Pancreatitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas is a large organ behind the stomach that produces digestive enzymes and a number of hormones. There are two main types: acute pancreatitis, and chronic pancreatitis.

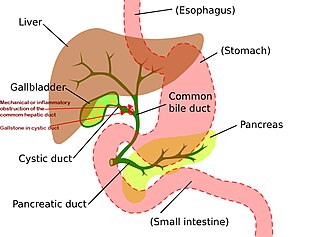

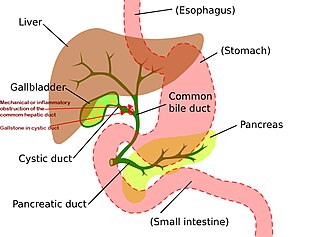

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although the structure and position of the gallbladder can vary significantly among animal species. It receives bile, produced by the liver, via the common hepatic duct, and stores it. The bile is then released via the common bile duct into the duodenum, where the bile helps in the digestion of fats.

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of migrated gallstones within bile ducts.

Cholecystitis is inflammation of the gallbladder. Symptoms include right upper abdominal pain, pain in the right shoulder, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally fever. Often gallbladder attacks precede acute cholecystitis. The pain lasts longer in cholecystitis than in a typical gallbladder attack. Without appropriate treatment, recurrent episodes of cholecystitis are common. Complications of acute cholecystitis include gallstone pancreatitis, common bile duct stones, or inflammation of the common bile duct.

Cholecystectomy is the surgical removal of the gallbladder. Cholecystectomy is a common treatment of symptomatic gallstones and other gallbladder conditions. In 2011, cholecystectomy was the eighth most common operating room procedure performed in hospitals in the United States. Cholecystectomy can be performed either laparoscopically, or via an open surgical technique.

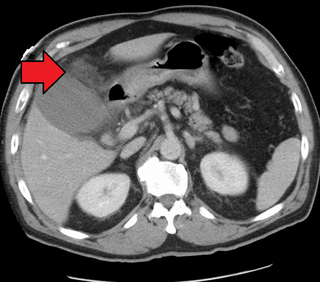

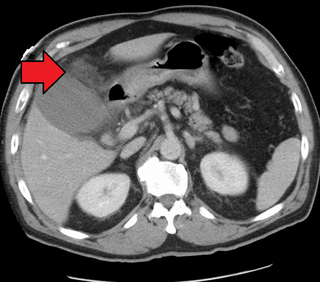

Mirizzi's syndrome is a rare complication in which a gallstone becomes impacted in the cystic duct or neck of the gallbladder causing compression of the common hepatic duct, resulting in obstruction and jaundice. The obstructive jaundice can be caused by direct extrinsic compression by the stone or from fibrosis caused by chronic cholecystitis (inflammation). A cholecystocholedochal fistula can occur.

Courvoisier's principle states that a painless palpably enlarged gallbladder accompanied with mild jaundice is unlikely to be caused by gallstones. Usually, the term is used to describe the physical examination finding of the right-upper quadrant of the abdomen. This sign implicates possible malignancy of the gallbladder or pancreas and the swelling is unlikely due to gallstones.

Common bile duct stone, also known as choledocholithiasis, is the presence of gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD). This condition can cause jaundice and liver cell damage. Treatments include choledocholithotomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Gallbladder cancer is a relatively uncommon cancer, with an incidence of fewer than 2 cases per 100,000 people per year in the United States. It is particularly common in central and South America, central and eastern Europe, Japan and northern India; it is also common in certain ethnic groups e.g. Native American Indians and Hispanics. If it is diagnosed early enough, it can be cured by removing the gallbladder, part of the liver and associated lymph nodes. Most often it is found after symptoms such as abdominal pain, jaundice and vomiting occur, and it has spread to other organs such as the liver.

Porcelain gallbladder is a calcification of the gallbladder believed to be brought on by excessive gallstones, although the exact cause is not clear. As with gallstone disease in general, this condition occurs mostly in overweight female patients of middle age. It is a morphological variant of chronic cholecystitis. Inflammatory scarring of the wall, combined with dystrophic calcification within the wall transforms the gallbladder into a porcelain-like vessel. Removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) is the recommended treatment.

