The peritoneum is the serous membrane forming the lining of the abdominal cavity or coelom in amniotes and some invertebrates, such as annelids. It covers most of the intra-abdominal organs, and is composed of a layer of mesothelium supported by a thin layer of connective tissue. This peritoneal lining of the cavity supports many of the abdominal organs and serves as a conduit for their blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves.

Peptic ulcer disease is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines is a duodenal ulcer. The most common symptoms of a duodenal ulcer are waking at night with upper abdominal pain, and upper abdominal pain that improves with eating. With a gastric ulcer, the pain may worsen with eating. The pain is often described as a burning or dull ache. Other symptoms include belching, vomiting, weight loss, or poor appetite. About a third of older people with peptic ulcers have no symptoms. Complications may include bleeding, perforation, and blockage of the stomach. Bleeding occurs in as many as 15% of cases.

The abdominal cavity is a large body cavity in humans and many other animals that contain organs. It is a part of the abdominopelvic cavity. It is located below the thoracic cavity, and above the pelvic cavity. Its dome-shaped roof is the thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle under the lungs, and its floor is the pelvic inlet, opening into the pelvis.

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a ruptured appendix include widespread, painful inflammation of the inner lining of the abdominal wall and sepsis.

Cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder. Symptoms include right upper abdominal pain, pain in the right shoulder, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally fever. Often gallbladder attacks precede acute cholecystitis. The pain lasts longer in cholecystitis than in a typical gallbladder attack. Without appropriate treatment, recurrent episodes of cholecystitis are common. Complications of acute cholecystitis include gallstone pancreatitis, common bile duct stones, or inflammation of the common bile duct.

Diverticulitis, also called colonic diverticulitis, is a gastrointestinal disease characterized by inflammation of abnormal pouches—diverticula—that can develop in the wall of the large intestine. Symptoms typically include lower abdominal pain of sudden onset, but the onset may also occur over a few days. There may also be nausea, diarrhea or constipation. Fever or blood in the stool suggests a complication. People may experience a single attack, repeated attacks, or ongoing "smouldering" diverticulitis.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a type of dialysis that uses the peritoneum in a person's abdomen as the membrane through which fluid and dissolved substances are exchanged with the blood. It is used to remove excess fluid, correct electrolyte problems, and remove toxins in those with kidney failure. Peritoneal dialysis has better outcomes than hemodialysis during the first couple of years. Other benefits include greater flexibility and better tolerability in those with significant heart disease.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is the development of a bacterial infection in the peritoneum, despite the absence of an obvious source for the infection. It is specifically an infection of the ascitic fluid – an increased volume of peritoneal fluid. Ascites is most commonly a complication of cirrhosis of the liver. It can also occur in patients with nephrotic syndrome. SBP has a high mortality rate.

Colic in horses is defined as abdominal pain, but it is a clinical symptom rather than a diagnosis. The term colic can encompass all forms of gastrointestinal conditions which cause pain as well as other causes of abdominal pain not involving the gastrointestinal tract. What makes it tricky is that different causes can manifest with similar signs of distress in the animal. Recognizing and understanding these signs is pivotal, as timely action can spell the difference between a brief moment of discomfort and a life-threatening situation. The most common forms of colic are gastrointestinal in nature and are most often related to colonic disturbance. There are a variety of different causes of colic, some of which can prove fatal without surgical intervention. Colic surgery is usually an expensive procedure as it is major abdominal surgery, often with intensive aftercare. Among domesticated horses, colic is the leading cause of premature death. The incidence of colic in the general horse population has been estimated between 4 and 10 percent over the course of the average lifespan. Clinical signs of colic generally require treatment by a veterinarian. The conditions that cause colic can become life-threatening in a short period of time.

Gastrointestinal perforation, also known as gastrointestinal rupture, is a hole in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. The gastrointestinal tract is composed of hollow digestive organs leading from the mouth to the anus. Symptoms of gastrointestinal perforation commonly include severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Complications include a painful inflammation of the inner lining of the abdominal wall and sepsis.

