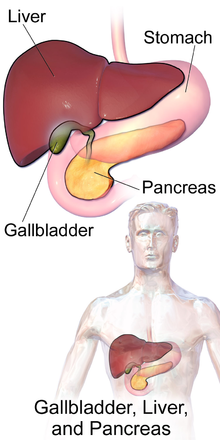

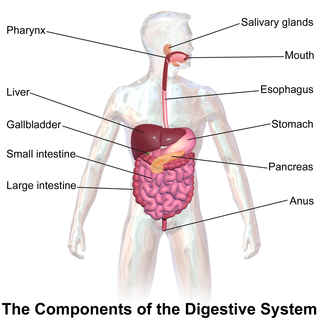

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although the structure and position of the gallbladder can vary significantly among animal species. It receives bile, produced by the liver, via the common hepatic duct, and stores it. The bile is then released via the common bile duct into the duodenum, where the bile helps in the digestion of fats.

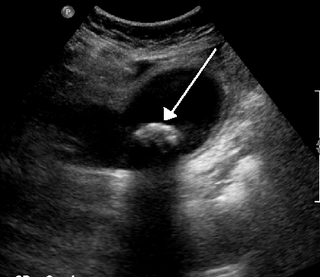

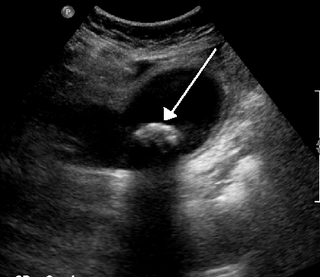

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of migrated gallstones within bile ducts.

Cholecystectomy is the surgical removal of the gallbladder. Cholecystectomy is a common treatment of symptomatic gallstones and other gallbladder conditions. In 2011, cholecystectomy was the eighth most common operating room procedure performed in hospitals in the United States. Cholecystectomy can be performed either laparoscopically, or via an open surgical technique.

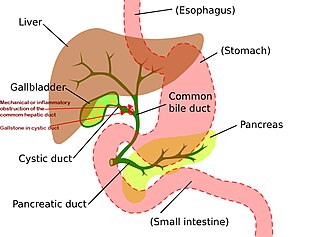

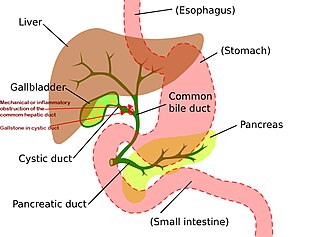

Mirizzi's syndrome is a rare complication in which a gallstone becomes impacted in the cystic duct or neck of the gallbladder causing compression of the common hepatic duct, resulting in obstruction and jaundice. The obstructive jaundice can be caused by direct extrinsic compression by the stone or from fibrosis caused by chronic cholecystitis (inflammation). A cholecystocholedochal fistula can occur.

Courvoisier's principle states that a painless palpably enlarged gallbladder accompanied with mild jaundice is unlikely to be caused by gallstones. Usually, the term is used to describe the physical examination finding of the right-upper quadrant of the abdomen. This sign implicates possible malignancy of the gallbladder or pancreas and the swelling is unlikely due to gallstones.

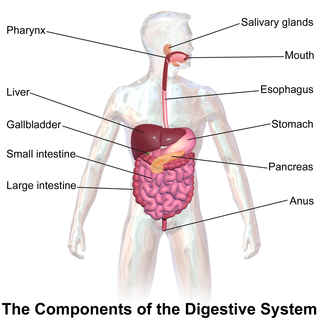

Gastrointestinal diseases refer to diseases involving the gastrointestinal tract, namely the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum, and the accessory organs of digestion, the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas.

Common bile duct stone, also known as choledocholithiasis, is the presence of gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD). This condition can cause jaundice and liver cell damage. Treatments include choledocholithotomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Gallbladder cancer is a relatively uncommon cancer, with an incidence of fewer than 2 cases per 100,000 people per year in the United States. It is particularly common in central and South America, central and eastern Europe, Japan and northern India; it is also common in certain ethnic groups e.g. Native American Indians and Hispanics. If it is diagnosed early enough, it can be cured by removing the gallbladder, part of the liver and associated lymph nodes. Most often it is found after symptoms such as abdominal pain, jaundice and vomiting occur, and it has spread to other organs such as the liver.

Adenomyoma is a tumor (-oma) including components derived from glands (adeno-) and muscle (-my-). It is a type of complex and mixed tumor, and several variants have been described in the medical literature. Uterine adenomyoma, the localized form of uterine adenomyosis, is a tumor composed of endometrial gland tissue and smooth muscle in the myometrium. Adenomyomas containing endometrial glands are also found outside of the uterus, most commonly on the uterine adnexa but can also develop at distant sites outside of the pelvis. Gallbladder adenomyoma, the localized form of adenomyomatosis, is a polypoid tumor in the gallbladder composed of hyperplastic mucosal epithelium and muscularis propria.

Ascending cholangitis, also known as acute cholangitis or simply cholangitis, is inflammation of the bile duct, usually caused by bacteria ascending from its junction with the duodenum. It tends to occur if the bile duct is already partially obstructed by gallstones.

Biliary colic, also known as symptomatic cholelithiasis, a gallbladder attack or gallstone attack, is when a colic occurs due to a gallstone temporarily blocking the cystic duct. Typically, the pain is in the right upper part of the abdomen, and can be severe. Pain usually lasts from 15 minutes to a few hours. Often, it occurs after eating a heavy meal, or during the night. Repeated attacks are common. Cholecystokinin - a gastrointestinal hormone - plays a role in the colic, as following the consumption of fatty meals, the hormone triggers the gallbladder to contract, which may expel stones into the duct and temporarily block it until being successfully passed.

The biliary tract refers to the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts, and how they work together to make, store and secrete bile. Bile consists of water, electrolytes, bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and conjugated bilirubin. Some components are synthesized by hepatocytes ; the rest are extracted from the blood by the liver.

Gallbladder diseases are diseases involving the gallbladder and is closely linked to biliary disease, with the most common cause being gallstones (cholelithiasis).

Gallbladder polyps are growths or lesions resembling growths in the wall of the gallbladder. True polyps are abnormal accumulations of mucous membrane tissue that would normally be shed by the body.

Biliary dyskinesia is a disorder of some component of biliary part of the digestive system in which bile cannot physically move in the proper direction through the tubular biliary tract. It most commonly involves abnormal biliary tract peristalsis muscular coordination within the gallbladder in response to dietary stimulation of that organ to squirt the liquid bile through the common bile duct into the duodenum. Ineffective peristaltic contraction of that structure produces postprandial right upper abdominal pain (cholecystodynia) and almost no other problem. When the dyskinesia is localized at the biliary outlet into the duodenum just as increased tonus of that outlet sphincter of Oddi, the backed-up bile can cause pancreatic injury with abdominal pain more toward the upper left side. In general, biliary dyskinesia is the disturbance in the coordination of peristaltic contraction of the biliary ducts, and/or reduction in the speed of emptying of the biliary tree into the duodenum.

Biliary injury is the traumatic damage of the bile ducts. It is most commonly an iatrogenic complication of cholecystectomy, but can also be caused by other operations or by major trauma. The risk of biliary injury is higher during laparoscopic cholecystectomy than during open cholecystectomy. Biliary injury may lead to several complications and may even cause death if not diagnosed in time and managed properly. Ideally biliary injury should be managed at a center with facilities and expertise in endoscopy, radiology and surgery.

Biliary sludge refers to a viscous mixture of small particles derived from bile. These sediments consist of cholesterol crystals, calcium salts, calcium bilirubinate, mucin, and other materials.

A biloma is a circumscribed abdominal collection of bile outside the biliary tree. It occurs when there is excess bile in the abdominal cavity. It can occur during or after a bile leak. There is an increased chance of a person developing biloma after having a gallbladder removal surgery, known as laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This procedure can be complicated by biloma with incidence of 0.3–2%. Other causes are liver biopsy, abdominal trauma, and, rarely, spontaneous perforation. The formation of biloma does not occur frequently. Biliary fistulas are also caused by injury to the bile duct and can result in the formation of bile leaks. Biliary fistulas are abnormal communications between organs and the biliary tract. Once diagnosed, they usually require drainage. The term "biloma" was first coined in 1979 by Gould and Patel. They discovered it in a case with extrahepatic bile leakage. The cause of this was trauma to the upper right quadrant of the abdomen. Originally, biloma was described as an "encapsulated collection" of extrahepatic bile. Biloma is now described as extrabiliary collections of bile that can be either intrahepatic or extrahepatic. The most common cause of biloma is trauma to the liver. There are other causes such as abdominal surgery, endoscopic surgery and percutaneous catheter drainage. Injury and abdominal trauma can cause damage to the biliary tree. The biliary tree is a system of vessels that direct secreations from the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas through a series of ducts into the duodenum. This can result in a bile leak which is a common cause of the formation of biloma. It is possible for biloma to be associated with mortality, though it is not common. Bile leaks occur in about one percent of causes.

Canine gallbladder mucocele (GBM) is an emerging biliary disease in dogs described as the excessive and abnormal accumulation of thick, gelatinous mucus in the lumen, which results in an enlarged gallbladder. GBMs have been diagnosed more frequently in comparison to prior to the 2000s when it was considered rare. The mucus is usually pale yellow to dark green in appearance.

Choledochoduodenostomy (CDD) is a surgical procedure to create an anastomosis, a surgical connection, between the common bile duct (CBD) and an alternative portion of the duodenum. In healthy individuals, the CBD meets the pancreatic duct at the ampulla of Vater, which drains via the major duodenal papilla to the second part of duodenum. In cases of benign conditions such as narrowing of the distal CBD or recurrent CBD stones, performing a CDD provides the diseased patient with CBD drainage and decompression. A side-to-side anastomosis is usually performed.