Adenomyoma is a tumor (-oma) including components derived from glands (adeno-) and muscle (-my-). It is a type of complex and mixed tumor, and several variants have been described in the medical literature. Uterine adenomyoma, the localized form of uterine adenomyosis, is a tumor composed of endometrial gland tissue and smooth muscle in the myometrium. Adenomyomas containing endometrial glands are also found outside of the uterus, most commonly on the uterine adnexa but can also develop at distant sites outside of the pelvis. Gallbladder adenomyoma, the localized form of adenomyomatosis, is a polypoid tumor in the gallbladder composed of hyperplastic mucosal epithelium and muscularis propria.

Ascending cholangitis, also known as acute cholangitis or simply cholangitis, is inflammation of the bile duct, usually caused by bacteria ascending from its junction with the duodenum. It tends to occur if the bile duct is already partially obstructed by gallstones.

The biliary tract refers to the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts, and how they work together to make, store and secrete bile. Bile consists of water, electrolytes, bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and conjugated bilirubin. Some components are synthesized by hepatocytes ; the rest are extracted from the blood by the liver.

Gallbladder diseases are diseases involving the gallbladder and is closely linked to biliary disease, with the most common cause being gallstones (cholelithiasis).

Cholescintigraphy or hepatobiliary scintigraphy is scintigraphy of the hepatobiliary tract, including the gallbladder and bile ducts. The image produced by this type of medical imaging, called a cholescintigram, is also known by other names depending on which radiotracer is used, such as HIDA scan, PIPIDA scan, DISIDA scan, or BrIDA scan. Cholescintigraphic scanning is a nuclear medicine procedure to evaluate the health and function of the gallbladder and biliary system. A radioactive tracer is injected through any accessible vein and then allowed to circulate to the liver, where it is excreted into the bile ducts and stored by the gallbladder until released into the duodenum.

Biliary injury is the traumatic damage of the bile ducts. It is most commonly an iatrogenic complication of cholecystectomy, but can also be caused by other operations or by major trauma. The risk of biliary injury is higher during laparoscopic cholecystectomy than during open cholecystectomy. Biliary injury may lead to several complications and may even cause death if not diagnosed in time and managed properly. Ideally biliary injury should be managed at a center with facilities and expertise in endoscopy, radiology and surgery.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction refers to a group of functional disorders leading to abdominal pain due to dysfunction of the Sphincter of Oddi: functional biliary sphincter of Oddi and functional pancreatic sphincter of Oddi disorder. The sphincter of Oddi is a sphincter muscle, a circular band of muscle at the bottom of the biliary tree which controls the flow of pancreatic juices and bile into the second part of the duodenum. The pathogenesis of this condition is recognized to encompass stenosis or dyskinesia of the sphincter of Oddi ; consequently the terms biliary dyskinesia, papillary stenosis, and postcholecystectomy syndrome have all been used to describe this condition. Both stenosis and dyskinesia can obstruct flow through the sphincter of Oddi and can therefore cause retention of bile in the biliary tree and pancreatic juice in the pancreatic duct.

Cholecystostomy or (cholecystotomy) is a medical procedure used to drain the gallbladder through either a percutaneous or endoscopic approach. The procedure involves creating a stoma in the gallbladder, which can facilitate placement of a tube or stent for drainage, first performed by American surgeon, Dr. John Stough Bobbs, in 1867. It is sometimes used in cases of cholecystitis or other gallbladder disease where the person is ill, and there is a need to delay or defer cholecystectomy. The first endoscopic cholecystostomy was performed by Drs. Todd Baron and Mark Topazian in 2007 using ultrasound guidance to puncture the stomach wall and place a plastic biliary catheter for gallbladder drainage.

Biliary sludge refers to a viscous mixture of small particles derived from bile. These sediments consist of cholesterol crystals, calcium salts, calcium bilirubinate, mucin, and other materials.

Choledochoduodenostomy (CDD) is a surgical procedure to create an anastomosis, a surgical connection, between the common bile duct (CBD) and an alternative portion of the duodenum. In healthy individuals, the CBD meets the pancreatic duct at the ampulla of Vater, which drains via the major duodenal papilla to the second part of duodenum. In cases of benign conditions such as narrowing of the distal CBD or recurrent CBD stones, performing a CDD provides the diseased patient with CBD drainage and decompression. A side-to-side anastomosis is usually performed.