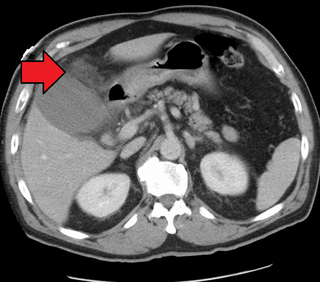

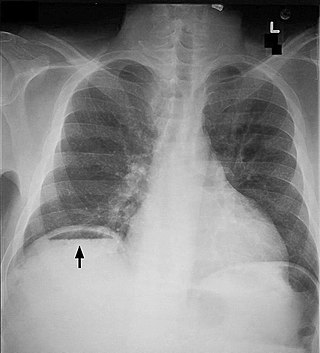

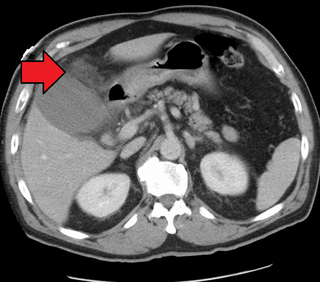

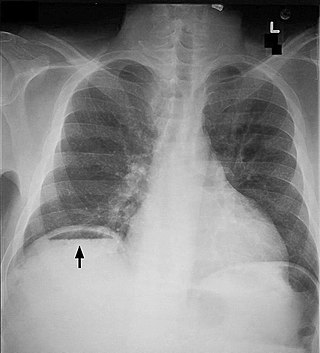

Pneumoperitoneum is pneumatosis in the peritoneal cavity, a potential space within the abdominal cavity. The most common cause is a perforated abdominal organ, generally from a perforated peptic ulcer, although any part of the bowel may perforate from a benign ulcer, tumor or abdominal trauma. A perforated appendix seldom causes a pneumoperitoneum.

Abdominal distension occurs when substances, such as air (gas) or fluid, accumulate in the abdomen causing its expansion. It is typically a symptom of an underlying disease or dysfunction in the body, rather than an illness in its own right. People with this condition often describe it as "feeling bloated". Affected people often experience a sensation of fullness, abdominal pressure, and sometimes nausea, pain, or cramping. In the most extreme cases, upward pressure on the diaphragm and lungs can also cause shortness of breath. Through a variety of causes, bloating is most commonly due to buildup of gas in the stomach, small intestine, or colon. The pressure sensation is often relieved, or at least lessened, by belching or flatulence. Medications that settle gas in the stomach and intestines are also commonly used to treat the discomfort and lessen the abdominal distension.

Valentino's syndrome is pain presenting in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen caused by a duodenal ulcer with perforation through the retroperitoneum.

An acute abdomen refers to a sudden, severe abdominal pain. It is in many cases a medical emergency, requiring urgent and specific diagnosis. Several causes need immediate surgical treatment.

A bowel resection or enterectomy is a surgical procedure in which a part of an intestine (bowel) is removed, from either the small intestine or large intestine. Often the word enterectomy is reserved for the sense of small bowel resection, in distinction from colectomy, which covers the sense of large bowel resection. Bowel resection may be performed to treat gastrointestinal cancer, bowel ischemia, necrosis, or obstruction due to scar tissue, volvulus, and hernias. Some patients require ileostomy or colostomy after this procedure as alternative means of excretion. Complications of the procedure may include anastomotic leak or dehiscence, hernias, or adhesions causing partial or complete bowel obstruction. Depending on which part and how much of the intestines are removed, there may be digestive and metabolic challenges afterward, such as short bowel syndrome.

Stercoral ulcer is an ulcer of the colon due to pressure and irritation resulting from severe, prolonged constipation due to a large bowel obstruction, damage to the autonomic nervous system, or stercoral colitis. It is most commonly located in the sigmoid colon and rectum. Prolonged constipation leads to production of fecaliths, leading to possible progression into a fecaloma. These hard lumps irritate the rectum and lead to the formation of these ulcers. It results in fresh bleeding per rectum. These ulcers may be seen on imaging, such as a CT scan but are more commonly identified using endoscopy, usually a colonoscopy. Treatment modalities can include both surgical and non-surgical techniques.

Abdominal guarding is the tensing of the abdominal wall muscles to guard inflamed organs within the abdomen from the pain of pressure upon them. The tensing is detected when the abdominal wall is pressed. Abdominal guarding is also known as 'défense musculaire'.

Abdominal trauma is an injury to the abdomen. Signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, tenderness, rigidity, and bruising of the external abdomen. Complications may include blood loss and infection.

Tertiary peritonitis is the inflammation of the peritoneum which persists for 48 hours after a surgery that has been successfully carried out in adequate surgical conditions. Tertiary peritonitis is usually the most delayed and severe consequence of nosocomial intra-abdominal infection. Patients who acquire tertiary peritonitis are usually admitted to ICU due to the critical, life-threatening nature of the condition which can lead to multi-organ failure despite treatment and has a high mortality rate of 60%. Signs and symptoms of tertiary peritonitis include fever, hypotension and abdominal pain. Diagnosis of the condition is often difficult and treatment intervention should be as early as possible.

Abdominal tuberculosis is a type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis which involves the abdominal organs such as intestines, peritoneum and abdominal lymph nodes. It can either occur in isolation or along with a primary focus in patients with disseminated tuberculosis.