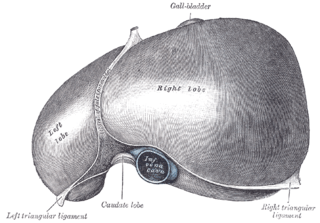

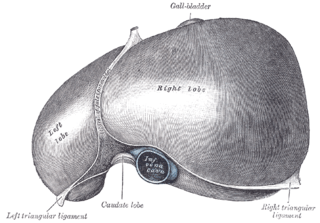

The left triangular ligament is a large peritoneal fold. It connects the posterior part of the upper surface of the left lobe of the liver to the thoracic diaphragm.

Peritoneal fluid is a serous fluid made by the peritoneum in the abdominal cavity which lubricates the surface of tissue that lines the abdominal wall and pelvic cavity. It covers most of the organs in the abdomen. An increased volume of peritoneal fluid is called ascites.

Peritoneal recesses are the spaces formed by peritoneum draping over viscera.

Peritoneal ligaments are folds of peritoneum that are used to connect viscera to viscera or the abdominal wall.

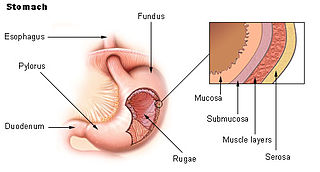

The development of the digestive system in the human embryo concerns the epithelium of the digestive system and the parenchyma of its derivatives, which originate from the endoderm. Connective tissue, muscular components, and peritoneal components originate in the mesoderm. Different regions of the gut tube such as the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, etc. are specified by a retinoic acid gradient that causes transcription factors unique to each region to be expressed. Differentiation of the gut and its derivatives depends upon reciprocal interactions between the gut endoderm and its surrounding mesoderm. Hox genes in the mesoderm are induced by a Hedgehog signaling pathway secreted by gut endoderm and regulate the craniocaudal organization of the gut and its derivatives. The gut system extends from the oropharyngeal membrane to the cloacal membrane and is divided into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut.