Crohn's disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms often include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, abdominal distension, and weight loss. Complications outside of the gastrointestinal tract may include anemia, skin rashes, arthritis, inflammation of the eye, and fatigue. The skin rashes may be due to infections as well as pyoderma gangrenosum or erythema nodosum. Bowel obstruction may occur as a complication of chronic inflammation, and those with the disease are at greater risk of colon cancer and small bowel cancer.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of the two types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with the other type being Crohn's disease. It is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum. The primary symptoms of active disease are abdominal pain and diarrhea mixed with blood (hematochezia). Weight loss, fever, and anemia may also occur. Often, symptoms come on slowly and can range from mild to severe. Symptoms typically occur intermittently with periods of no symptoms between flares. Complications may include abnormal dilation of the colon (megacolon), inflammation of the eye, joints, or liver, and colon cancer.

Defecation follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus or cloaca. The act has a variety of names ranging from the common, like pooping or crapping, to the technical, e.g. bowel movement, to the obscene (shitting), to the euphemistic, to the juvenile. The topic, usually avoided in polite company, can become the basis for some potty humor.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory conditions of the colon and small intestine, with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (UC) being the principal types. Crohn's disease affects the small intestine and large intestine, as well as the mouth, esophagus, stomach and the anus, whereas UC primarily affects the colon and the rectum.

Colitis is swelling or inflammation of the large intestine (colon). Colitis may be acute and self-limited or long-term. It broadly fits into the category of digestive diseases.

Toxic megacolon is an acute form of colonic distension. It is characterized by a very dilated colon (megacolon), accompanied by abdominal distension (bloating), and sometimes fever, abdominal pain, or shock.

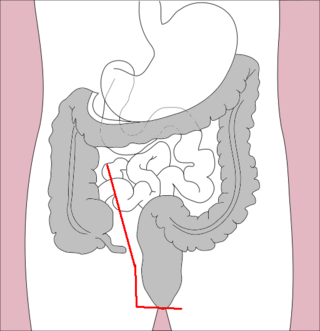

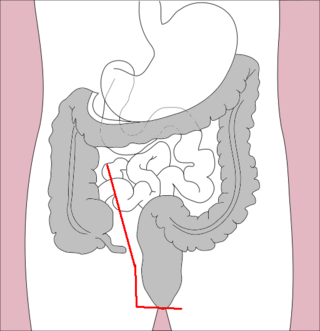

In medicine, the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA), also known as restorative proctocolectomy (RPC), ileal-anal reservoir (IAR), an ileo-anal pouch, ileal-anal pullthrough, or sometimes referred to as a J-pouch, S-pouch, W-pouch, or a pelvic pouch, is an anastomosis of a reservoir pouch made from ileum to the anus, bypassing the former site of the colon in cases where the colon and rectum have been removed. The pouch retains and restores functionality of the anus, with stools passed under voluntary control of the person, preventing fecal incontinence and serving as an alternative to a total proctocolectomy with ileostomy.

Colectomy is bowel resection of the large bowel. It consists of the surgical removal of any extent of the colon, usually segmental resection. In extreme cases where the entire large intestine is removed, it is called total colectomy, and proctocolectomy denotes that the rectum is included.

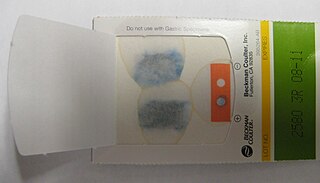

Blood in stool or rectal bleeding looks different depending on how early it enters the digestive tract—and thus how much digestive action it has been exposed to—and how much there is. The term can refer either to melena, with a black appearance, typically originating from upper gastrointestinal bleeding; or to hematochezia, with a red color, typically originating from lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Evaluation of the blood found in stool depends on its characteristics, in terms of color, quantity and other features, which can point to its source, however, more serious conditions can present with a mixed picture, or with the form of bleeding that is found in another section of the tract. The term "blood in stool" is usually only used to describe visible blood, and not fecal occult blood, which is found only after physical examination and chemical laboratory testing.

Pouchitis is an umbrella term for inflammation of the ileal pouch, an artificial rectum surgically created out of ileum in patients who have undergone a proctocolectomy or total colectomy. The ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is created in the management of patients with ulcerative colitis, indeterminate colitis, familial adenomatous polyposis, cancer, or rarely, other colitides.

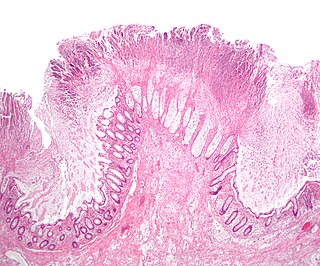

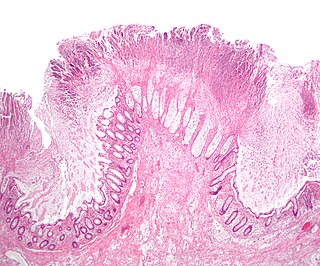

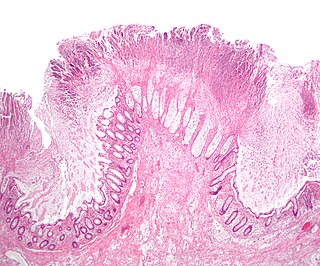

Microscopic colitis refers to two related medical conditions which cause diarrhea: collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis. Both conditions are characterized by the presence of chronic non-bloody watery diarrhea, normal appearances on colonoscopy and characteristic histopathology findings of inflammatory cells.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, commonly abbreviated LGIB, is any form of gastrointestinal bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract. LGIB is a common reason for seeking medical attention at a hospital's emergency department. LGIB accounts for 30–40% of all gastrointestinal bleeding and is less common than upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). It is estimated that UGIB accounts for 100–200 per 100,000 cases versus 20–27 per 100,000 cases for LGIB. Approximately 85% of lower gastrointestinal bleeding involves the colon, 10% are from bleeds that are actually upper gastrointestinal bleeds, and 3–5% involve the small intestine.

In the anatomy of humans and homologous primates, the descending colon is the part of the colon extending from the left colic flexure to the level of the iliac crest. The function of the descending colon in the digestive system is to store the remains of digested food that will be emptied into the rectum.

Proctocolectomy is the surgical removal of the entire colon and rectum from the human body, leaving the patients small intestine disconnected from their anus. It is a major surgery that is performed by colorectal surgeons, however some portions of the surgery, specifically the colectomy may be performed by general surgeons. It was first performed in 1978 and since that time, medical advancements have led to the surgery being less invasive with great improvements in patient outcomes. The procedure is most commonly indicated for severe forms of inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. It is also the treatment of choice for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis.

Biological therapy, the use of medications called biopharmaceuticals or biologics that are tailored to specifically target an immune or genetic mediator of disease, plays a major role in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Even for diseases of unknown cause, molecules that are involved in the disease process have been identified, and can be targeted for biological therapy. Many of these molecules, which are mainly cytokines, are directly involved in the immune system. Biological therapy has found a niche in the management of cancer, autoimmune diseases, and diseases of unknown cause that result in symptoms due to immune related mechanisms.

Lymphocytic colitis is a subtype of microscopic colitis, a condition characterized by chronic non-bloody watery diarrhea.

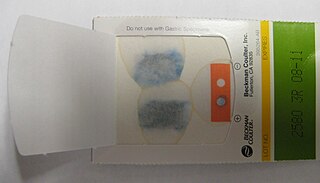

Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCAs) are antibodies against antigens presented by the cell wall of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. These antibodies are directed against oligomannose sequences α-1,3 Man n. ASCAs and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCAs) are the two most useful and often discriminating biomarkers for colitis. ASCA tends to recognize Crohn's disease more frequently, whereas pANCA tend to recognize ulcerative colitis.

Pancolitis or universal colitis, in its most general sense, refers to inflammation of the entire large intestine comprising the cecum, ascending, transverse, descending, sigmoid colon and rectum. It can be caused by a variety of things such as inflammatory bowel disease, more specifically a severe form of ulcerative colitis. A diagnosis can be made using a number of techniques but the most accurate method is direct visualization via a colonoscopy. Symptoms are similar to those of ulcerative colitis but more severe and affect the entire large intestine. Patients generally exhibit symptoms including rectal bleeding as a result of ulcers, pain in the abdominal region, inflammation in varying degrees, and diarrhea, fatigue, fever, and night sweats. Due to the loss of function in the large intestine patients may lose large amounts of weight from being unable to procure nutrients from food. In other cases the blood loss from ulcers can result in anemia which can be treated with iron supplements. Additionally, due to the chronic nature of most cases of pancolitis, patients have a higher chance of developing colorectal cancer.

Colonic ulcer can occur at any age, in children however they are rare. Most common symptoms are abdominal pain and hematochezia.

Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD) is a condition characterized by localized inflammation in the colon, which spares the rectum and is associated with multiple sac-like protrusions or pouches in the wall of the colon (diverticulosis). Unlike diverticulitis, SCAD involves inflammation of the colon between diverticula, while sparing the diverticular orifices. SCAD may lead to abdominal pain, especially in the left lower quadrant, intermittent rectal bleeding and chronic diarrhea.